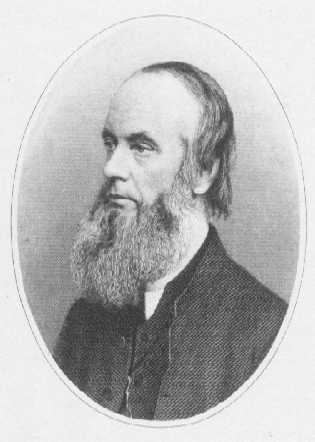

HENRY ALFORD

I HAVE been asked to write some memorial of my dear friend Dean Alford. The remembrance of his strong personality is ever present with me. I can hear his genial voice still, and feel myself carried away by his enthusiasm for all things good and beautiful; and yet, in gathering up the fragments that remain, there is not much to be told. He was one of those who always poured out his best thoughts in books, not in his letters, which are neither graphic nor characteristic. Of his published works there is a perfect library. Outside them, he had only his personal existence, infinitely loving and lovable; replete with tenderest care for others and utter indifference about himself; full of little peculiarities, which, to those who loved him, had their own charm as being his. What chiefly strikes one on looking back is, that no one had a more vigorous sense of enjoyment than Dean Alford, or more power of diffusing it; whether in the old Deanery, under the shadow of his own glorious cathedral, or in thymy uplands of the Roman Campagna, or amid the grand purple precipices of the Maritime Alps, his companions were equally carried away by it.

Henry Alford was born in London on October 7, 1810, being the son of the Rev. Henry Alford and his wife, Sarah Eliza Paget (daughter of a Tamworth banker), who died four months after the birth of her only child. His earliest amusement was to write books, and he became the author of "The Travels of St. Paul, from his Conversion to his Death,” - illustrated - at six years old.

As curate of Steeple Ashton in Wiltshire, and afterwards of Wraxall near Bristol, his father was his constant companion and friend. Henry Alford portrays their intimate relationship in the "School of the Heart" -

“Evening and Morning - those two ancient names

So link'd with childish wonder, when with arms

Fast wound about the neck of one beloved,

Oft questioning, we heard Creation's tale, -

Evening and Morning brought to me strange joy."

In 1817 the father went abroad with Lord Calthorpe, and Henry, at seven years old, was sent to school at Charmouth. After returning to England in 1818, his father took the curacy of Drayton, which was only a mile from Heale House in Somerset, where his elder brother, Samuel, lived with his numerous children, who were like brothers and sisters to the little Henry.

In 1824 Henry Alford was sent to Ilminster School - a gentle, delicate boy, with wondrous powers of memory, of unusually serious thoughts, which found minute expression in the self-examination of his journal, or in letters of meditative piety and advice addressed to his cousins at Heale. His school companions never lost the impression that he was a genius, with a natural talent for everything. "His mind was always poetical and imaginative, loving scenery, flowers, and whatever constituted beauty in nature and art. He was humorous and witty, with a quick sense of whatever was ludicrous and amusing, and was ready to get pleasure out of the least thing." Above all, his school companions always retained the impression of the extraordinary purity of his boyish life. One of them well remembers his saying in early years, when speaking of the titles given to our Saviour, that he liked to call him "Jesus, my Master." [1]

In the summer of 1827, Henry Alford left Ilminster to go to a tutor at Acton in Suffolk. This tutor was the Rev. John Bickersteth, under whose influence his religious tendencies developed. On November 18, 1827, he wrote in a Bible, "I do this day, as in the presence of God and my own soul, renew my covenant with God, and solemnly determine henceforth to become His, and to do His work as far as in me lies." As the time of going to Cambridge approached, he trembled before the temptations which were sure there to assail him. To one of his cousins he wrote: -

"You Cannot think how I dread Cambridge; I quite shrink from the thought of going there, and fear I shall fall. I have no Stamina as yet of religious principle, at least so I fear, and all as yet is talk and pride. People want me to get into the first class at Trinity. I hope I shall be enabled to do my best as in the sight of God, and not to regard the praise or dispraise of men, and then, if I fail of my object of attainment of earthly honours, I can be calm and contented under the will of my Heavenly Father."

Settled at Trinity, he was soon deep in lectures and enjoying all his classical studies, but finding nothing "satisfying" except the Bible.

"I read Æschylus and Homer," he says, "and then turn to Isaiah and Joel; and the heathen poetry, sublime as it is in itself, is mere prose in comparison. I read Algebra and Euclid, and then turn to the Epistle to the Romans, and all the reasoning of ancients and moderns appears weak and inconclusive; every store of spiritual and intellectual knowledge is hid in that divine book."

His letters lack the simplicity of youth, and are full of moral reflections. After apologising for this in a letter to his cousin, Fanny Alford (June 16, 1829), he says: -

"I cannot help it. It seems natural to my mind to think on things which are going on around me, as if they carried an instruction with them, and were meant in some measure to bear a secondary meaning, and teach a lesson of spirituality and heavenly-mindedness."

To Walter Alford he wrote from Cambridge in the following October: -

"It is not so much the gross outward temptations of this or any other place that I have to fear; my inmost feelings recoil and turn with disgust from the brutality and sensuality of many men whom I see around; but it is the insidious undermining, if I may say so, which study and literary habits carry on against the work of God in the soul; it is the springing up of those seeds of pride which an enemy hath sown in my heart, and which are working slowly, hut I fear surely, towards maturity - the pride of intellectual, philosophical, or classical acquirements - it is these I have to dread. Oh, the chilling influence of literary pursuits and literary society!"

