PARAY LE MONIAL

TRAVELLERS often complain of the dulness of the journey through France which they are forced to take in the search after a warm winter climate. They think there is nothing to see between Paris and Marseilles, because they never look. Yet even the traveller who is hurried straight on without stopping might find much to interest him in the rapid transitions - the extraordinary changes in all the characteristics of the country he is passing through. First come the central plains of France; then the rolling hills of Burgundy in the white moonlight; then the great towns, Dijon and Lyons, deep down below and mapped out in the night by their lamps; the dawn over the Rhone valley, with its arid hills and crumbling castles; the change to the blue sky fading into softest amber; the first stunted olives; the white roads leading, dust-surrounded, to the white Provençal cities, Avignon, Tarascon, and Arles; the desolate stone-laden Crau, so utterly forlorn that it seems like the world of another life; the still blue Mediterranean with its fringes of pink-blossoming almonds growing in thickets of asphodel and violets; Marseilles, and its harbour and its shipping, and its thousand bastides gleaming snowy-white amid the foliage on the hillsides; and lastly, the granite phase near the coast, and its peculiar growth of heath and lavender, and rosemary and pines. Even the winter traveller who is ill-tempered and in a hurry ought not to say that he can find nothing to admire.

But for those who have time to break their journey and to linger on the way, no words can portray the wealth of interest and pleasure and instruction which may be found, and which too often passes unheeded and unsought, in the charming little French towns by the wayside. The writer's own feeling is that his pleasantest Continental days, those which come back to him most in dreams, those which he delights to linger over in memory, are not days spent in the great well-known sight-seeing places, Rome, Florence, Venice, Dresden, or Vienna; not even days amid the greatest beauties of the Alps or the Pyrenees; but those passed in lingering in the little wayside towns of France and Germany. Seldom compelled to hurry, in annual journeys to and from the south, short mornings were spent in the railway, generally in reading up the story of the places to be visited, and happy afternoons in rambling about old churches too big and too grand for the little towns they adorned, in sketching the ruins of some forgotten abbey by a willow-fringed river, or hearing some charming story of happy, and often holy and beautiful, peasant life from simple and friendly lips. Delightful too were the evenings in the primitive clean country inns - not great Anglicised houses, with the vulgarity and ostentation which generally follow the word "hotel," and which always attend the places whither couriers drag their long-suffering victims, but simple homes with a welcome from simple hearts, quiet cheerful wholesome dinners at bright little tables d'hôte, where the mistress alternately carved and pressed her home-made dainties, and where the master formed one of the company - the humble village magnates, the doctor, the attorney, perhaps the mayor, and sometimes a stranger or two, making up the rest of the party. And then would come the rest in snowy beds, whose sheets were scented with lavender, in little rooms with brick floors and a single strip of carpet, and a china bénitier, with a bunch of box blessed on Palm Sunday, hanging against the whitewashed wall at the bed's head; and the being awakened by the hostess calling her chickens under the window, to the rippling of the river through the orchards, and the sweet scent of the lime-flowers which hung over the little garden.

Such days as these may be spent at many of the places between Paris and Marseilles - at Fontainebleau, with its delightful palace-garden and its green forest alleys; at Sens, with its grey cathedral and memories of Becket; at Auxerre, with its excursions to the abbeys of Pontigny and Vezelay; at Tonnerre, with its interesting churches and hospital and tombs; at Montbard, with its lovely river and its beautiful abbey of Fontenay; at Dijon, with its delightful walk to the hill of Fontaines; at Nuits, with its glorious old church and its excursion to Citeaux; at Beaune, with its chestnut-girded ramparts and mediæval streets; at Autun, with its Roman remains and glorious cathedral; at Villefranche, for the sake of Ars and its memories, and at many places farther on, and, being more in the south, perhaps better known than these.

Circumstances certainly have a strange power of gilding, and there are companionships which make almost all scenes beautiful, and which seem to gather up the flowers of life and weave them involuntarily into a garland of perfect happiness. When the golden cord which twined it is broken, the garland withers. Nothing can ever be quite the same again, the delicate lines seem washed out of the picture, the pathos lost which made the poem, and yet, even then, it will often be found that Nature, especially in her quiet moods (and under the expression Nature, one may be allowed to mean all old "unrestored" buildings, for which Time has done more than even the builder), has a wonderful power of comfort and companionship.

Once I was alone at Macon, where we had often been before.

