VII

OXFORD LIFE

A few souls brought together as it were by chance, for a

short friendship and mutual dependence in this little ship of

earth, so soon to land her passengers and break up the company

for ever." - C. KINSGLEY.

To thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night

the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man." -

SHAKSPEARE, Polonius to Laertes.

"If you would escape vexation, reprove yourself liberally

and others sparingly."-CONFUCIUS.

IT was the third year of our Oxford life, and Milligan and I

were now the "senior men" resident in college ; we sat

at one of the higher tables in hall, and occupied stalls in

chapel. We generally attended lectures together, and many are the

amusing tricks I recall which Milligan used to play-one

especially, on a freshman named Dry - a pious youth in green

spectacles, and with the general aspect of "Verdant

Green." An undergraduate's gown is always adorned with two

long strings behind ; these strings of Dry, Milligan adroitly

fastened to mine, and, inventing one excuse after another, for

slipping round the room to open the door, shut a window, &c.,

he eventually had connected the whole lecture in one continuous

chain; finally, he fastened himself to Dry on the other side; and

then, with loud outcries of "Don't, Dry, - don't, Dry,"

pulled himself away, the result being that Dry and his chair were

overturned, and that the whole lecture, one after another, came

crashing on the top of him! Milligan would have got into a

serious scrape on this occasion, but that he was equally popular

with the tutors and his companions, so that every possible excuse

was made for him, while I laughed in such convulsions at the

absurdity of the scene, that I was eventually expelled from the

lecture, and served as a scapegoat.

I think we were liked in college - Milligan much better than

I. Though we never had the same sort of popularity as boating-men

and cricketers often acquire, we afforded plenty of amusement.

When the college gates were closed at night, I often used to rush

down into Quad and act "Hare" all over the queer

passages and dark corners of the college, pursued by a pack of

hounds who were more in unison with the general idea of Harrow

than of Oxford. One night I had been keeping ahead of my pursuers

so long, that, as one was apt to be rather roughly handled when

caught after a very long chase, I thought it was as well to make

good my escape to my own rooms in the New Buildings, and to

"sport my oak." Yet, after some time, beginning to feel

my solitude rather flat after so much excitement, I longed to

regain the quadrangle, but knew that the staircase was well

guarded by a troop of my pursuers. By a vigorous coup d'état

however, I threw open my "oak," and seizing the

handrail of the bannisters, slipped on it through the midst of

them, and reached the foot of the staircase in safety. Between me

and the quadrangle a long cloistered passage still remained to be

traversed, and here I saw the way blocked up by a figure

approaching in the moonlight. Of course it must be an enemy!

There was nothing for it but desperation. I rushed at him like a

bolt from a catapult, and by taking him unawares, butting him in

the stomach, and then flinging myself on his neck, overturned him

into the coal-hole, and escaped into Quad. My pursuers, seeing

some one struggling in the coal-hole, thought it was I, and flung

all their sharp-edged college caps at him, under which he was

speedily buried, but emerged in time to exhibit himself as - John

Conington, Professor of Latin

Meantime, I had discovered the depth of my iniquity, and fled

to the rooms of Duckworth, a scholar, to whom I recounted my

adventure, and with whom I stayed. Late in the evening a note was

brought in for Duckworth, who said, "It is a note from John

Conington," and read - "Dear Duckworth, having been the

victim of a cruel outrage on the part of some undergraduates of

the college, I trust to your friendship for me to assist me in

finding out the perpetrators," &c. Duckworth urged that

I should give myself up - that John Conington was very

good-natured - in fact, that I had better confess the whole

truth, &c. So I immediately sat down and wrote the whole

story to Professor Conington, and not till I had sent it, and it

was safe in his hands, did Duckworth confess that the note he had

received was a forgery, that he had contrived to slip out of the

room and write it to himself-and that I had made my confession

unnecessarily. However, he went off with the story and its latest

additions to the Professor, and no more was said.

