IN SWEDEN

IT is not beautiful in Sweden, but it is very pretty; if everything were not so very much alike, it would be very pretty indeed. The whole country as far north as Upsala is like an exaggerated Surrey - little hills covered with fir-woods and bilberries, brilliant, glistening little lakes sleeping in sandy hollows, but all just like one another.

We turned aside in our way from Helsingborg to the north to visit the old university of Lund, the Oxford of Sweden, a sleepy city, where the students lead a separate life in lodgings of their own, only being united in the public lectures; for in Sweden, as in Italy, the taking of a degree only proves that the graduates have passed a certain number of examinations, not, as in England, that they have lived together for three years at least, forming their character and taste by mutual companionship and intimacy. The cathedral of Lund is a most noble Norman building, with giants and dwarfs sculptured against the pillars of its grand crypt, and a glorious archbishop's tomb, green and mossy with damp.

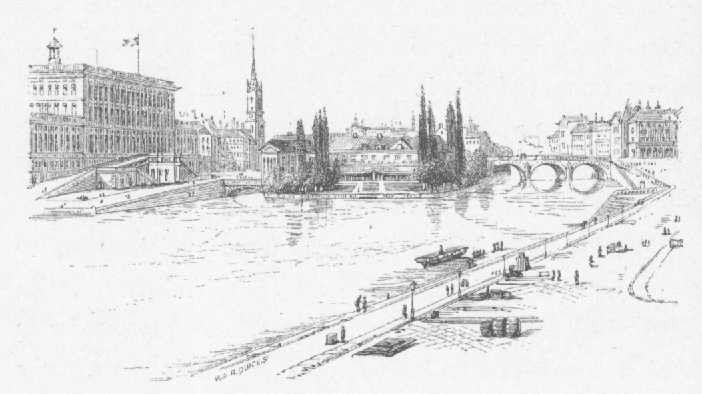

An immense railway journey, by day and night through the endless forests, brought us to Stockholm, where we arrived in the early morning. Though the town is little beyond an ugly collection of featureless modern streets, the situation is quite exquisite, for the city occupies a succession of islets between Lake Malar and the Baltic, surrounding, on a central isle, the huge Palace built from stately designs of Count Tessin in the middle of the last century, and the old church of Riddarholmen, where Gustavus Adolphus and many other royal persons repose beneath the banner-hung arches.

THE JUNCTION OF LAKE MALAR AND THE BALTIC, STOCKHOLM.

It sounds odd, but, next to the Palace, the most imposing building in Stockholm is certainly the Grand Hotel Rydberg, which is most comfortable and economical, in spite of its palatial aspect. There is no table d'hôte, and everything is paid for at the time, in the excellent restaurant on the first floor of the hotel. Here, a side table is always covered with dainties peculiarly Swedish, corn and birch brandy, and different kinds of potted fish, with fresh butter and olives, and it is the universal custom in Sweden to attack the side table before sitting down to the regular dinner. The rooms in the hotel are excellent, and their front windows overlook all that is most characteristic in Stockholm - the glorious view down the fiord of the Baltic: its farther hilly bank covered with houses and churches; the bridge at the junction of the Baltic and Lake Malar, which is the centre of life in the capital, and the little pleasure garden below, where hundreds of people are constantly eating and drinking under the trees, and whence strains of music are wafted late into the summer night; the mighty palace dominating the principal island, and the little steam gondolas, filled with people, which dart and hiss through the waters from one island to another. In Stockholm, where waters are many and bridges few, these steam gondolas are the chief means of communication, and we made great use of them, the passages costing twelve oëre, or one penny. The great white sea-gulls, poising over the water-streets or floating upon the waves, are also a striking feature.

