IN DENMARK

FORMERLY the terrors of a sea-voyage from Kiel deterred many travellers from thinking of a tour in Denmark or Sweden, but now a succession of railways makes everything easy, and while nothing can be imagined more invigorating or pleasant, there is probably no pleasure more economical than a summer in Scandinavia. Those who are worn with a London season will feel as if every breath in the crystal air of Denmark endued them with fresh health and strength, and then, after they have seen its old palaces and its beech woods and its Thorwaldsen sculptures, a voyage of ten minutes will carry them over the narrow Sound to the soft beauties of genial Sweden and the wild splendours of Norway.

Either Hamburg or Lübeck must be the starting-point for the overland route to Denmark, and the old free city of Lübeck, though quite a small place, is one of the most remarkable towns in Germany. We arrived there one hot summer afternoon, after a weary journey over the arid sandy plains which separate it from Berlin, and suddenly seemed to be transported into a land of verdure. Lilacs and roses bloomed everywhere; a wood lined the bank of the limpid river Trave, and in its waters - beyond the old wooden bridge - were reflected all the tallest steeples, often strangely out of the perpendicular, of many-towered Lübeck. A wonderful gate of red brick and golden-hued terracotta is the entrance from the station, and in the market-place are the quaintest turrets towers, tourelles, but all ending in spires. The lofty houses, so full of rich colour, throw cool shade on the streets on the hottest summer day; and we enjoyed a Sunday in the excellent hotel, with wooden galleries opening towards a splashing fountain in a quiet square, where a fat constable busied himself in keeping everybody from fulfilling any avocation whatever whilst service was being performed in the churches, but let them do exactly as they pleased as soon as it was over.

It must, at best, be a weary journey across West Holstein, through a succession of arid flats varied by stagnant swamps. We spent the weary hours in studying Dunham's 'History of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway,' which cannot be sufficiently recommended to all Scandinavian travellers. The glowing accounts in the English guide books of a lake and an old castle beguiled us into spending a night at Sleswig, but it turned out that the lake had disappeared before the memory of man, and that the castle was a white modern barrack. The colourless town and its long sleepy suburb, moored as if upon a raft in the marshes, straggle along the edge of a waveless fiord. At the end is the rugged cathedral like a barn, with a belfry like a dovecot, and inside it a curious altar-piece by Hans Brüggemann, pupil of Albert Dürer, and the noble monument of Frederick I., the first Lutheran King of Denmark; while richly carved doors at the sides of the church admit one to see how the grandmother of the Princess of Wales and various other potentates lie - Danish fashion - in gorgeous exposed coffins without any tombs at all. Everywhere roses grow in the streets, trained upon the house walls; and, up the pavement, crowds of the children were hurrying in the early morning, carrying in their hands the shoes they were going to wear when they were in school. In the evenings these children will not venture outside the town, for over the marshes they say that the wild huntsman rides, followed by his demon hounds and blowing his magic horn. It is the spirit of Duke Abel the fratricide, who, in the fens, murdered his brother Eric VI. of Denmark, and who was aftenvards lost there himself, falling from his horse, and being dragged down by the weight of his armour. To give rest to his wandering spirit, the clergy dug up his body and despatched it to Bremen, but there his vampire gave the canons no peace, so they sent the corpse back again, and now it lies once more in the marshes of Gottorp.

Most unutterably hideous is the country through which the railway now travels, wearisome levels only broken here and there by mounds, probably sepulchral. A straight line with tiny hillocks at intervals would do for a sketch of the whole of Sleswig and the greater part of Funen and Zealand. In times of early Danish history it was a frequent punishment to bury criminals alive in these dismal peat mosses. Twelve hours of changelessly flat scenery bring travellers from Hamburg to Frederikshaven, where we embark upon the Little Belt, the luggage-vans of the train being shunted on board the steamer. Immediately opposite lie the sandy shores of Funen, and in a few minutes we are there. Then four hours of ugly scenery take us across the island. It is only necessary to look out at the little town of Odense, called after the old hero-god, which was the birthplace of Hans Christian Andersen in 1805. The cathedral of Odense contains the shrine of the sainted King Canute IV. (1080-86), who was murdered while kneeling before the altar, owing to indignation at the severe taxation to which the love of Church endowment had incited him.