If Milligan was my constant companion in college, George

Sheffield and I were inseparable out of doors, though I often

wondered at his caring so much to be with me, as he was a capital

rider, shot, oarsman - in fact, everything which I was not. I

believe we exactly at this time, and for some years after,

supplied each other's vacancies. It was the most wholesome, best

kind of devotion, and, if we needed any ennobling influence, we

always had it at hand in Mrs. Eliot Warburton, who sympathised in

all we did, and who, except his mother, was the only woman whom I

ever knew George Sheffield have any regard for. It was about this

time that the Bill was before Parliament for destroying the

privileges of Founder's kin. While it was in progress, we

discovered that George was distinctly "Founder's kin"

to Thomas Teesdale, the founder of Pembroke, and half because our

ideas were conservative, half because we delighted in an

adventure of any kind, we determined to take advantage of the

privilege. Dr. Jeune, afterwards Bishop of Peterborough, was

Master of Pembroke then, and was perfectly furious at our

audacity, which was generally laughed at at the time, and treated

as the mere whim of two foolish schoolboys; but we would not be

daunted, and went on our own way. Day after day I studied with

George the subjects of his examination, goading him on. Day after

day I walked down with him to the place of examination, doing my

best to screw up his courage to meet the inquisitors. We went

against the Heads of Houses with the enthusiasm of martyrs in a

much greater cause, and we were victorious. George Sheffield was

forcibly elected to a Founder's-kin Scholarship at Pembroke, and

was the last so elected. Dr. Jeune was grievously annoyed, but,

with the generosity which was always characteristic of him, he at

once accorded us his friendship, and remained my most warm and

honoured friend till his death about ten years afterwards. He was

remarkable at Oxford for dogmatically repealing the law which

obliged undergraduates to receive the Sacrament on certain days

in the year. "In future," he announced in chapel,

"no member of this college will be compelled to eat and

drink his own damnation."

In urging George Sheffield to become a scholar of Pembroke, I

was certainly disinterested ; without him University lost half

its charms, and Oxford was never the same to me without

"Giorgione" - the George of Georges. But our last

summer together was uncloudedly happy. We used to engage a little

pony-carriage at the Maidenhead, with a pony called Tommy, which

was certainly the most wonderful beast for bearing fatigue, and

as soon as ever the college gates were opened, we were "over

the hills and far away." Sometimes we would arrive in time

for breakfast at Thame, a quaint old town quite on the

Oxfordshire boundary, where John Hampden was at school. Then we

would mount the Chiltern Hills with our pony, and when we reached

the top, look down upon the great Buckinghamshire plains, with

their rich woods; and when we saw the different gentlemen's

places scattered about in the distance, we used to say,

"There we will go to luncheon" - "There we will go

to dinner," and the little programmes we made we always

carried out; for having each a good many relations and friends,

we seldom found we had no link with any of the places we came to.

Sometimes Albert Rutson would ride by the side of our carriage,

but I do not think that either then or afterwards we quite liked

having anybody with us, we were so perfectly contented with each

other, and had always so much to say to each other. Our most

delightful day of all was that on which we had luncheon at Great

Hampden with Mr. and Lady Vere Cameron and their daughters, who

were slightly known to my mother; and dined at the wonderful old

house of Chequers, filled with relics of the Cromwells, the

owner, Lady Frankland Russell, being a cousin of Lady

Sheffield's. Most enchanting was the late return from these long

excursions through the lanes hung with honeysuckle and clematis,

satiated as we were, but not wearied with happiness, and full of

interest and enthusiasm in each other and in our mutual lives,

both past and present. One of the results of our frequent visits

to the scenes of John Hampden's life was a lecture which I was

induced to deliver in the town-hall at Oxford, during the last

year of my Oxford life, upon John Hampden - a lecture which was

sadly too short, because at that time I had no experience to

guide me as to how long such things would take.