He wrote also of the temptations which he felt from "being constantly brought into contact with men who live without God in the world, and in being surrounded with professors of religion, many of them neither moral nor religious."

In leisure moments, Henry Alford often occupied himself in translating favourite passages in the classics for his cousins, and urging them to compare them with still nobler passages in the Scriptures. "You cannot think how beautiful it is," he wrote, ''to select and admire the sublimest and finest parts of the classical philosophers and poets, and then to find parallel passages in Scripture, as may almost always be done, and comparing them; not to destroy the beauty of the former, but to exalt and bring into light the divine sublimity of the latter."

His chief college friendships seem to have been with Arthur Hallam, Tennant, and Alfred Tennyson. Writing of Alford's college life, Dean Merivale says: -

"I really think he was morally the bravest man I ever knew. His perfect purity of mind and singleness of purpose, seemed to give him a confidence and unobtrusive self-respect which never failed him. Then, as throughout his career, he was singularly remarkable for the versatility of his talents. If one of the friends among whom he was then held in estimation was more eminently gifted in verse, another more deeply plunged into the dark profound of juvenile metaphysics, a third promising to take higher rank in classics, a fourth in mathematics, Alford could at least hold his own with all of them, could appreciate all, could sympathise with all, and could gain in return the sympathy of all."

In 1831 Henry Alford's habits of self-examination increased to what many would feel to be a very unwholesome extent. In the words of Bishop Beveridge he wrote, "My very repentance wants repenting of; my holiest acts want purifying afresh in the blood of Christ."

“Even the Love of Him

Now mingled in my bosom with all sounds

And sights that I rejoiced in - and in hours

Of self-arraigning thought, when the dull world,

With all its saws of heartlessness and pride,

Came close upon me I approved my joys

And simple fondnesses on trust that He

Who taught the lesson of unwavering faith

From the meek lilies of green Palestine,

Would fit the earthly things that most I loved

To the high teaching of my patient soul.

And the sweet hope that sprung within me now

Seemed all-capacious, and from every source

Apt to draw comfort." [2]

Meantime he worked tremendously hard. "In those days he almost seemed to do without sleep," wrote one of his intimate friends and companions. In January 1832 he was announced thirty-fourth wrangler, eighth in the first class of the classical tripos. In the preceding year his father had married again, a Miss Susan Barber, whom he cordially welcomed as stepmother; and immediately after taking his degree he became himself engaged to his cousin, Fanny Alford of Heale.

"In their summer walks amid the woods and terraces of Burton," wntes Mrs. Alford, "and on the heights above Sedgmoor, the betrothed cousins framed for their future life no more ambitious scheme than the care of some country parish. They learned to open their hearts unreservedly to one another; they read, learned, and reasoned on Scripture together, and prayed together; they formed, and very nearly accomplished, in those six weeks, the design of reading together the first volume of Dobson's edition of Hooker's works, his first five books of 'Ecclesiastical Polity,' and his sermon on 'The Certainty and Perpetuity of Faith in the Elect.' Archdeacon Evans's charrning book, 'The Rectory of Valehead,' was twice read through, first by Henry alone, then by him to his future wife and her sisters. The good Archdeacon had been his tutor at Cambridge, and exercised great influence over his mind at that time. Henry determined to enable his future wife to read the New Testament in Greek, and for this purpose began a Greek Grammar in the form of a series of letters to her, which grew to the extent of sixty folio pages. For the amusement of his cousins generally he wrote some small pieces entitled 'Guesses at Truth,' &c., and gave them as his contribution to the 'Family Mirror,' a periodical which never attained the dignity of appearing in print, but was circulated in manuscript among various young members of the Alford family. In the enthusiasm of those young days he planned the formation of a society amongst ourselves for the regulation of social intercourse, with the object of avoiding frivolous conversation and giving mutual aid in detecting and correcting faults."

The beauties of Nature, then as always, were his greatest delight: -

“Beauty and Truth

Go hand in hand - and 'tis the providence

Of the great Teacher, that doth clearest show

The gentler and more lovely to our sight,

Training our souls by frequent communings

With her who meets us in our daily path

With greetings and sweet talk, to pass at length

Into the presence, by unmarked degrees,

Of that her sterner sister best achieved

When from a thousand common sights and sounds

The power of Beauty passes sensibly

Into the soul, clenching the golden links

That bind the memories of brightest things." [3]

And especially delightful to him was the scenery of the hill-ridges above Sedgmoor: -

"I would stand

Upon the jutting hills that overlook

Our level moor, and watch the daylight fade

Along the prospect; now behind the leaves

The golden twinkles of the western sun

Deepened to richest crimson; now from out

The solemn beech-grove, through the natural aisles

Of pillared trunks, the glory in the West

Showed like the brightly burning Shechinah,

Seen in old times above the Mercy-seat

Between the folded wings of Cherubim."