Nyborg, where we meet the sea again, will recall to lovers of old ballads the story of the innocent young knight Folker Lowmanson, and his cruel death here in a barrel of spikes, from the jealousy of Waldemar IV. for his beautiful queen Helwig, and how, to know his fate –

With anxious heart did Denmark's Queen

To Nyborg urge her horse,

And at the gate his bier she met,

And on it Folkers corse.

Such honour shown to son of knight

I never yet could hear.

The Queen of Denmark walked on foot

Herself before his bier.

In tears then Helwig mounted horse

And silent homeward rode,

For in her heart a life-long grief

Had taken its abode.

At Nyborg we embark on a miserable steamer for the passage of the Great Belt. It lasts an hour and a half and is often most wretched. On landing at Korsor travellers are hurried into the train which is waiting for the vessel.

Now the country improves a little. Here and there we pass through great beech woods. Down the green glades of one of them a glimpse is caught of the college of Sorö. It occupies the site of a monastery founded by Asker Ryg, a chieftain who, when he departed on a journey of warfare, vowed that if the child to which his wife, Inge, was about to give birth proved to be a girl, he would give his new building a spire, but a tower if it were a boy. On his return he saw two towers using in the distance. Inge had given birth to twin sons, who lived to become Asbiorn Snare, celebrated in the ballad of 'Fair Christal,' and Absalon, the warrior Bishop of Roeskilde - 'first captain by sea and land.' Absalon is buried here in the church of Sorci, which contains the tomb of King Olaf, the shortlived son of the famous Queen Margaret; of her cruel father, Waldemar Atterdag, whose last words expressed regret that he had not suffocated his daughter in her cradle; and of her grandfather, Christopher II., with his wife, Euphemia of Pomerania. Soon we pass Ringsted, which is scarcely worth stopping at, though its church contains the fine brass of King Erik Menred (1319) and his queen, Ingeborga, and though twenty kings and queens were entombed there before Roeskilde became the royal place of sepulture. Amongst them lies the popular Queen Dagmar, first wife of Waldemar II., still celebrated in ballad literature, for there is scarcely a Dane who is ignorant of the touching story of 'Queen Dagmar's Death,' which begins

Queen Dagmar is lying at Ribé sick,

At Ringsted is made her grave,

and which contains her last touching request to her husband, and her simple confession of the only 'sin' she could remember –

Had I on a Sunday not laced my sleeves

Or border upon them sewn,

No pangs had I felt by day or night,

Or torture of hell-fire known.

Tradition tells us that the dismal town of Ringsted was founded by King Ring, a warrior who, when he was seriously wounded in battle, placed the bodies of his slain heroes and that of his queen, Alpol, on board a ship laden with pitch, and going out to the open sea, set the vessel on fire, and then fell upon his sword.

In the twilight we pass Roeskilde, and at 10½ P.M. long rows of street lamps reflected in canals show that we have reached Copenhagen.

To those whose travels have chiefly led them southwards there is a great pleasure in the first awaking in Copenhagen. Everything is new – the associations, the characteristics, the history; even the very names on the omnibuses are suggestive of the sagas and romances of the North; and though the summer sun is hot, the atmosphere is as dear as that of a tramontana day in an Italian winter, and the air is indescribably elastic. The comfortable Hôtel d'Angleterre stands in the Kongens Nytorv, a modern square, with trees surrounding a statue in the centre, but there are glimpses of picturesque shipping down the side streets, and hard by is a spire quite ideally Danish, formed by three marvellous dragons with their tails twisted together in the air. Tradition declares that it was moved bodily from Calmar, in the south of Sweden. It rises now from a beautiful building of brick erected in 1624 by Christian IV., brother-in-law of James 1. of England, and used as the Exchange.

Not far off is the principal palace - Christiansborg Slot, often rebuilt, and very white and ugly. It was partially destroyed by fire in 1884. Besides the royal residence, its vast courts contain the Chambers of Parliament, the Royal Library, and a Picture Gallery chiefly filled with the works of native artists, amongst which those of Marstrand and Bloch are very striking and well worthy of attention.

THE DRAGON TOWER, COPENHAGEN.