It was during this spring that my mother was greatly

distressed by the long-deferred declaration of Mary Stanley that

she had become a Roman Catholic.1 A burst of family indignation

followed, during which I constituted myself Mary's defender,

utterly refused to make any difference with her, as well as

preventing my mother from doing so ; and many were the battles I

fought for her.

A little episode in my life at this time

was the publication of my first book - a very small one,

"Epitaphs for Country Churchyards." It was published by

John Henry Parker, who was exceedingly good-natured in

undertaking it, for it is needless to say it was not remunerative

to either of us. The ever-kind Landor praised the preface very

much, and delighted my mother by his grandiloquent announcement

that it was "quite worthy of Addison!"

At this time also my distant cousin Henry

Liddell was appointed to the Deanery of Christ Church. He had

previously been Headmaster of Westminster, and during his

residence there had become celebrated by his Lexicon. One day he

told the boys in his class that they must write an English

epigram. Some of them said it was impossible. He said it was not

impossible at all; they might each choose their own subject, but

an epigram they must write. One boy wrote –

"Two men wrote a

Lexicon,

Liddell and Scott ;

One half was clever,

And one half was not.

Give me the answer, boys,

Quick to this riddle,

Which was by Scott

And which was by Liddell?"

Dr. Liddell, when it was shown up, only

said, "I think you are rather severe."

As to education, I did not receive much

more at Oxford this year than I had done before. The college

lectures were the merest rubbish; and of what was learnt to pass

the University examinations, nothing has since been of use to me,

except the History for the final Schools. About fourteen years of

life and above £4000 I consider to have been wasted on my

education of nothingness. At Oxford, however, I was not idle, and

the History, French, and Italian, which I taught myself, have

always been useful.

To My MOTHER.

"Oxford, Feb. 19, 1856. -

Your news about dear Mary (Stanley) is very sad. She will find

out too late the mistake she has made: that, because she cannot

agree with everything in the Church of England, she should think

it necessary to join another, where, if she receives anything,

she will be obliged to receive everything. I am sorry that the

person chosen to argue with her was not pne whose views were more

consistent with her own than Dr. Vaughan's. It is seldom

acknowledged, but I believe that, by their tolerance, Mr. Liddell

and Mr. Bennett2 keep as many people from Rome as

other people drive there. I am very sorry for Aunt Kitty, and

hope that no one who loves her will add to her sorrow by

estranging themselves from Mary - above all, that you will not

consider her religion a barrier. When people see how nobly all

her life is given to good, and how she has even made this great

step, at sacrifice to herself because she believes that good may

better be carried out in another Church, they may pity her

delusion, but no person of right feeling can possibly be angry

with her. And, after all, she has not changed her religion. It

is, as your own beloved John Wesley said, on hearing that his

nephew had become a Papist – 'He has changed his opinions

and mode of worship, but has not changed his religion: that is

quite another thing.'"

JOURNAL.

"Lime, March 30, 1856. - My

mother and I have had a very happy Easter together - more than

blessed when I look back at the anxiety of last Easter. Once when

her bell rang in the night, I started up and rushed out into the

passage in an agony of alarm, for every unusual sound at home has

terrified me since her illness; but it was nothing. I have been

full of my work, chiefly Aristotle's Politics, for 'Greats' - too

full, I fear, to enter as I ought into all her little thoughts

and plans as usual: but she is ever loving and gentle, and had

interest and sympathy even when I was preoccupied. She thinks

that knowledge may teach humility even in a spiritual sense. She

says, 'In knowledge the feeling is the same which one has in

ascending mountains - that, the higher one gets, the farther one

is from heaven.' To-day, as we were walking amongst the flowers,

she said, 'I suppose every one's impressions of heaven are

according to the feeling they have for earthly things: I always

feel that a garden is my impression - the garden of Paradise.'

'People generally love themselves first, their friends next, and

God last,' she said one day. 'Well, I do not think that is the

case with me,' I replied; 'I really believe I do put you first

and self next.' 'Yes, I really think you do,' she said."