The museums of Stockholm have little to call for any especial notice, except a grand statue of the sleeping Endymion from the Villa Adriana, and the curious collection of royal clothes down to the present date, a gallery of costume like that which once existed in London at the Tower Royal. The chief curiosity which the Swedish collection contains is the hat worn by Charles XII. when he was killed, in which the upward progicss of the bullet can be traced, proving that the king's death was caused by an assassin, and not the result of a chance shot from the walls of Frederikshald. No especial features mark the interior of the Palace, though the Royal Stable for a hundred and forty-six horses is worthy of a visit; and the churches are uninteresting, except perhaps S. Nicholas, the coronation church, which contains the helmet and spurs of S. Olaf, stolen from Throndtjem. Riddarholmen can scarcely be regarded as a church it is rather a great sepulchral hall hung with trophies, having a few tombs on the floor of the building, and vaults opening under the side walls, in which the different groups of royal persons are buried together in families. Under a chapel on the left lies Gustavus Adolphus, the justly popular great-grandson of Gustavus Wasa, who fell at the battle of Lutzen, and who, as soldier, general, and king, ever knew true merit, and laboured for the glory of his country rather than for his own. In the opposite chapel repose the present royal family, descendants of Bernadotte, Prince of Pontecorvo, the only one of Napoleon's generals whose dynasty still occupies a throne. He began life as a common soldier, and his election as Charles XIV. of Sweden was chiefly due to the kindness with which he treated Swedish prisoners taken in the Pomeranian wars. But the Swedes have never had cause to repent of their choice, and their reigning house is probably the most popular in Europe. The coffins of those members of the royal family who have died within the memory of man are ever laden with fresh flowers.

Close by the Riddarholmen Church is the most picturesque bit of street architecture in Stockholm, where a statue of Burger Jarl, the traditional founder of the town, forms a foreground to the chapel of Gustavus Adolphus and one of the many bridges.

In saying that Stockholm is not picturesque one may seem to have spoken disparagingly, but, nevertheless, it is perfectly charming: there is so much life and movement upon its blue waters, and its many little public gardens give such a gay aspect to the buildings. Of these, the chief is the Kongsträgården, surrounding a statue of Charles XIII., where the pleasant Café Blanche is filled all the evening with an animated crowd, gossiping and eating ices under the verandah and shrubberies, and listening to the music. While we were staying in Stockholm a hundred Upsala students came in their white caps to sing national melodies in the Catherina Church. We lived through two hours of fearful heat to hear them, and most beautiful it was. King Oscar II. was present - a noble royal figure and handsome face. He is the ideal sovereign of the age - artist, poet, musician, student, equally at home in ancient and modern languages, profoundly versed in all his duties, and nobly performing them.

RIDDARHOLMEN, STOCKHOLM.

We had intended going often, as the natives do, to dine amongst the trees and flowers at Hasselbacken, in the Djurgården, a wooded promontory, to which little steamers are always plying, but, alas! during eight of the ten July days we spent at Stockholm it rained incessantly. We were so cold that we were thankful for all the winter clothes we brought with us, and were filled with pity for the poor Swedes in being cheated out of their short summer, of which every day is precious. The streets were always sopping, but, in the covered gondolas, we managed several excursions to quiet, damp palaces on the banks of lonely fiords - Rosendal, remarkable for a grand porphyry vase in a brilliant little flower garden and Ulriksdal, with its clipped avenues and melancholy creek.

Our limited knowledge of Swedish often caused us to embark in amusing ignorance as to whither we were going, and led us into many a surprise. One day we set off, intending to go to Drottningholm, but, on reaching the quay, found the steamer just gone. At that moment such a fearful storm of rain came on that we were obliged to rush for shelter wherever we could, and the nearest point of refuge was the deck of the steamer Mary, which instantly started. We feared we might be bound for the Baltic, and, failing to make any one understand us, resolved to disembark at the first landing-place. But then the rain was worse than ever, and we allowed ourselves to be carried on down Lake Malar, till our boat turned into a little creek, and landed us on the pier of a manufacturing town. We had not reached the end of the pier, however, before the rain came on again in such convulsive torrents that we fled back to the Mary, which again started on its travels, and this time, after stopping at many little ports, conveyed us back to Stockholm. When we asked the captain what we were to pay for our voyage, he said, 'Oh, nothing;' and very much amused he and his crew seemed to be by our ignorance and adventures.