A queer building in the shadow of the palace, which attracts notice by its frescoed walls, is the Thorwaldsen Museum, the shrine where Denmark has reverentially collected all the works and memorials of her greatest artist - Bertel Thonvaldsen. Though his family is said to have descended from the Danish king Harold Stildetand, he was born (in 1770) the son of one Gottschalk, who, half workman, half artist, was employed in carving figures for the bows of vessels. From his earliest childhood little Bertel accompanied his father to the wharfs and assisted him in his work, in which he showed such intelligence that in his eleventh year he was allowed to enter the Free School of Art. Here he soon made wonderful progress in sculpture, but could so little be persuaded to attend to other studies that he reached the age of eighteen scarcely able to read. In his twenty-third year he obtained the great gold medal, to which a travelling stipend is attached, and thus he was enabled to go to Rome, where, encouraged at first by the patronage of Thomas Hope, the English banker, he soon reached the highest pitch of celebrity. Denmark became proud of her son, so that his visits to his native town in 1819 and 1837 were like triumphal progresses, all the city going forth to meet him, and lodging him splendidly at the public cost; but his heart always clung to the Eternal City, which continued to be the scene of his labours. Of his many works perhaps his noble lion at Lucerne is the best known. He never married, though he was long attached to a member of the old Scottish house of Mackenzie, and he died on a visit to Copenhagen in 1844.

In accordance with Thorwaldsen's own wish, he rests in the centre of his works. His grave has no tombstone, but is covered with green ivy. All around the little court which contains it are halls and galleries filled with the marvellously varied productions of his genius, arranged in the order of their execution - casts of all his absent sculptures and many most grand originals. Especially beautiful are the statue of Mercury, modelled from a Roman boy, of which the original is in the possessron of Lord Ashburton, and the exquisite reliefs of the Ages of Love, and of Day and Night, the two latter resulting from the inspiration of a single afternoon. But all seem to culminate in the great Hall of Christ, for though the statues here are only cast from those in the Vor Frue Kirche, they are far better seen in the well-lighted chamber than in the church. The colossal figures of the apostles lead up to the Saviour in sublime benediction; perhaps the statues of Simon Zelotes and the pilgrim S. James are the noblest amongst them. In the last room are gathered all the little personal memorials of Thorwaldsen - his books, pictures, and furniture.

The Museum of Northern Antiquities should also be visited and the Tower of the Trinity Church, with a roadway inside making an easy ascent to the strange view of many roofs and many waters which is obtained from the top. But the most delightful place in Copenhagen is the Palace of Rosenborg, standing at the end of a stately old garden - where it was built by Inigo Jones for Christian IV., and containing the room where the king died with his wedding dress, and most of his other clothes and possessions. This palace-building monarch celebrated for the drinking bouts in which he indulged with his brother-in-law, James I. of England, was the greatest dandy of his time, and before we leave Denmark we shall become very familiar with his portraits, always distinguished by the wonderful left whisker twisted into a pigtail falling on one side of the chin. Other rooms in Rosenborg are devoted to each of the succeeding sovereigns, and filled with relics and memorials which carry one back into most romantic corners of Danish history the ever-alternate succession of Christians and Fredericks making a most terrible bewilderment, down to the two English queens, Louisa the beloved and Caroline Matilda the unfortunate. Most curious amongst a myriad objects of value are the three great silver Lions - 'Great Belt, Little Belt, and Sound' - which, by ancient custom, appear as mourners at all the funerals of the sovereigns, accompanying them to Roeskilde and returning afterwards to the palace.

THE ROSENBORG PALACE, COPENHAGEN

Those interested in such matters will wander as we did through the more ancient parts of Copenhagen in search of old silver and specimens of the older Copenhagen china. Formerly the china imitated that of Miessen, but it has now a more distinctive character, and is chiefly used in reproducing the works of Thorwaldsen. Copenhagen has no other especial manufactures.

No visitors to the Danish capital must omit a visit to Tivoli, the pretty odd pleasure grounds - very respectable too - near the railway station, where all kinds of evening amusements are provided in illuminated gardens and woods by a tiny lake, really very pretty. Here we watched the cars rushing like a whirlwind down one hill and up another, with their inmates screaming in pleasurable agony; and saw the extraordinary feats of 'the Cannon King,' who tossed a cannon ball, catching it on his hands, his head, his feet - anywhere, and then stood in front of a cannon and was shot, receiving in his hands the ball, which did nothing worse than twist him round by its force.