When I returned to Oxford after Easter,

1856, my pleasant time in college rooms was over, and I moved to

lodgings over Wheeler's bookshop and facing Dr. Cradock's house,

so that I was able to see more than ever of Mrs. Eliot Warburton.

I was Jmost immediately in the "Schools," for the

classical and divinity part of my final examination, which I got

through very comfortably. While in the Schools at this time, I

remember a man being asked what John the Baptist was beheaded for

- and the answer, "Dancing with Herodias's daughter!"

Once through these Schools, I was free for some time, and

charades were our chief amusement, Mrs. Warburton, the Misses

Elliot,3 Sheffield, and I being the

principal actors. The proclamation of peace after the Crimean War

was celebrated - Oxford fashion - by tremendous riots in the

town, and smashing of windows in all directions.

At Whitsuntide, I had a little tour in

Warwickshire with Albert Rutson as my companion. We enjoyed a

stay at Edgehill, at the charming little inn called "The Sun

Rising," which overlooks the battlefield, having the great

sycamore by its side under which Charles I. breakfasted before

the battle, and a number of Cavalier arms inside, with the

hangings of the bed in which Lord Lindsey died. From Edgehill I

saw the wonderful old house of the Comptons at Compton-Whinyates,

with its endless secret staircases and trap-doors, and its rooms

of unplaned oak, evidently arranged with no other purpose than

defence or escape. We went on to Stratford-on-Avon, with

Shakspeare's tomb, his house in Henley Street, and the pretty old

thatched cottage where he wooed his wife - Anne Hathaway. Also we

went to visit Mrs. Lucy (sister of Mrs. William Stanley) at

Charlecote, a most entertaining person, with the family

characteristic of fun and good-humour; and to Combe Abbey, full

of relics of Elizabeth of Bohemia and her daughters, who lived

there with Lord Craven. Many of the portraits were painted by her

daughter Louisa. A few weeks later I went up to the Stanleys in

London for the Peace illuminations - "very neat, but all

alike," as I heard a voice in the crowd say. I saw them from

the house of Lady Mildred Hope, who had a party for them like the

one in Scripture, not the rich and great, but the "poor,

maimed, halt, and blind;" as, except Aldersons and Stanleys,

she arranged that there should not be a single person "in

society" there.

JOURNAL.

"Lime, June 8, 1856. - I had

found the dear mother in a sadly fragile state, so infirm and

tottering that it is not safe to leave her alone for a minute,

and she is so well aware of it, that she does not wish to be

left. She cannot now even cross the room alone, and never thinks

of moving anywhere without a stick. Every breath, even of the

summer wind, she feels most intensely. '"The Lord establish,

strengthen you," that must be my verse,' she says."

"June 15. - I am afraid I

cannot help being tired of the mental solitude at home, as the

dear mother, without being ill enough to create any anxiety, has

not been well enough to take any interest, or have any share in

my doings. Sometimes I am almost sick with the silence, and, as I

can never go far enough from her to allow of my leaving the

garden, I know not only every cabbage, but every leaf upon every

cabbage."

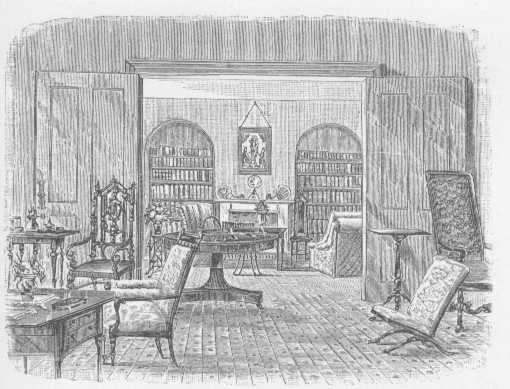

DRAWING-ROOM, LIME.

"June 29. - We have been for

a week with the Stanleys at Canterbury, and it was very pleasant

to be with Arthur, who was his most charming self."