Returning to Cambridge in October 1832, Henry Alford took pupils, and in the following spring published his "Poems and Poetical Fragments." In October 1833 he was ordained at Rochester, and entered upon the curacy of Ampton. which his father had vacated to take the rectory of Winkfield. Many misgivings beset him at first as to how he could fulfil his clerical duties. "My inexperience may be in a few years remedied," he wrote to his betrothed wife soon after, "but I feel as if I had no ground to go upon. My fancied fitness for the ministry and my cherished schemes of usefulness have all slipped away, and I am left a mere boy in understanding." And again, after he had been seven weeks at Ampton, "Oh, how the profession of God's ministry and the light of His countenance bring to notice all my many shortcomings, and set before me my secret sins. On November 6, 1834, his journal records: -

"I went up to town and received the Holy Orders of a Priest; may I be a temple of chastity and holiness, fit and clean to receive so great a guest; and, on so great a commission as I have now received, O my beloved Redeemer, my dear Brother and Master, hear my prayer."

In March 1835 the small, obscure, and till then neglected vicarage of Wymeswold in Leicestershire, fell vacant, with its population of 1200 and an income of £120, and was accepted by him with a view to his immediate marriage with his cousin Fanny, "that dear person, who had been through life the chief object of his love on earth." At Wymeswold he built and superintended the schools, he almost rebuilt the church, and conducted three services every Sunday. He also began to preach the unwritten, though much meditated, sermons for which he afterwards became celebrated. The narrow income of his living necessitated taking pupils, but the extra labour thus involved rendered only more delightful his holiday rambles with his wife, especially their first foreign tour in 1837, described in his Sonnets, which at this time go far to form a record of his life. Of the quiet happiness of his home life he tells us in "Every Day's Employ:” -

"I have found Peace in the bright earth

And in the sunny sky:

By the low voice of summer seas,

And where streams murmur by.

I find it in the quiet tone

Of voices that I love:

By the flickering of a twilight fire,

And in a leafless grove.

I find it in the silent flow

Of solifary thought:

In calm half-meditated dreams,

And reasonings self-taught.

But seldom have I found such peace

As in the soul's deep joy

Of passing onward free from harm

Through every day's employ.

If gems we seek, we only tire,

And lift our hopes too high;

The constant flowers that line our way

Alone can satisfy."

During the residence of the Alfords at Wymeswold their four children were born, and there, in April 1844, their youngest boy, Clement, died. "Is not the triumph of having one dear child landed in glory enough to comfort the heart even of bereaved parents?" the Vicar wrote to his brother-in-law, Walter Alford.

In 1845 the design of writing a commentary on the Greek Testament had begun to assume a definite form in Henry Alford's mind. He fancied at first that it could be accomplished in a twelvemonth of hard labour; but 1847 found him only advanced sufficiently to have an increasing sense of the importance and magnitude of the work he had undertaken; and after a visit to Bonn in that summer for the sake of German study, he resigned his pupils - having trained as many as sixty, of whom many have since filled conspicuous positions - and gave up to his commentary all the time which was not claimed by his parish. Yet in the fullest sense he fulfilled his parochial duties. Mrs Alford writes: -

"It was his habit to enter thoroughly into the individual cases of his pastoral work. Some portion of it was necessarily intrusted to his curate, and he took great pains to secure colleagues of congenial spirit with himself. Each soul was treated distinctly as a part of the charge committed to him. Though naturally disposed to be reserved and shy, Henry did not seclude himself from personal intercourse with any of his parishioners if it might be profitable for them. Privately - as well as publicly his gentle and winning sympathy was ready to be offered to each one who sought it, whether in joy or sorrow. Nor did he omit to take any suitable opportunity that presented itself to him either of correcting or of encouraging those whom he desired to see walking in the way of godliness."

His standard of what he required in a Curate is expressed in the following passage from a letter in which he asks help in seeking one: -

"I want him to teach and preach Jesus Christ, and not the Church; and to be fully prepared to recognise the pious Dissenter as a brother in Christ and as much a member of the Church as ourselves. Above all, he should be a man of peace, who will quietly do his own work and not breed strife."

In November 1850 the first volume of the Greek Testament was published. Alford had thrown his whole soul into it. "His bravery," says Dean Merivale, "was manifested in the unfailing serenity and confidence with which he encountered his work, and the cheerful, undoubting satisfaction with which he looked both forward and backward. His mind seemed at perfect peace, as one well assured that his work was appointed him, and that he was doing it."

When working at Babbicombe at the second volume of his Greek Testament during his summer holiday in 1850, Henry Alford lost his remaining son, Ambrose. His memory was always a most precious possession to his parents. He had lived, to a rare degree, in the purest light of truth, and he died before the clear stream of his boyish life had mingled with the turbid waters of the world. The boy's danger was only apparent an hour before his death. There were few parting words, but those very sweet ones. His father records them -

"Refresh me with the bright blue violet,

And put the pale faint-scented primrose near,

For I am breathing yet:

Shed not one silly tear,

But when my eyes are set,

Scatter the fresh flowers thick upon my bier,

And let my early grave with morning dew be wet.

I have passed swiftly o'er the pleasant earth,

My life hath heen the shadow of a dream;

The joyousness of birth

Did ever with me seem:

My spirit had no death,

But dwelt for ever in a full swift stream,

Lapt in a golden trance of never-failing mirth.

Touch me once more, my father, ere my hand

Have not an answer for thee; - kiss my cheek

Ere the blood fix and stand

When flits the hectic streak;

Give me thy last command,

Before I lie all undisturbed and meek,

Wrapt in the snowy folds of funeral swathing-band."

In a paper written nearly twenty years afterwards, Henry Alford describes no imaginary scene, but his boy's death-bed on the last day of August.