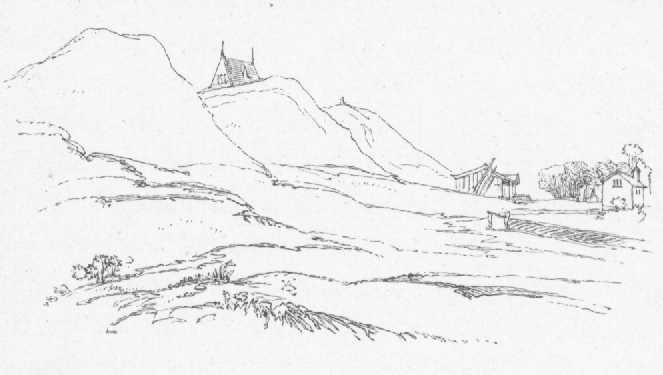

THE GRAVES OF THE GODS.

We had a fine day for our excursion by railway to Upsala, whence we hired a little carriage to take us on to Old Upsala, about three miles distant. A drive across a dull, marshy plain brings one to a delightfully wild district of downs, covered with hundreds of little sepulchral mounds like Wiltshire harrows, amid which three great tumuli, standing close together, are said to mark the graves of Odin, Thor, and Freya - heroes in their lifetime, gods in their death. Close beside them for centuries rose the temple which was the most sacred shrine of Scandinavian worship. It glittered all over with gold, and a golden chain, nine hundred ells in circumference, ran round its roof. In the temple were three statues, around which hovered all the principal mythological traditions of the north. The central figure was that of Odin or Wodan, the wizard-king, who is said to have come in the dawn of Swedish history from his domains of Asir, which extended from the Euxine to the Caspian, and whose capital was Asgard. He landed in Funen, where he founded Odense, and left his son Skjöld as a sovereign. Thence he passed into Sweden, and established his government at Sigtuna, not far from Upsala. His existence is affirmed by the Saxon Chronicle. He was called 'the Father of Victory,' for if he laid his hands on the heads of his generals, and predicted their success when they went out to battle, that success never failed them. He was also, says Snorro Sturlesen, 'the Father of all the arts of modern Europe.' Tradition has endowed him with every miraculous power. He could change his looks at pleasure - to his friends most beautiful, but a demon to his enemies. By his eloquence he captivated all who heard him, and as he always spoke in verse he was called 'the Artificer of Song.' His verses were endowed with such magic power that they could strike his enemies with blindness or deafness, or could blunt their weapons. To listen to the sweetness of his music even the ghosts would come forth and the mountains would unfold their inmost recesses. He was the inventor of Runic characters. He could slaughter thousands at a blow, and he could render his own followers invulnerable. At his will he could assume the form of beasts at his word the fire would cease to burn, the wind to blow, or the sea to rage. If he hurled his spear between two armies, it secured victory to those on whose side it fell. The dwarfs (Lapps) had built for him a ship called Skidbladner; in which he could cross the most dangerous seas with safety but when he did not want to use it, he could fold it up like a handkerchief. Everything was known to Odin, for did he not possess the mummified head of his enemy Mimir, which was all-wise, and he had only to consult it? Yet, with all these gifts and attributes, Odin remained human; he had no power over death. When he felt his end approaching he assembled all his friends and followers, and, giving himself nine wounds in a circle, allowed himself to bleed to death. The body of the great chieftain was burnt and his ashes were buried under the mound of Upsala; but his spirit was believed to have gone back to the marvellous home in the Valhalla of Asgard, of which he had so often spoken, and whither he had always said that he should return. Henceforward it was considered that all blessings and mercies were gifts sent by Odin. The younger Edda tells that all who die in battle are Odin's adopted children. The Valkyriae pick them out upon the battle-field and conduct them to the Valhalla, where they have perpetual life in the halls of Odin. Their days are spent in hunting or the joys of imaginary combats, and they return at night to feast upon the inexhaustible flesh of the boar Sahrimnir, and to drink, out of horn cups, the mead formed from the milk of a single goat, which is strong enough nightly to intoxicate all the heroes. Huge logs constantly burn within the palace of Odin, for warmth is the northern idea of heaven, while in their hell it is eternal winter. When a Scandinavian chieftain died in battle, not only were his war-horse and all his gold and silver placed upon his funeral-pyre, but all his followers slew themselves that he might enter the halls of Odin properly attended. The more glorious the chieftain the greater the number who must accompany him to Valhalla. To rejoin Odin in Asgard became the height of a warrior's ambition. It is recorded of Ragnar Lodbrok that when he was dying no word of lamentation was heard from him: on the contrary, he was transported with joy as he thought of the feast preparing for him in Odin's palace. ' Soon, soon,' he exclaimed, 'I shall be seated in the pleasant habitation of the gods, and drinking mead out of carved horns! A brave man does not dread death, and I shall utter no word of fear as I enter the halls of Odin.' But stranger than all the legends concerning Odin is the fact that his memory is still so far fresh that 'Go to Odin' is yet used by the common people where an uncivil wish as to the lower regions would find expression in England. The fourth day of the week still com memorates Odin or Wodan - in old Norse Odinsdgr, in Swedish and Danish Onsdag, in English Wednesday.