Early in July, I preceded my mother

northwards, made a little sketching tour in Lincolnshire, where

arriving with little luggage, and drawing hard all day, I excited

great commiseration amongst the people as a poor travelling

artist. "Eh, I shouldn't like to have such hard work as that

on. Measter, I zay, I should'na like to be you."

At Lincoln I joined my mother, and we

went on together to Yorkshire, where my friend Rutson lent us a

charming old manor-house, Nunnington Hall near Helmsley, the

centre of an interesting country, in which we visited the

principal ruined abbeys of Yorkshire. My mother entirely

recovered here, and was full of enjoyment. On our way to

Harrogate, a Quakeress with whom we travelled persecuted me with

"The Enquiring Parishioner on the Way to Salvation,"

and then, after looking at my sketches, hoped that "one so

gifted was not being led away by Dr. Pusey!" At Bolton we

stayed several days at the Farfield Farm, and thence drove

through Swale Dale to Richmond. On our way farther north, I paid

my first visit to my cousins at Ravensworth, and very alarming I

thought it; rejoining my mother at Warkworth, a place I have

always delighted in, and where Mrs. Clutterbuck4

and her daughters were very kind to us. More charming still were

the next few days spent with my kind old cousin Henry Liddell

(brother-in-law of my Aunt Ravensworth) in Bamborough Castle.

We visited Dryburgh and Jedburgh, and the

vulgar commonplace villa, with small ill-proportioned rooms

looking out upon nothing at all, out of which Sir Walter Scott

created the Abbotsford of his imagination. Charlotte Leycester

having joined us, I left my mother at the Bridge of Allan for a

little tour, in the first hour of which I, Italian-fashion, made

a friendship with one with whom till her death I continued to be

most intimate:

To MY MOTHER.

"Tillycouttry House, August

12, 1856. - My mother will be surprised that, instead of writing

from an inn, I should date from one of the most beautiful places

in the Ochils, and that I should be staying with people whom,

though we met for the first time a few hours ago, I already seem

to know intimately.

"When I left my mother and entered

the train at Stirling, two ladies got in after me; one old,

yellow, and withered; the other, though elderly, still handsome,

and with a very sweet interesting expression. She immediately

began to talk. 'Was I a sportsman?' - 'No, only a tourist.' -

'Then did I know that on the old bridge we were passing, the

Bishop of Glasgow long ago was hung in full canonicals?' And with

such histories the younger of the two sisters, in a very sweet

Scottish accent, animated the whole way to Alloa. Having arrived

there, she said, 'If we part now, we shall probably never meet

again: there is no time for discussion, but be assured that my

husband, Mr. Dalzell, will be glad to see you. Change your ticket

at once, and come home with me to Tillycoultry.' And . . . I

obeyed; and here I am in a great, old, half-desolate house, by

the side of a torrent and a ruined churchyard, under a rocky part

of the Ochils.

"Mr. Dalzell met us in the avenue.

He is a rigid maintainer of the Free Kirk, upon which Mrs. Huggan

(the old sister) says he spends all his money - about £ 18,ooo a

year - and he is very odd, and passes three-fourths of the day

quite alone, in meditation and prayer. He has much sweetness of

manner in speaking, but seems quite hazy about things of earth,

and entirely rapt in prophecies and thoughts either of the second

coming of Christ or of the trials of the Kirk part of his Church

on earth.

"Mrs. Dalzell is quite different,

truly, beautifully, practically holy. She 'feels,' as I heard her

say to her sister to-night, 'all things are wrapt up in Christ.'

The evening was very long, as we dined at four, but was varied by

music and Scotch songs.

"The old Catholic priest who once

lived here cursed the place, in consequence of which it is

believed that there are - no little birds!"

"Dunfermilne, August 13. -

This morning I walked with Mr. Dalzell to Castle Campbell - an

old ruined tower, on a precipitous rock in a lovely situation

surrounded by mountains, the lower parts of which are clothed

with birch woods. Inside the castle is a ruined court, where John

Knox administered his first Sacrament. On the way we passed the

little burial-ground of the Taits, surrounded by a high wall,

only open on one side, towards the river Devon."