"You remember when we last entered such a chamber; and on that little press-bed in the corner by the window lay all we cared for; in that room we scarce dared breathe; even grief was lulled, and all was solemnised without a feeling beyond. We stood all four round his dying bed, with the sunset from the western sea filling the room with rosy light; and we watched till the dear features lost meaning and their lines stiffened; and then I pressed down the eyelids, and we left Mama with him, and we three went out bewildered, and sat down on the beach, and I said, 'Where is he now?' The sun had gone down, and had left in the lower sky a few lines of dull red, and under them the sea looked a pale ghostly blue, and the sky above was clear, yet without a star. And there was not a sound, not a breath, not a ripple. All seemed to speak of a presence gone. He had been about those rocks, and on that beach, and cleaving those waters - and now?"

Long after, writing from Devonsliire to his daughter Mary, Henry Alford says: -

"July 17, 1866. - The journey was long enough. After passing Exeter came the well-known line of red coast and the accustomed pang and tears in the eye as a certain bay of sorrow came in sight. Sixteen years ago! O darling! what would he have been now? Yes, but what is he now?"

It was in the old paternal house of Heale, which had witnessed their betrothal and marriage, that the bereaved parents sought a refuge in their grief. Its desolation and decay were congenial to them.

"We are at our childhood's home, a large old house 'in one of the beautiful sites in the county of Somerset. Everything here is hushed and solemn. The house is one of the last century, and part of no one knows how many centuries before. The timber is vast and untrimmed, the boughs waving before and scraping the windows. The front looks up a decayed avenue of chestnuts yearly despoiled of some of their companions, at the end of which is a tall column erected by the great Lord Chatham to the memory of Sir William Pynsent, who bequeathed him the estate of Burton Pynsent, now all gone to ruin, the house fallen down, the garden a wilderness. Add to all this that my wife's father, the head of our family, is paralysed and helpless, waiting his dismissal. In this place we have all grown up and played our childish games, and now it is the centre and resort of the widely scattered members of a family numbering twelve married couples and thirty grandchildren, besides brothers and sisters of the last generation - in all numbering sixty-two persons. Is it not a place strangely in harmony with our present feelings? 'This is not your rest' is written on every mouldering stone of the old house; and to add to all, dear Ambrose was here full of life and spirits only a month ago."

Afterwards, writing to Lady Sitwell, Henry Alford said: -

"I have found that the fact of our dear children having wrestled with and overcome death seems more than ever to remove all terror from the prospect of our own struggle with him. To think that those cherished ones, from whom we have carefully fenced off every rough blast, whom we led by the hand in every thorny path, have gone by themselves through the dark valley; that those weapons of which we had only begun to teach them the use have been successfully wielded by their little hands, and that their victory is gained before it had come to our own turn to prove them. Such thoughts seem to show us the meaning of the wonderful expression, 'More than conquerors.' If they could struggle and overcome, much more we, with so much more knowledge and experience. No doubt our fight will be harder, for the world has wrapped itself more closely round our hearts. But let not our faith fail in Him who has conquered death, and I do not doubt that He who now leads our dear children in the green pastures of eternal joy will in His own time make perfect His strength in our weakness, and show us that all deep afflictions have been in reality our best and greatest blessings."

In 1851-52 Henry Alford was frequently employed as a lecturer, and his lectures, many of which were repeatedly delivered, became very popular. One of them, "The Queen's English," was afterwards published as a little volume. In the autumn of 1852 he watched over the death-bed of his father, his best and earliest friend, the friend whom he always felt to have understood him best. In the following spring came the offer of Quebec Chapel in London, and he determined to leave Wymeswold. To his wife, on receiving the offer, he wrote: -

"I feel deeply that my work at Wymeswold is done; it has been the work of a pioneer. I have been the means of preparing and working for what is to come; but, like all others who do this, I am not the man to continue it. Untoward circumstances have thrown me into false positions; and now that my Greek Testament withdraws me from the parish, I have, and must have to the people in general, the aspect of an idle shepherd, letting others do his work; and after eighteen years, as the generation grows up which knows not Joseph, this must infallibly get worse and worse. . . . First trust me, which I mention only first because it is in this matter the necessary inlet to the other, and next trust God. If we take up this plan, determined to serve Him, not neglecting common prudence, but at the same time, in a humble self-sacrificing spirit, He will bring us safe through, never doubt it; so let me at least have your sympathy. Eve wept over her flowers; Eve's daughter can do no less. Eve's son will have hard work to get up a dry parting; but sure I am of one thing - heaven's flowers will bloom the sweeter for it."

A letter to his daughter Mary about this time, on their future life, contains the following touching words: -

"In the life which is now opening may we be kept as a Christian family, without any difference or coldness to each other, and each be the means of good to the rest, as long as we are spared together here! I feel and know that I am often hasty and wayward to dear Alice and you, and that my manner and words discourage and grieve you. This is very sinful in me; and when you see it, you see that your father on earth is not like your Father in heaven, on whose brow there is never a frown, who never is wayward or hasty. Forgive it, and do not let it discourage you, dearest children. Pray for me, and I will strive to be gentle and loving at all times, and to reprove, not with temper, but with equity and mildness."

And again: -

“Half our little band is already with the Lord; let us ever so live as those hoping to join them where they are. They are one with Christ in glory; let us be one with Him and them in faith and hope and purity, living by one blessed spirit. Many and sweet are our comforts here, deep and blessed our love for each other, and what will our joy and love be when our circle is again completed, father and mother, brothers and sisters, in a glorious eternity!”