On the right hand of Odin, in the temple of Upsala, sate the statue of Freyja, or Freyer, represented as a hermaphrodite, with the attributes of productiveness. Freyja was the goddess of love, who rode in a car drawn by wild cats. She knew beforehand all that would happen, and divided the souls of the dead with Odin. She is commemorated in the sixth day of the week, that Freytag or Freyja's Day which in Latin is Dies Veneris, or Venus' Day.

On the left of Odin sate Thor, who, says the Edda, was 'the most valiant of the sons of Odin.' He was the offspring of Odin and Frigga, 'the mother of the gods,' and the brother of 'Balder the Beautiful.' As the defender and avenger of the gods, he was represented as carrying the hammer with which he destroyed the giants, and which always returned to his hand when he threw it. He wore iron gauntlets, and had a girdle which doubled his strength when he put it on. The fifth day of the week was sacred to Thor, in old Norse Thórsdag, in Swedish and Danish Torsdag, in English Thursday ; in Latin Dies Jovis, for Jupiter, the God of Thunder, had the same attributes as Thor.

There were three great festivals at Upsala, when multitudes flocked to the temple to consult its famous oracles or to sacrifice. The first was the winter festival of 'Mother Night' - saturnalia in honour of Frey, or the sun, to invoke the blessings of a fruitful year the second feast was in honour of the Earth; the third was in honour of Odin, to propitiate the Father of Battles. Every ninth year, at least, the king and all persons of distinction were expected to appear before the great temple, and nine victims were chosen for human sacrifice - captives in time of war, slaves in time of peace - 'I send thee to Odin' being the consolatory last words spoken to each as he fell. If public calamities had been caused by any royal mismanagement, the people chose their king as a sacrifice; thus the first king of the petty province of Vermeland was burnt to appease Odin during a famine. It is also recorded that King Aun sacrificed his nine sons to obtain a prolongation of his own life. The victims were either hewn down or burnt in the temple itself, or hung in the grove adjoining – 'Odin's Grove' - of which every leaf was sacred. Still, according to the Voluspa, the famous prophecy of Vela, at the end of the world even Odin, with all the other pagan deities, will perish in the general chaos, when a new earth of celestial beauty will arise upon the ruins of the old.