Macon is one of the places which people find most fault with, but which we have always liked. It has so completely a character of its own, with its long quay of quaint houses, two miles long I should think, facing the immense river, which has nothing beyond it, but which makes a great angle just fronting the centre of the town, and so sweeps all its impurities away to the rich distant pasture-lands, and leaves you to that fresh pure air which is now looked upon as a cure for Roman fever, and which is perfectly impregnated in May and June with the scent of lime avenues; for here as well as at Tonnerre people cultivate the lime-flowers - tilleuls - and gather them in a regular harvest, to dry and sell to the apothecaries to mix with their tisanes. Indeed no old French wife who knows her duty ever dreams of being without a good supply of dried fleurs de tilleul to take in boiling water, with a feuille d'oranger and a teaspoonful of Eau de Melisse des Carmes, for a cold, or hysteria, or indigestion, or sleeplessness, or headache, or . . . almost everything.

The ruined cathedral of Macon, battered to pieces at the Revolution, stands with its two octagonal towers looking down upon the quiet market-place. The back part of the town is so deserted, so silent and grass-grown, that you might think you were in a Spanish city. The high walls of convents, with richly wrought heavy rails before the windows, throw a gloom over the narrow streets. Here and there the lines of houses are broken by a courtyard with acacias and lilacs, before one of the ancient Hôtels, which in winter receive the provincial noblesse. The whole life of Macon seems to be concentrated by the river-side, which is the scene of constant change from the quantity of merchandise from the south of France, and the produce of the Maconnais vineyards, which is always being disembarked or embarked. Here also, for those who know the beauty of simple lines, there is a charm in the country seen beyond the river: -

" Large and strange,

Crossed everywhere by long thin poplar-lines,

Like fingers of some ghastly skeleton-hand,"

pointing at the town. There is a charm, and a great one, in the Inn, which faces the broad gleaming water, to which you look across the rugged pavement of the street, between great green boxes, set out on the edge of the pavement, and planted with huge tufts of white marguerites and Portugal-laurels clipped round to look like orange-trees.

In the end of May there is always a great fair at Macon, which is resorted to by the whole country-side. Then the usually quiet town assumes a festal aspect, the walks under the lime-trees are lined with booths filled with gay wares and most brilliantly lighted towards evening, and in the little place are numbers of shows-theatres, and operas, and horsemanship - at one sous of entrance money, between which a merry crowd wanders and laughs and chatters, entering first Le Théâtre de Jésus, and then rushing to see La Vraie Femme à la Barbe, who is exhibiting next door. The most popular, and certainly the most exciting, of all these spectacles on our last visit was the Massacre of the Innocents, but then three sous were charged for that. It was an awful tableau. Soldiers were holding numbers of little children, without a vestige of garments, head downwards by their feet; some were being slaughtered and apparently pouring with blood while others were lying weltering in their gore at the feet of their agonised mothers. It was wonderfully done - far too horrible, and much more vivid than the famous picture of Guido. The crowd at the fair was so great and the weather so beautiful, that late at night, when the little theatres were all closing, and the shops were putting away their wares, Macon invented a new amusement, a fiery regatta on the broad limpid river, boats which chased each other, wreathed from end to end with garlands of coloured lamps, reflected a thousandfold in every little riplet. They pursued, they escaped, they turned, they pursued again, the crews sang and the people cheered, and, as our landlady said, "il avait l'air tout-à-fait Venitien."

But lately the peasants who have come into the Macon fair from the neighbouring towns - from Bourg, and Chagny, Chalons, Autun, and Lyons - have extended their journey a little farther, and taken the opportunity of mingling a religious duty with a secular one, by making the pilgrimage to the shrine of Paray le Monial, which has only lately become a familiar name to Protestant England, though in France it has long been honoured.

Since 1864, when the nun Marguerite-Marie Alacoque, who had died in 1690, received the tardy honours of "beatification," the interest in the place where her life was spent and where she lies buried has been gradually and steadily increasing. Before this, its noble old church attracted few but local visitors, and in England it was quite unknown: in Murray's Handbook it was not even mentioned. But the erection and opening of a new church above the grave of the saintly woman in June 1866, and the announcement in the following September that steps were being taken at Rome for her future canonisation, became the signal for an extraordinary furore about her. English Catholics began to say to one another, "We must increase the devotion to the Mère Marguerite-Marie Alacoque; this is a thing to be done," - and no energy has been wanting to fan the flicker of enthusiasm about her into a flame, which finally blazed forth at the time of the Sardinian occupation of Rome, when the neglected and almost lost saint was invoked by a myriad voices, and her intercession sought in favour of the dethroned Pope, who was even then employed in doing her honour. Since then the "devotion" has grown in a way which is simply marvellous. By dint of preachings and persuasions, pilgrimages in her honour were established in 1873 even in unenthusiastic England (though it must be owned that many of the nominal "pilgrims" paid their visits by proxy), and in France processions with banners and chaunts streamed forth from every province in honour of the poor nun who had died nearly 200 years before, and with the hope of her influence in reestablishing the temporal kingdom of the Pope.