In September 1853 the Alfords removed to a house in Upper Hamilton Terrace, St. John's Wood, in a situation whose quietness was favourable to literary work, while the distance from Quebec Chapel was not too great for a walk. During the four years of his residence here, Henry Alford's habit was to rise at six, light his own fire in his study, and work there till one o'clock. One hour before breakfast was given to composing his sermons, and the rest of the morning to the Greek Testament. In the afternoon he visited amongst the poor inhabitants of his district, though the principal care of them devolved upon his curate. Evenings passed at home were spent in reading aloud to his family, and few read so well or effectively. His morning sermons were carefully written, and six volumes of these Quebec Sermons were published; but his afternoon sermons were extempore. Reading any of the sermons, however, is not what hearing them was. He had the manner and the voice which gave at once a solemnity and an interest to all he said; his hearers knew that he felt all he was saying to the uttermost, and his rich stores of knowledge of theology and literature of every kind made him especially acceptable to the cultivated classes who formed the main portion of his congregation.

Yet, people went to Henry Alford's church not for an intellectual feast, but to gain help in living the Christian life. He put forth the truths on which that life depends. He pictured the life itself and fearlessly exposed the faults and temptations by which a London existence, especially in fashionable London, is surrounded.

The afternoon sermons were rather a kind of exegetical lecture, embracing the whole context of a passage, and going fully into its connection and argument. Critical questions were often handled, though only as far as the subject in hand fairly demanded. This kind of preaching was then a novelty, though it has since become less uncommon, and the Sunday afternoon congregation at Quebec Chapel was consequently of a peculiarly high order - members of Parliament, eminent lawyers, and other varied representatives of the intellectual classes, to whom the study of a definite portion of the New Testament which was presented to them had an especial interest, as inviting them to verify what was said by the conscientious study of the chapter for themselves. It was known also that Alford was a careful scholar and a diligent student. Men went to him as to one who could render a reason, and who was not likely to rely on a mistranslation in the Authorised Version, either because he had not looked at his Greek Testament before he went into the pulpit, or because he would not have detected the error if he had. [4]

Of these lectures the Rev. E. T. Vaughan writes: -

"The work which Alford did in making these critical and exegetical helps, which had hitherto been the property in England only of a few readers of German, to become the common heritage of all educated Englishmen, was a work which no other man of his own generation could have achieved equally well, or was likely to have attempted. His industry was wonderful, his power of getting through work such as I have never known equalled. No man could sum up more clearly and concisely the conflicting opinions of others; none could, on the whole, exercise a fairer or more reasonable judgment between them. No man could be more honestly anxious to arrive at truth; he shirked no difficulty which he felt; he kept back nothing which he believed. On all critical and exegetical questions he was always open to conviction, and never ashamed to confess a change of opinion."

After having been some months at Quebec Chapel, Henry Alford wrote to his friend Mr. Vaughan: -

"The chapel is full, and the people seem attached and kind, and liberal in contributing to every good work. My morning congregation is, of course, the congregation, and for them I write my sermons, having begun with the year. But the afternoon congregation is the one I love best, being my own child. It has increased from absolutely nothing to within a hundred or two of the morning. To them I do not preach, but expound the Gospels; in fact, expand my Greek Testament notes, a sort of thing in which, as you may imagine, I delight much. My district work is very interesting, and when our schools are once set on foot, will be much more so. But my situation, you must know, is no sinecure. I find it difficult to get time for my Greek Testament work amongst its duties."

In the spring of 1854 the living of Tydd St. Mary's, Lincoln, was offered to Henry Alford by the Lord Chancellor Cranworth. He comically describes in his journal his visit to the Lord Chancellor on the occasion of his declining it: -

"When I asked to see Lord Cranworth, the servant said his master was engaged. I then said, 'I am not come to ask for anything, but to refuse something offered.' 'Oh, sir, then I am sure he will see you,' was the reply."

When wearied with the work of the London season, the summer tours of the Alfords in the Pyrenees, the South of France, and Scotland were the greatest refreshment. The family travelled in the simplest and most primitive fashion, Mrs. Alford and her daughters carrying their necessaries in hand-bags over the mountains, and the father of the family looking like a pilgrim of old time, and almost confining his luggage to a thick walking-stick, which unscrewed at different points, and disclosed comb, tooth-brush, &c. &c. In 1856 Henry Alford became one of the 'Five Clergymen' of the Clerical Club, who met for the purpose of revising the Authorised Version of the New Testament - of which the first publication - the Gospel of St. John - appeared in the spring of 1857. "In this work he soon won the affectionate esteem of his companions. Thoroughly versed in the subject, he was not in the least disposed to dogmatise, or press his own opinion unduly; he was quick in catching and appreciating the suggestions and arguments of others, even when they were at variance with his own. His opinion on difficult points of criticism, interpretation, and rendering was always received with respect; but in general he seemed to keep himself in the background." [5]

Alford's character in private at this time "was strongly marked," says Mr. Shaw, "by three qualities - earnestness, for his religion was no mere theory; manliness, for it never degenerated into sentimentalism; energy, for it abhorred all idleness of mind or body; his grasp of the truth he held was very tenacious, he never felt tempted to go from his anchorage." [6] One of those who knew him best wrote long afterwards concerning his life at this time: -

"His bravery was manifested in the unfailing serenity and confidence with which he encountered his work, and the cheerful, undoubting satisfaction with which he looked both backward and forward. I never heard a murmur from him, I never saw him despond, I never knew him look anxiously about for the means of bettering and advancing himself. His mind seemed at perfect peace, as one well assured that his work was appointed him, and that he was doing it. I knew many of his troubles, but this brave spirit of his, anchored in domestic love and religious faith, never quailed before any of them."