"Falkland, August 14. -After

drawing in beautiful ruined Dunfermline, I drove to Kinross, and

embarked in the 'Abbot' for the castle of Loch Leven, which rises

on its dark island against a most delicate distance of low

mountains. . . . There is a charming old-fashioned inn here, and

a beautiful old castle, in one of the rooms of which the young

Duke of Rothesay was starved to death by his uncle."

"St Andrews, August 15. -

This is a glorious place, a rocky promontory washed by the sea on

both sides, crowned by Cardinal Beaton's castle, and backed by a

perfect crowd of ecclesiastical ruins. The cathedral was the

finest in Scotland, but destroyed in one day by a mob instigated

by John Knox, who ought to have been flayed for it. Close by its

ruins is a grand old tower, built by St. Regulus, who 'came with

two ships' from Patras, and died in one of the natural caves in

the cliff under the castle. In the castle itself is Cardinal

Beaton's dungeon, where a Lord Airlie was imprisoned, and whence

he was rescued by his sister, who dressed him up in her

clothes."

"Brechin, August 17. - The

ruin of Arbroath (Aberbrothock) is most interesting. William the

Lion is buried before the high altar, and in the chapter-house is

the lid of his coffin in Scottish marble, with his headless

figure, the only existing effigy of a Scottish king. In the

chapter-house a man puts into your hand what looks like a lump of

decayed ebony, and you are told it is the 'blood, gums, and

intestines' of the king. You also see the skull of the Queen, the

thigh-bone of her brother, and other such relics of royalty. Most

beautiful are the cliffs of Arbroath, a scene of Scott's

'Antiquary.' From a natural terrace you look down into deep tiny

gulfs of blue water in the rich red sandstone rock, with every

variety of tiny islet, dark cave, and perpendicular pillar; and,

far in the distance, is the Inchcape Rock, where the Danish

pirate stole the warning bell and was afterwards lost himself;

which gave rise to the ballad of 'Sir Patrick Spens.' The Pictish

tower here is most curious, but its character injured by the

cathedral being built too near."

I have an ever-vivid recollection of a

most piteous Sunday spent in the wretched town of Brechin, with

nothing whatever to do, as in those days it would have made my

mother too miserable if I had travelled at all on a Sunday - the

wretched folly of Sabbatarianism (against which our Saviour so

especially preached when on earth) being then rife in our family,

to such a degree, that I regard with loathing the recollection of

every seventh day of my life until I was about eight-and-twenty.5 After leaving Brechin, I saw the noble castle of Dunottar,