For a long time Paray le Monial was only accessible by a branch line from Chagny, but now it has its own separate line from Macon, which is only used by the pilgrims and by the working people of the country.

The district this railway passes through must be bleak and bare in winter, but in summer it is charming. The undulating uplands swell into free heights covered with heath or golden with broom, while here and there a granite fragment crops up above the short grass. The lower slopes are rich with vineyards, the vines being tied to low posts and cut close to the ground. At wide intervals come the villages clustering round their churches, which are almost always more or less picturesque. In the hollows, poplars fringe the abundant streams, and rows of luxuriant walnuts mark the divisions between the fields of clover and lucerne. By the side of the railroad the common flowers of France grow together most luxuriantly - scabious, salvia, mignonette, hawkweed, and here and there masses of dark blue columbine.

It is the country where the childhood of Lamartine was spent, and of which he gives so vivid a description in his "Confidences." One may still see amid its trees the low pyramidal spire at his paternal home of Milly. One may follow the stony path which he describes as winding from door to door between the cottages amid which the little château stands like a great pillar of blackened stone, in its tiny garden surrounded by a low dark wall, behind which the hill begins to rise at once imperceptibly - treeless, shrubless, yet green in summer with vines. “This was all," wrote Lamartine - "yet it is that which sufficed for so many years for the happiness, the thoughts, the peaceful work and leisure of my father, my mother, and their eight children. It is that which now forms the centre of their recollections. It is the Eden of our childhood, and we could wish that the world began and ended for us with the walls of this poor enclosure."

Not far distant we may also see Monceaux, the château which was the home of Lamartine's later life. It stands beautifully situated on a rising ground amid the vineyards, surrounded by tall trees. In 1870 the writer was present there at the sale, when all the sacred household relics were first exposed to the curiosity of the countryside and then put up to auction in the little chestnut avenue, where the bidders sat pleasantly all through the hot summer day upon the grass; and he secured as a precious memorial, for a few francs, the old green satin quilt which covered the bed of the sweet woman whose saintly life is laid open to us in Le Manuscrit de ma Mère. After reading her journal, the whole of this country seems fragrant with the recollection of her, and it was over these hills that the peasantry of Milly carried their beloved mistress at midnight, through the deep untrodden snow, to her last resting-place at Saint-Point.

There are numbers of old châteaux like that of Monceaux dominating the Maconnais vineyards, simple old country-houses, distinguished by their manorial dovecotes, and standing on heights in an enclosure surrounded by a wall. The owners are quiet folk, often proud enough of their "blue blood;" but leading simple, sleepy lives, with few other diversions than occasional visits to neighbouring châteaux, as sleepy as their own, and only a few miles distant, or the being occasionally joined by the priest or the doctor in a game of bowls upon their terrace.

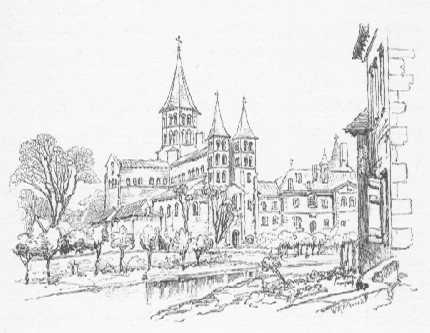

As we advance into the hills, the lines of poplars draw together as the uplands close in. Here is Cluny with its glorious Benedictine abbey, of which so large a portion remains the abbey which furnished the line of German pontiffs to the Papacy, and trained its Prior Hildebrand for the Papal throne and placed him upon it.