In March 1857, whilst he was engaged with his family in receiving a drawing-lesson from Leitch the artist, a letter came from Lord Palmerston offering him the Deanery of Canterbury, an offer which came just when he was feeling especially overdone with work, and which he hailed gladly, as giving him the time sorely needed for his Biblical studies, as well as for attending the meetings of the Ecclesiastical Commission, of which he was an official member, and of the Lower House of Convocation of the Province of Canterbury, of which, after the Prolocutor, he was the senior member.

IN THE DEANERY GARDEN, CANTERBURY.

Great too was the delight of his art-loving soul in his new home, in the charming old house and ancjent garden, with its time-honoured mulberry-trees, nestling under the shadow of one of the grandest cathedrals in the world.

By the establishment of an afternoon sermon in the cathedral Dean Alford was able to carry out, in some measure, the work for which he had seemed so peculiarly fitted at Quebec Chapel. During his sermons the cathedral was crowded. Few Churchmen, certainly few Churchmen in high places, had ever dared to speak before with his fearless liberality. His position towards the great Nonconforming communities was almost unique. "True to the traditions of his cathedral," said Archbishop Tait, "which offered a sanctuary in time of danger to the persecuted Protestants of the Continent, he was enabled, from his longing after perfect communion with all who served his Lord, to unite with many from whom others are by conscientious convictions separated, and to make it understood that the faithful minister and leader of the Church of England has a heart as wide as the Church of Christ." [7] After one of his sermons a poor woman was heard to say, "And the common people heard him gladly."

In everything the change from London to Canterbury was for the happiest. By the older inhabitants of the Precincts the Dean was at first looked upon as a revolutionist, but the gentleness of his character disarmed opposition. Work of the most interesting kind could now also frequently be varied by tours which were full of interest, and which afforded him delightful opportunities for the sketching which was his greatest enjoyment, and in which he became a facile though never a distinguished artist. Above all, he was able to finish the great work of his life, concerning which he thus touchingly expressed his hopes: -

"I have now only to commend to my gracious God and Father this feeble attempt to explain the most mysterious and glorious portion of His revealed Scriptures; and with it this, my labour of now eighteen years, herewith completed. I do it with humble thankfulness, but with a sense of utter weakness before the power of His Word, and inability to sound the depths even of its simplest sentence. May He spare the hand which has been put forward to touch the Ark! May He, for Christ's sake, forgive all rashness, all perverseness, all uncharitableness, which may be found in this book, and sanctify it to the use of His Church; its truths, if any, for teaching; its manifold defects for warning. My prayer is and shall be, that in the stir and labour of men over His Word, to which these volumes have been one humble contribution, others may arise and teach whose labours shall be so far better than mine, that this book and its writer may ere long be utterly forgotten."

The close of 1860 finds in the Dean's journal: -

"I am now writing with the ten midnight bells ringing in 1861. God be praised for all the mercies of another happy year, in which I have been enabled to finish my Greek Testament, the work of eighteen years. May He grant that future years, if I am spared to see any, may be spent more to His praise! If I am to live, keep me with Thee; if I am to die, take me to Thee !"

In the following spring the Dean paid his first visit to Rome, seeing and enjoying much, and obtaining leave from Cardinal Antonelli to spend several mornings in the study of the Codex Vaticanus, making facsimile copies of all the principal various readings. Yet he returned to England full of bitterness at the impurity of faith in Rome - in whom "was found the blood of all the saints from Ignatius to the Waldenses," - and feeling that, with regard to external Rome, after a month one only begins to see what there is to see." In 1863 he went back to Rome for the winter, taking his wife, a niece, and his youngest daughter with him; his elder daughter had been married in the preceding year. On this occasion he was even more strongly impressed with the ignorance and superstition of the lower orders in Italy - "their whole creed and practice being pagan."

The completion of the second volume of the "New Testament for English Readers," and his editorship of the Contemporary Review, were among the heavier of the Dean's next few years at Canterbury. The preparation and publication of his "Family Prayers," his "Year of Praise," and many articles in Good Words were amongst their lighter occupations. His hymns, one of which has become the Baptismal Canticle of the English Church, were always a great source of enjoyment to him. The chief events of his home life were the marriage of his youngest daughter, the birth of two granddaughters, and his renting on a long lease a small country-house, Vine's Gate, half-way up Toy's Hill from Brasted, commanding a view down a wooded glen over Lord Amherst's and Lord Stanhope's parks, and away as far as Sevenoaks. He took this place partly with the view of providing himself with a home in case of infirmities unfitting him for work, in which case he had decided to resign his Deanery. Always averse to the dignities of his position, he relaxed them altogether at Vine's Gate, carrying out especially one of his pet peculiarities, which made him rebel against wearing stockings at all, or even shoes, except out of doors, and then of the merest sandal description.