and joined my mother at Braemar, where we stayed at the inn, and

Charlotte Leycester at a tiny lodging in a cottage thatched with

peat. I disliked Braemar extremely, and never could see the

beauty of that much-admired valley, with its featureless hills,

half-dry river, and the ugly castellated house of Balmoral. Dean

Alford and his family were at Braemar, and their being run away

with in a carriage, our coming up to them, our servant John

stopping their horses, the wife and daughters being taken into

our carriage, and my walking back with the Dean, first led to my

becoming intimate with him. I remember, during this walk, the

description he gave me of the "Apostles' Club" at

Cambridge, of which Henry Hallam was the nucleus and centre, and

of which Tennyson was a member, but from which he was turned out

because he was too lazy to write the necessary essay. Hallam, who

died at twenty-two, had "grasped the whole of literature

before he was nineteen." The Alfords were travelling without

any luggage, and could consequently walk their journeys anywhere

- that is, each lady had only a very small hand-bag, and the Dean

had a walking-stick, which unscrewed and displayed the materials

of a dressing-case, a pocket inkstand, and a candlestick.On our

way southwards I first saw Glamis. I did not care about the

places on the inland Scottish lakes, except Killin, where our

cousin Fanny Tatton and her friend Miss Heygarth joined us, and

where we spent some pleasant week-days and a most abominable

Sunday. We afterwards lingered at Arrochar on Loch Long, whither

Aunt Kitty and Arthur Stanley came to us from Inverary. We

returned to Glasgow by the Gareloch, which allowed me to visit at

Paisley the tomb of my royal ancestress, Marjory Bruce. At

Glasgow, though we were most uncomfortable in a noisy and very

expensive hotel, my mother insisted upon spending a wretched day,

because of - Sunday! We afterwards paid pleasant

visits at Foxhow and Toft, whence I went on alone to Peatswood in

Shropshire (Mr. Twemlow's), and paid from thence a most affecting

visit to our old home at Stoke, and to Goldstone Farm, the home

of my dear Nurse Lea. Hence I returned with Archdeacon and Mrs.

Moore to Lichfield, and being there when the grave of St. Chad

was opened, was presented with a fragment of his body

- a treasure inestimable to Roman Catholics, which I possess

still.

During the remaining weeks of autumn,

before I returned to Oxford, we had many visitors at Lime,

including my new friend Mrs. Dalzell, whose goodness and

simplicity perfectly charmed my mother.

We passed the latter part of the winter

between the Penrhyns' house at Sheen, Aunt Kitty's house of 6

Grosvenor Crescent, and Arthur Stanley's Canonry at Canterbury.

With Arthur I dined at the house of Mr. Woodhall, a Canterbury

clergyman, now a Roman Catholic priest, having been specially

invited to meet (at a huge horseshoe table) "the middle

classes" - a very large party of chemists, nurserymen,

&c., .and their wives, and very pleasant people they were. I

used to think Canterbury perfectly enchanting, and Arthur was

most kind and charming to me. While there, I remember his

examining a school at St. Stephen's, and asking the meaning of

bearing false witness against one's neighbour - "When nobody

does nothing to nobody," answered a child, "and

somebody goes and tells."

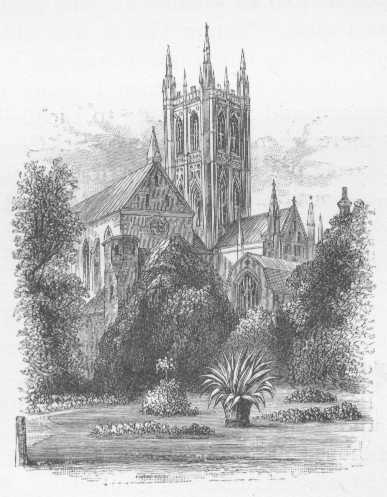

FROM THE DEAN'S GARDEN, CANTERBURY.

In returning to Oxford in 1857, I

terribly missed my constant companions hitherto - Milligan and

Sheffield, who had both left, and, except perhaps Forsyth Grant,

I had no real friends left, though many pleasant acquaintances,

amongst whom I had an especial regard for Tom Brassey, the

simple, honest, hard working son of the great contractor and

millionaire - afterwards my near neighbour in Sussex, whom I have

watched grow rapidly up from nothing to a peerage, with only

boundless money and common-sense as his aides-de-camp. The men I

now saw most of were those who called themselves the dwdeka - generally reputed "the fast

men" of the college. but a manly high-minded set of feflows.

Most of my time was spent in learning Italian with Count Saffi,

who, a member of the well-known Roman triumvirate, was at that

time residing at Oxford with his wife, née Nina Crauford

of Portincross.6 I was great friends with this

remarkable man, of a much-tried and ever-patient countenance, and

afterwards went to visit him at Forli. I may mention Godfrey

Lushington (then of All Souls) as an acquaintance of whom I saw

much at this time, and whom I have always liked and respected

exceedingly, though our paths in life have not brought us often

together since. It was very difficult to distinguish him from his

twin-brother Vernon; indeed, it would have been impossible to

know them apart, if Vernon had not, fortunately for their

friends, shot off some of his fingers.In March (1857) I was proud

to receive my aunt, Mrs. Stanley, with all her children, Mrs.