The train stops everywhere. It has superseded all other means of locomotion in this quiet agricultural country, and it is the country people who are considered. At all the stations are groups of working men getting in and out in their blue blouses, and women in their blue aprons and their caps with flapping crimped white fringes. Endless are the little excursions which the train makes out of each of the stations, returning to it again before it finally moves on. But in the train, besides the country people with their baskets and umbrellas (of course we are going second class - and how much the pleasantest class it is!) are Sisters of Charity, priests with their breviaries and ever-moving but silent lips, and women in the Macon head-dress - the lofty little tower of straw, rising from a brim shaded by long black lace lappets; and all these are on pilgrimage.

The country opens again now. The fields are pasture-land, mistletoe grows in the orchards, the vegetation becomes poorer, and here, stranded on the wind-stricken upland, is a brown Burgundy town, with high roofs and dormer windows. It is Paray le Monial.

At the close of the seventeenth century, when the rapid growth of Jansenism was agitating the Roman Church, the Jesuit party sought for some new influence which might stimulate the flagging energies of ultra-Roman Catholicism. This influence was unexpectedly found in a poor nun of Paray le Monial, who came, like St. Catherine of Siena, though by a very different path, and partly under the influence of the strangest fanaticism, to the rescue of her Church, as the foundress of the new form of devotion known as the "Adoration of the Sacred Heart."

PARAY LE MONIAL

The Order of the Sisters of the Visitation, a branch of the Carmelites, had been founded by St. Francois de Sales, and one of their convents was early established at Paray. Here was received as a nun, in her twenty-third year, in 1671, Marguerite, the daughter of Claude Alacoque, a small proprietor at Veroure, near Autun, and of Philiberte Lamyn, his wife. On entering the convent, Marguerite adopted in religion the name of Marie, which she affixed to her own. From the age of four she is said to have been devoted to pious thoughts and acts, and she had always loved solitude. Her parents had wished her to marry, and on finding her impracticable, besought her, in choosing a convent, to join the Ursulines of Macon, whose abbess was her relation; but she insisted upon selecting an Order more exclusively devoted to the honour of the Virgin.

Being of delicate health, and suffering cruelly from self-inflicted macerations, Marguerite-Marie Alacoque soon fell into a visionary state, which increased till her religious transports began to take a miraculous form. Even then there is something most sincere and touching in her desire to shrink from notoriety, and her own simple dread lest her fancies should be delusions. "I constantly fear lest, being mistaken myself, I should mislead others," she wrote to her confessor. "I pray constantly to God that He will permit me to be unknown, lost, and buried in lasting oblivion. My Divine Master has required of me by my obedience that I should write to you, but I cannot and do not believe that it can be His will that any recollection should remain after death of so pitiful a creature.

She appears to have forgotten all else in the longing after a complete heart-union with her Saviour. "I desire," she wrote to one who asked her advice, "nothing more than to be blind and ignorant as regards human affairs, in order perfectly to learn the lesson I so much need, that a good nun must leave all to find God, be ignorant of all else to know Him, forget all else to possess Him, do and suffer all in order to learn to love Him." Many of her letters now exist, of which a great portion were written to a certain Father La Colombière, who was then living in St. James's Palace, as one of the chaplains of Catherine of Braganza, Queen of Charles II. Those who read them will feel that, however imaginative and ecstatic she was, she had at least a firm faith in the facts and feelings she narrates, and a simple anxiety that while she, the instrument, was forgotten, the narration of them might redound to the glory of God. In the early part of her life at the convent, she seems to have been really anxious to counteract by honest practical work the increase of her visionary tendency, and we find her in turn fulfilling the offices of "infirmarian," "mistress of the children," and "mistress of the novices." Many of her letters at this time might be mistaken for those of St. Teresa; for instance: -

“I would wish to love my Love with a love as piercing as that of the seraphim, and I should not grieve if it must be from Hell that I should love Him thus." And again: - "Nothing that the world can give would be more pleasing to me than the cross of my Divine Master, a cross exactly like His, that is, heavy, ignominious, painful, comfortless, pitiless. Others have the happiness of mounting with the Divine Master upon Tabor, but I am content to know no other path than that of Calvary, to spend my whole existence amid the thorns, the nails the blows of the cross, with no other pleasure than that of knowing that this world has no pleasure to give me." Yet shortly after her writing thus, the simple truth of her natural character is shown by her adding - "Alas! how I fear that this very thirst for suffering may perhaps in itself be a temptation of the Devil."

"As to her prayers for suffering," rather quaintly says one of her biographers, "they were most abundantly answered. Her life in the convent was one of constant and acute pain; agonising neuralgia and rheumatism allowed her no rest, and her only comfort was in frequent communion - what she called the reception of 'the Bread of Love.'"