HENRY ALFORD, DEAN OF CANTERBURY

Those who saw much of the Dean in these years of his Canterbury life retain a most vivid recollection of his conversational charm, as well of his own facility of expression, never at a loss for a word, and the best word, to express his meaning, as of his wonderful power of drawing out the best points in others, and the intensity of his sympathy. Vividly also do they recall the exquisite pathos as well as humour of his readings aloud, and his facility in passing from one subject to another, throwing himself with equal eagerness - his whole being - into the one which was arresting his attention at the time. This was especially the case on serious questions. "As in his writings on great subjects, so in his conversation respecting them, there was a wholeness of heart, a unity of spirit, resembling 'the cloud which moveth altogether if it moveth at all.'" [8] In all his words, as in all his acts, his extreme largeness of heart was manifest. "So you cannot conceive," he wrote to a niece, "how one who denies the Atonement in our sense can receive the Holy Communion with earnestness; but I can. Unitarians, I think, often beat us in their intensely 'thankful remembrance of Christ's death,' regarding it as the great central act of love, though not in the sense we do." His own perfect faith at this time is touchingly shown in his lines on "Life's Answer:” -

"I know not if the dark or bright

Shall he my lot:

If that wherein my hopes delight

Be best or not.

It may be mine to drag for years

Toil's heavy chain:

Or day and night my meat be tears

On bed of pain.

Dear faces may surround my hearth

With smiles and glee:

Or I may dwell alone, and mirth

Be strange to me.

My bark is wafted to the strand

By breath divine:

And on the helm there rests a hand

Other than mine.

One who has known in storms to sail

I have on board.

Above the raging of the gale

I hear my Lord.

He holds me when the billows smite,

I shall not fall:

If sharp, 'tis short; if long, 'tis light;

He tempers all.

Safe to the land, safe to the land,

The end is this:

And then with Him go hand in hand

Far into bliss."

It was typical of his character that, whenever any one took a walk with Dean Alford, he outwalked them. He could not loiter. His rapidity in everything was extraordinary - much too extraordinary. This was especially the case with his rapidity of thought. He often regretted that, write as hard as he might, his pen could not keep pace with his ideas. But his most ardent admirers probably feel that he wrote too much and published too much. Had he been able at an earlier age to concentrate his attention on a few subjects, he might have attained in them to a far higher point of excellence. But he would always throw all his energies for a time into the subject on which he was engaged, and then turn to something else. Thus it is recorded in his Memoir that five of the hymns in his "Year of Praise" were composed on five successive days. He published everything good that he wrote.

FROM THE DEAN'S GARDEN, CANTERBURY.

The incessant restlessness of action produced by the Dean's activity of thought amounted to incapability of taking rest. It was a real misfortune to him that he had a natural talent for everything - far too many things to admit of his attaining perfection in any of them but in his humility about this he was always indescribably lovable. In his little home arrangements, whether carpentering, upholstering, painting, arranging, decorating, or gardening, he was not so much the planner and contriver as the head-workman. He was enthusiastically fond of music, and looked upon it as the expression of poetic thought. Often hasty, he was always generous; and though often ruffled by slight annoyances, he could bear any great trial with more than patient - with happy resignation.

In 1868 Dean Alford published an illustrated volume on the Riviera, to which he had paid repeated visits with ever-fresh enjoyment. Most intensely did he delight in the rich foregrounds of heath and arbutus and pines with which the forest-clad hills near Cannes abound, backed by the jagged line of the Estrelles, the most varied of all minor European mountain chains. At Monaco he "saw hell in all its vice, and listened to some splendid music.” On one of these southern tours he had written to his wife: -

"March 1866. - I am flitting away from home, a boy of fifty-seven, to enjoy a holiday a boy of twenty-five would despise. It all looks strange and bizarre, but far above it all is an atmosphere of calm sunny thankfulness, causing me to think and feel 'Not more than others I deserve, but God hath given me more.'"

In 1868 the Dean again went to the Riviera, visiting, on his return journey, Ars with its memories of its holy Curé Vianney, and afterwards describing it in articles in the Contemporary Review.

Early in 1870 the Dean entered into an arrangement for undertaking a Commentary on the Old Testament, to be completed in five volumes and in seven years, "if life were spared." At the same time he took a prominent part in the Committee for Biblical Revision, which began by Christians of all denominations kneeling and receiving the Communion together around the tomb of Edward VI. in Westminster Abbey. But his health was not now what it was. In the autumn he began frequently to complain of sleeplessness and oppression in the head and he returned from Vine's Gate to Canterbury in November 1870, with an expression in his journal of "gladness to get once more into the old place, and pleasure after his long hill solitude to see old faces once more" In December his physician pronounced his brain overworked, and that it must have total rest thus giving a death-blow to his most fondly cherished work.

A few days after he wrote to a niece: -

"After all you were right, and it was a rash act to undertake the Old Testament. The doctor has told me it is too late in life to enter on a new and laborious department of study. . . . As to being low about it I cannot see it so. If God's good hand has brought me to sixty in vigour, surely all after is pure gain, in whatever form it may please Him to shape it."

And to his eldest daughter: -

"My own view is, a man who has lived to sixty has so much cause for thankfulness, it ought to over-power every other feeling; so it has not occurred to me to be in low spirits. I shall now look up the colour-box and the garden-tools, and the fishing-rods of old days, and take up light literature once more."

But it must have been in the prescience that the blessing of his earthly presence would not long be with them that he had written to comfort his daughter afterwards the pathetic lines - "Filiolae Dulcissimae."