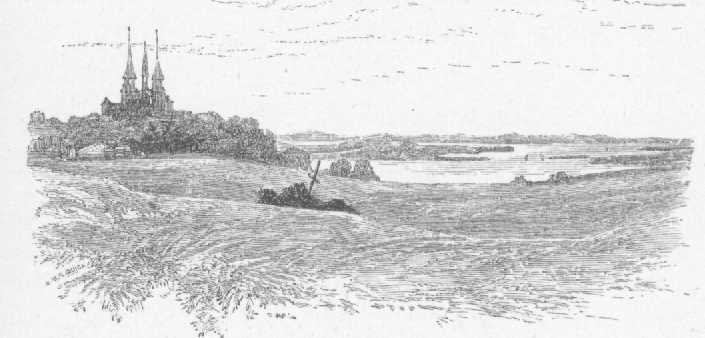

ROESKILDE.

One day we went out - an hour and a half by rail – to Roeskilde, where a church was first founded by William, an Englishman, in the days of King Harold Blaatand (Blue-tooth), brother of Canute the Great. It is dedicated to S. Lucius, because tradition tells that a terrible dragon, who infested the neighbouring fiord and banqueted on the inhabitants, was destroyed for ever when the head of the holy Pope S. Lucius was brought from Rome and presented for his breakfast. The tall spires of the cathedral rise, slender and grey, from the little town, and beneath, embosomed in sweeping cornfields, a lovely fiord stretches away into pale blue distances. Endless kings and queens are buried at Roeskilde. The earlier sovereigns have glorious tombs, amongst which the most conspicuous is that of Queen Margaret - 'the Semiramis of the North,' who, born in the prison of Syborg, where her unhappy mother Queen Helwig was imprisoned by Waldemar Atterhag, and allowed to run wild in the forest in her childhood, lived to become one of the wisest of Northern sovereigns, and to unite, by the Act known as 'the Union of Calmar,' the crowns of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, which attained unwonted prosperity under her sway. There are effigies of Frederic II. and Christian IV., the grandfather and uncle of our Charles I., which recall his type of countenance and have the same peaked beard. Christian IV., the great palace-builder, whose birth was believed to have been prophesied by the mermaid Isbrand, was born (April 12, 1577) under a hawthorn tree on the road between Frederiksborg and Roeskilde, as his mother, Sophia of Mecklenbourg, insisted on taking walks with her ladies in waiting far longer than was prudent. This king, his father, and all the later members of his royal house lie, not in their tombs, but in gorgeous coffins embossed with gold and silver upon the floor of the church, which has a very odd effect. The entrance of one of the private chapels is a gate with a huge figure, in wrought ironwork, of the devil with his tail in his hand. In another chapel are fine works of Marstrand (1810-75), the best of the pupils of Eckersberg, who gave the first stimulus to the art of painting in Denmark, where it has since attained to great eminence.

THE CASTLE OF FREDERIKSBORG.

The district around Roeskilde, and indeed the greater part of Denmark, is devoted to corn, for there is no country in Europe, except England and Belgium, which can compete with this as a corn-grower. It is curious that though the neighbouring Sweden and Norway are so covered with pines, no conifer will grow in Denmark except under most careful cultivation. The principal native tree is the beech, and the beech woods are nowhere more beautiful than in the neighbourhood of Copenhagen. The railway to Elsinore passes through the beautiful beech forests which are familiar to us through the stories of Hans Christian Andersen. Here, near a little roadside station, rises the Hampton Court of Denmark, the great Castle of Frederiksborg the most magnificent of the creations of Christian IV., which John of Friburg erected for that monarch, who looked personally into the minutest details of his expenses, and so raised this structure, glorious as it is, with an economy which greatly astonished his thrifty parliament. In the depths of the beech woods is a great lake, in the centre of which, on three islands united by bridges, rises the palace, most beautiful in its timehonoured hues of red brick and grey stone, with high roofs, richly sculptured windows, and wondrous towers and spires. Each view of the castle seems more picturesque than the last. It is a dream of architectural beauty, to which the great expanse of transparent waters and the deep verdure of the surrounding woods add a mysterious charm. A gigantic gate tower admits the visitor to the courtyard, where Christian IV., with his own hand, chopped off the head of the Master of the Mint, which he had established here, who had defrauded him. 'He tried to cheat us, but we have cheated him, for we have chopped his head off.' said the King. Inside, the palace has been gorgeously restored since a great fire by which it was terribly injured in 1859. The chapel, with the pew of Christian IV. - 'bedekammer,' prayer chamber, it is called - is most curious. There is a noble series of the pictures of the native artist Carl Bloch, recalling the works of Overbeck in their majesty and depth of feeling, but far more forcible.