"I have such a thirst for communion," she wrote, "that I feel if I had to reach it barefoot through a path of flame, it would cost me nothing in comparison of being deprived of it."

Gradually, as her sickness and her self-inflicted penances increased, her religious fervour began to border upon insanity. That which might profitably be understood in an allegorical sense was by her taken as an actual and literal occurrence. Her Saviour, she believed, constantly spoke to her. He addressed her from the Sacrament of the Altar; He met her beneath the walnut-trees in the garden; He showed her His wounds, which He said were still bleeding from the persecutions of living unbelievers. He told her that the hour of divine vengeance was at hand, and she interceded with Him, as Abraham did with the Almighty on behalf of Sodom and Gomorrah. One day He said to her, "I search a victim for my heart, who will offer herself up as a sacrifice for the accomplishment of my designs." Then in her "longing after the presence of divine love," she offered her own heart to the Saviour, and He accepted it. Visibly and actually, as she believed and described (always under the promise of secrecy to those who swore it and immediately betrayed it), visibly and actually the Saviour received her heart, and placed it within His own, which she said that she "saw through the wound in His sacred side, and that it was burning like the sun, or like a fiery furnace." Her own heart at the same time appeared "like an atom which was being consumed in this furnace." And when it was entirely aflame "Our Saviour placed it again in the side of His servant," saying, "Receive, my beloved, the pledge of my love." From this time Marguerite-Marie was possessed by one idea alone - the promulgation of the worship of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in its actual and literal sense. Persecuted at first, and laughed at by her own Sisterhood, she gradually gained an ascendancy over them, and henceforth believing that God had given her a mission to accomplish, she threw aside, in what she fancied to be His cause, all feelings of personal reticence, urging upon the world, in her letters and words, the adoration of the Sacred Heart, and announcing the eleven benefits which her vivid imagination assured her that her Saviour had verbally promised to those who would honour Him under this peculiar form: - 1. All the graces necessary for their condition of life. 2. Peace in their families. 3. Consolation in their sufferings. 4. A refuge in Christ during their life, and more especially at their death. 5. Abundant blessings on all their enterprises. 6. That sinners should find in the Sacred Heart the source and infinite ocean of piety. 7. That through it tepid souls should become fervent. 8. That by it fervent souls should be raised to a higher perfection. 9. That Christ would bless all houses in which the image of His Sacred Heart was set forth and honoured. 10. That he would give to priests devoted to the Sacred Heart the power of melting the most hardened hearts. 11. That those who spread abroad this devotion should have their name indelibly written upon the heart of their Saviour!

Fortunately perhaps for the world and for herself, from the time of her "revelation" the health of Marguerite Alacoque failed rapidly. She was never free from a burning pain in her side, which on Fridays was increased to agony. When she knew that she was dying, with the ecstatic fervour of stronger days she implored the nuns not to attempt to alleviate her anguish, saying that "the last moments of suffering were only too precious to her, and that she had still the longing which had always possessed her of living and dying upon the cross." She died October 17, 1690, in her forty-third year, and the eighteenth of her religious profession. Her last words were - "I have now nothing left to do, but to lose my breath in the Sacred Heart of Jesus."

The first important disciple of Marguerite Alacoque was her correspondent La Colombière, who believed that her message was of heavenly origin, and solemnly consecrated himself to the devotion of the Sacred Heart. In 1678 she had the happiness of hearing that, in the Monastery of the Visitation at Moulins, the worship of the Sacred Heart had commenced, though at Paray it was not inaugurated till six years after her death. In 1697 Queen Mary Beatrice, then exiled in France, was persuaded by the Jesuits to implore the Papal authority to institute a festival in honour of the "Sacred Heart of Jesus;" but her petition was rejected, and authority for the "Adoration of the Sacred Heart" was only obtained in 1711 from Clement XI. Yet meanwhile, by the indefatigable exertions of the Jesuits, the "devotion" had already become most popular, and the extraordinary dimensions it has assumed since then are such that there is now scarcely a cottage or a room in a humble inn in France or Italy which is not decorated with a common gaudy print of the "Sacred Heart of Jesus." On August 23, 1856, an apostolic decree of Pius IX. made the fête of the "Sacred Heart" obligatory upon the whole Catholic Church. For a time it seemed as if the wish of Marguerite Alacoque was to be fulfilled, and that she herself was to remain forgotten, while the doctrine for which she had laid down her life was received everywhere. But her convent companions, seeing how great, though subtle, her influence had been, watched over the grave where she was laid, and in 1703 her tomb was opened and her body enclosed in an oak coffin. When the sisterhood were expelled from their convent at the Revolution of 1792, they took her bones with them, and for some time they were concealed in the paternal home of one of the sisters at La Charité sur Loire. It is interesting, however, that, even during the dispersion, the nuns regularly assembled in the deserted chapel at Paray on the day and hour of her death, to sing hymns in her honour. After their return, bringing back the body of Marguerite, the Bishop of Autun was induced to allow an inquiry to be instituted into the life and miracles of "the servant of God." Three alleged miracles out of many were selected for strict investigation, all being instantaneous cures of nuns from shocking internal disorders upon touching her bones! The examination proved satisfactory, and in 1824, Leo XII. saluted Marguerite-Marie by the title of Venerable; in 1863 Pius IX. gave her the additional honour of Beatification; her canonisation is still to come.