“Say, wilt thou think of me when I'm away,

Borne from the threshold and laid in the clay,

Past and forgotten for many a day?

Wilt thou remember me when I am gone,

Farther each year from thy vision withdrawn,

Thou in the sunset and I in the dawn?

Wilt thou remember me when thou shalt see

Daily and nightly encompassing thee

Hundreds of others, but nothing of me?

All that I ask is a gem in thine eye,

Sitting and thinking when no one is by,

'Thus he looked on me - thus rung his reply.'

'Tis not to die, though the path be obscure,

Grand is the conflict, the victory sure:

Past though the peril, there's One can secure.

'Tis not to land in the region unknown,

Thronged by bright spirits, all strange and alone,

Waiting the doom from the Judge on the throne.

But 'tis to feel the cold touch of decay,

Tis to look back on the wake of one's way

Fading and vanishing day after day.

This is the bitterness none can be spared:

This the oblivion the greatest have shared:

This the true death for ambition prepared.

Thousands are round us, toiling as we,

Living and loving, whose lot is to be

Passed and forgotten, like waves on the sea.

Once in a lifetime is uttered a word

That doth not vanish as soon as 'tis heard:

Once in an age is humanity stirred:

Once in a century springs forth a deed

From the dark bands of forgetfulness freed,

Destined to shine, and to help, and to lead.

Yet not e'en thus escape we our lot:

The deed lasts in memory, the doer is not:

The word liveth on, but the voice is forgot.

Who knows the forms of the mighty of old?

Can bust or can portrait the spirit enfold,

Or the light of the eye by description be told?

Nay, even He who our ransom became,

Bearing the Cross, despising the shame,

Earning a name above every name, -

They who had handled Him while He was here,

Kept they in memory his lineaments clear, -

Could they command them at will to appear?

They who had heard Him, and lived on His voice,

Say, could they always recall at their choice

The tone and the cadence which made them rejoice?

Be we content then to pass into shade,

Visage and voice in oblivion laid,

And live in the light that our actions have made.

Yet do thou think of me, child of my soul: -

That when the waves of forgetfulness roll,

Part may survive in the wreck of the whole.

Still let me count on the tear in thine eye,

'Thus he bent o'er me, thus went his reply,'

Sitting and thinking when no one is by."

At the beginning of 1870 the Dean wrote in his journal: -

"Sat up to the New Year. God be praised for all His mercies during the past year of great events. He only knows when my course will end. May its evening be bright and its morning eternal day. . . . God only knows whether I shall survive this year. I sometimes think my health is giving way, but His will be done."

The New Year's day of 1871 was a Sunday. He preached extempore in the cathedral as usual in the afternoon. Notes taken down at the time record that he said: -

"The secret of the peacefulness with which the Psalmist went each night to rest, undisturbed by the cares of the past day or fears for the morrow, is answered in the verse - 'For the Lord sustained me.' . . . While we heartily thank God for His goodness to us in times past, let us pray to Him still to guide our steps during the year which has just begun, without longing too anxiously for the gratification of our own particular wishes, which must be short-sighted, and may be wrong. . . . It is not for us to consider how many of those present will meet together here next New Year's Day, or what public events may then have taken place. Our duty is only to trust wholly in God's love, casting all our care upon Him, for He careth for us, and to strive earnestly to become less and less unworthy of His love and care."

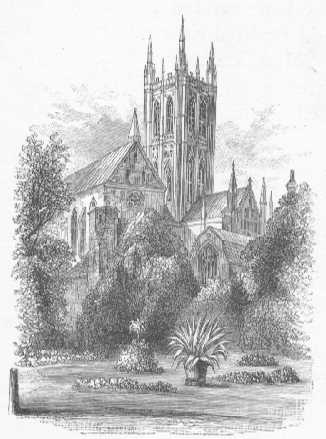

ST. MARTIN'S, CANTERBURY.

In the following days the Dean suffered much from the severe cold to which he was exposed while attending meetings for the establishment of a Relief and Mendicity Society in Canterbury, but on the 6th he was able to entertain a large dinner-party. On Sunday the 8th he was able to assist in the Holy Communion and to preach, but on the following days he was less well, and on the morning of the 12th, when even his nearest neighbours had only just heard that he was unwell, the passing bell of the cathedral announced that the Deanery was desolate.

Painlessly and peacefully he had passed into the better life. Truly for him, in his last moments, was the petition in his own hymn answered: -

"Jesus, when I fainting lie,

And the world is flitting by,

Hold up my head:

When the cry is, 'Thou must die,'

And the dread hour draweth nigh,

Stand by my bed!”

That hymn and another of his own were sung at his funeral. He rests beneath the yew-trees in St. Martin's Churchyard, on the slope of the hill just outside Canterbury. There, where the first English queen built her little chapel, and where Augustine baptized the first Christian king, the dear Dean Alford is buried. His tomb, by his own written desire, bears the inscription -

“Deversorium viatoris Hierosolymam proficiscentis."

[1] Letter from America. Memoir, p. 492.

[2] From "The School of the Heart."

[3] From ''The School of the Heart."

[4] Memoir. Letter of B. Shaw, Esq.

[5] Memoir. Letter of Rev. W. G. Humphry.

[6] See Memoir, p.497.

[7] See the Archbishop's Charge, Octoher 2, 1872.

[8] Memoir. Reminiscences of Rev. Dr. Stoughton.