A drive of four miles through beech woods leads to the comfortable later palace of Fredensborg, built as 'a Castle of Peace' by Frederick IV. and Louisa of Mecklenbourg, with a lovely garden, and a view of the Esrom lake down green glades, in one of which is a mysterious assembly of stone statues in Norwegian costumes.

CASTLE OF ELSINORE.

We may either take the railway or drive by Gurre from hence to Elsinore (Helsingor), where the great castle of Kronberg rises, with many towers built of grey stone, at the end of the little town on a low promontory jutting out into the sea. Stately avenues .surround its bastions, and it is delightful to walk upon the platform where the first scene of Shakspere's 'Hamlet' is laid, and to watch the numberless ships in the narrow Sound which divides Denmark and Sweden. The castle is in perfect preservation. It was formerly used as a palace. Anne of Denmark was married here by proxy to James VI. of Scotland, and here poor Caroline Matilda sate daily for hours at her prison window watching vainly for the fleet of England which she believed was coming to her rescue. Beyond the castle, a sandy plain reminding us of Scottish links, covered with bent-grass and drifted by seaweed, extends to Marienlyst, a little fashionable bathing place embosomed in verdure. Here a Carmelite convent was founded by the wife of Eric IX., that Queen Philippa - daughter of Henry IV. of England - who successfully defended Copenhagen against the Hanseatic League, but was afterwards beaten by her husband, because her ships were defeated at Stralsund, an indignity which drove her to a monastic life. Hamlet's Grave and Ophelia's Brook are shown at Marienlyst, having been invented for anxious inquirers by the complaisant inhabitants. Alas! both were unknown to Andersen, who lived here in his childhood, and it is provoking to learn that Hamlet had really no especial connection with Elsinore, and was the son of a Jutland pirate in the insignificant island of Mors. But Denmark is the very home of picturesque stories, which are kept alive there by the ballad literature of the land, chiefly of the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries, but still known to rich and poor alike as in no other country. For hundreds of years these poetical histories have been the tunes to which, in winter, when no other exercisc can be taken, people dance for hours, holding each other's hands in two lines, making three steps forwards and backwards, keeping time, balancing, or remaining still for a moment, as they sing one of their old ballads or its refrain.

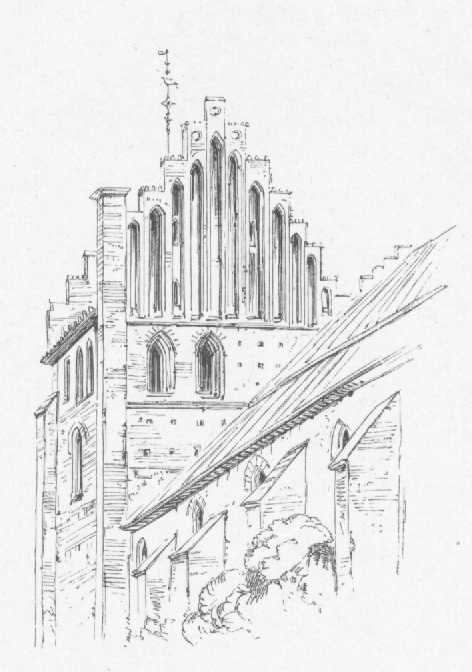

TOWER OF HELSINGBORG CHURCH

It was in a wild evening, with huge blue foam-crested waves rushing down the Sound, that we crossed in ten minutes to Helsingborg in Sweden, mounted for the sunset to the one huge remaining tower of its castle, and sketched as typical of almost all village towers in Denmark the belfry of the church where King Eric Menred was married to the Swedish princess Ingeborga.

In Sweden