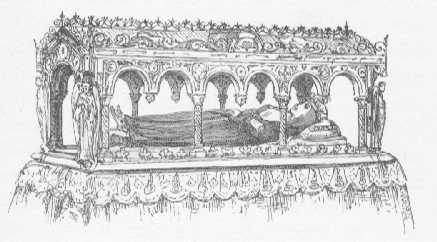

SHRINE OF MARGUERITE-MARIE ALACOQUE.

Paray in its present state is one great shrine to Marguerite-Marie Alacoque. It exists by the pilgrimages in her honour. Half its houses are inns or lodgings for the pilgrims. Two-thirds of its shops are for the sale of medals, prints, or biographies of La Bienheureuse. Its grand old romanesque church - La Paroisse - stands by the river side with two tall towers on either side of the gable of its west front, and, at the east end, a great apse diverging into a whole succession of little apses. Inside, it is a noble cruciform round-arched church, pure and beautiful. The only peculiar feature is the magnificent ancient font, now used as a bénitier, and surmounted by a crucifix. All around in groups, and behind the high altar in masses, are the banners offered to the “Sacred Heart of Jesus," chiefly of white satin, fringed and embroidered with gold. Some of these are from towns, some from Congregations in Paris, but by far the greater number from small country parishes - painfully and laboriously contributed by peasants, chiefly Bretons. The clean but rugged street winds up the hill to a picturesque old town-hall and the quaint tower of St. Nicholas; but it is only a few steps from La Paroisse, between shops full of rosaries and relics, to the iron grille which screens the Church of the Visitation. This is the sanctum sanctorum. It is covered with colour and gilding. Day as well as night numberless candles blaze ceaselessly around the shrine. Against the walls hang ranges of banners even more splendid than those we have already seen. That of Alsace, adorned with a cross, and the motto "In hoc signo vinces," is hung with crape. Over the altar is a modern picture of the event which is supposed to have taken place so often on that very spot, the appearance of Our Saviour to Marguerite-Marie. Beneath lies her body in a golden shrine beautifully decorated with enamel. It is dressed in the habit she wore in life, and is formed from the still-perfect bones, enclosed in a waxen image. One portion of the actual flesh is believed to remain intact; it is that portion of the head which is supposed to have rested, like that of St. John, on the bosom of the Saviour. The shrine of Marguerite, as it is now, almost forms the altar, and thus, as one of her poor devotees said, "The grave of the Bienheureuse serves as a pedestal for the Throne of the Sacred Heart."

The convent adjoining the chapel is little changed from the days when Marguerite-Marie inhabited it. The corridors have been painted by the nuns with scenes from her life. The Chapter-House remains where she was so often questioned about her visions, and the Infirmary where she died. In the garden we may still see the group of walnut-trees where she is affirmed to have laid her head upon the bosom of her Saviour, and the little "Chapel of the Apparition," erected on the spot where her heart is supposed to have been inflamed by actual contact with the Sacred Heart of her devotion.

As we sate in the chapel, one group of pilgrims after another came in, and approached the shrine upon their knees and kissed with reverence the relics, and murmuring voices repeated one of the authorised collects of the Beatified: - "O Lord Jesus Christ, who hast revealed in a wonderful manner to the Blessed Virgin Marguerite the impenetrable riches of Thine heart; grant, that by her merits and her example, loving Thee in all and above all, we may become worthy to dwell eternally in the same Sacred Heart."