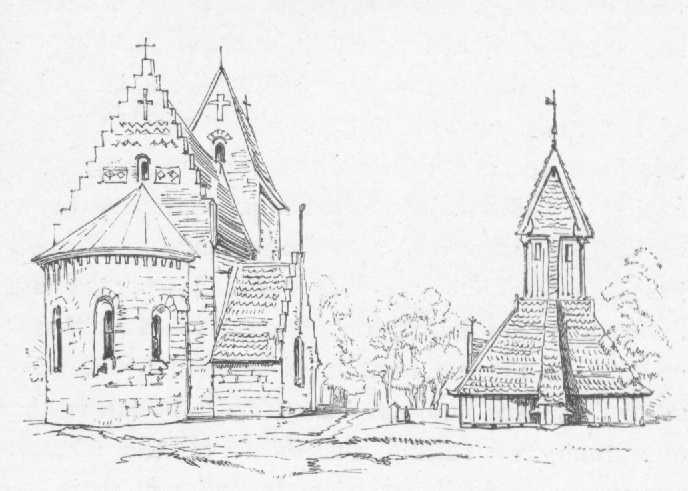

THE CHURCH OF OLD UPSALA.

One of the most curious little churches in Christendom now stands upon the site of the ancient temple. The apse is evidently built out of the pagan sanctuary. The belfry, Swedish-fashion, is detached, built of massive timbers and painted bright red. There are scarcely any human habitations near, only the mighty barrows, overgrown with wild thyme and a thousand other flowers, which rise over the graves of the gods. In the tomb of Odin the Government still gives the mead, which was the nectar of Scandinavian heroes, to pilgrim visitors.

Like most of the Swedish towns, Upsala is disappointing, and its mean, ill-paved streets show few signs of antiquity. At the east end of the cathedral is the lofty tomb of Gustavus Wasa, the first Protestant King of Sweden, whose effigy lies between the charming figures of his two pretty little wives. In 1519 he was carried off as a hostage by that Christian, King of Denmark, who forcibly made himself King of Sweden also, and ruled with savage tyranny. Escaping to Lubeck, he headed a revolutionary party against the tyrant, and, after many defeats, succeeded in taking Stockholm, where he was made king in 1523. Soon after, Olaf Petri's translation of the New Testament led to the Reformation in Sweden, where Gustavus Wasa was another Henry VIII., in taking the opportunity of seizing two-thirds of the Church revenues, and depriving all ecclesiastics of their incomes if they refused to embrace Lutheranism. One of his daughters-in-law was the famous Polish princess, Queen Catherine Jagellonica, who tried hard to upset the new religion, and inculcated Catholicism upon her son, King Sigismund, who was deposed, on religious grounds, in favour of his uncle, Charles IX., the father of Gustavus Adolphus. This Queen Catherine Jagellonica has a fine tomb in a side chapel of Upsala Cathedral.

GRIPSHOLM.

On a brilliant July morning we embarked at Stockholm in the steamer which runs twice a week down Lake Malar to Gripsholm. Most lovely were the long reaches of still water with their fringe of russet rocks, every crevice tufted with birch and dwarf mountain ash, opening here and there to show some red timber houses or a wooden spire. It was several hours of soft diorama, with the music of the pines, before the great castle of Gripsholm, the Windsor of Sweden, came in sight, with its many red towers and Eastern-looking domes and cupolas. We were landed at the little pier of Mariefred, in itself a lovely scene, with old trees feathering into the water, and a picturesque church rising in a grove of walnuts on a green hill behind. Hard by is a little inn where the whole of the passengers in the steamer dined together, at many little tables, the great staple of food being fresh trout and salmon of the lake, the bilberries and cloudberries of the rocks, and the birch brandy and wild strawberries from the woods. After dinner every one trooped along the meadow paths to the castle, and rambled in friendly companionship over its numerous rooms, full of interest, and with many curious royal portraits and pieces of ancient furniture. There are endless historic recollections connected with Gripsholm, but they centre for the most part around the sons of Gustavus Wasa. Of these, John was immured here by Eric XIV., with his wife Catherine Jagellonica, who, during her imprisonment, gave birth to her son Sigismund (afterwards Sigismund III. of Poland), in a box-bed which still remains. Eric intended to have put his brother to death, but when he entered his cell for the purpose was so overcome by fraternal feeling that he begged his pardon instead. That pardon was not granted, for when John got the upper hand he imprisoned Eric in a small chamber at the top of the castle, where he languished for ten years, during which he wrote a treatise on military art, and translated the history of Johannes Magnus, and where - in the end – he was poisoned.

In Norway