Grote, and several others, at a luncheon in my rooms in honour of

Arthur Stanley's inaugural lecture as Professor of

Ecclesiastical History, in which capacity his lectures, as indeed

all else concerning him, were subjects of the greatest interest

to me, my affection for him being that of a devoted younger

brother.I was enchanted with Mrs. Grote, whom De Tocqueville

pronounced

"the cleverest woman of his

acquaintance," though her exterior - with a short waist,

brown mantle of stamped velvet, and huge bonnet, full of

full-blown red roses - was certainly not captivating. Sydney

Smith always called her "Grota," and said she was the

origin of the word grotesque. Mrs. Grote was celebrated for

having never felt shy. She had a passion for discordant colours,

and had her petticoats always arranged to display her feet and

ankles, of which she was excessively proud. At her own home of

Burnham she would drive out with a man's hat and a coachman's

cloak of many capes. She had an invalid friend in that

neighbourhood, who had been very seriously ill, and was still

intensely weak. When Mrs. Grote proposed coming to take her for a

drive, she was pleased, but was horrified when she saw Mrs. Grote

arrive in a very high dogcart, herself driving it. With great

pain and labour she climbed up beside Mrs. Grote, and they set

off For some time she was too exhausted to speak, then she said

something almost in a whisper. "Good God! don't speak so

loud," said Mrs. Grote, "or you'll frighten the horse:

if he runs away, God only knows when he'll stop."

On the . occasion of this visit at

Oxford, Mrs. Grote sat with one leg over the other, both high in

the air, and talked for two hours, turning with equal facility to

Saffi on Italian Literature, Max Müller on Epic Poetry, and

Arthur on Ecclesiastical History, and then plunged into a

discourse on the best manure for turnips and the best way of

forcing Cotswold mutton, with an interlude first upon the

"harmony of shadow" in watercolour drawing, and then

upon rat-hunts at Jemmy Shawe's - a low public-house in

Westminster. Upon all these subjects she was equally vigorous,

and gave all her decisions with the manner and tone of one laying

down the laws of Athens. She admired Arthur excessively, but was

a capital friend for him, because she was not afraid of laughing

- as all his own family were - at his morbid passion for

impossible analogies. In his second lecture Arthur made a capital

allusion to Mn Grote, while his eyes were fixed upon the spouse

of the historian, and when she heard it, she thumped with both

fists upon her knees, and exclaimed loudly, "Good God! how

good!" I did not often meet Mrs. Grote in after life, but

when I did, was always on very cordial terms with her. She was,

to the last, one of the most original women in England, shrewd,

generous, and excessively vain. I remember hearing that when she

published her Life of her husband, Mr. Murray was obliged to

insist upon her suppressing one sentence, indescribably comic to

those who were familiar with her uncouth aspect. It was -

"When George Grote and I were young, we were equally

distinguished by the beauty of our persons and the vivacity of

our conversation!" Her own true vocation she always declared

was that of an opera-dancer.Arthur Stanley made his home with me

during this visit to Oxford, but one day I dined with him at

Oriel, where we had "Herodotus pudding" - a dish

peculiar to that college.

JOURNAL.

"Lime, Easter Sunday, April

12, 1857. - I have been spending a happy fortnight at home. The

burst of spring has been beautiful - such a golden carpet of

primroses on the bank, interspersed with tufts of still more

golden daffodils, hazels putting forth their fresh green, and

birds singing. My sweet mother is more than usually patient under

the trial of failure of sight - glad to be read to for hours, but

contented to be left alone, only saying sometimes - 'Now,

darling, come and talk to me a little.' On going to church this

morning, we found that poor Margaret Coleman, the carpenter's

wife, had, as always on this day, covered Uncle Julius's grave

with flowers. He is wonderfully missed by the people, though they

seldom saw him except in church; for, as Mrs. Jasper Harmer said

to me the other day, 'We didn't often see him, but then we knew

he was always studying us - now wasn't he?'"

A subject of intense interest after my

return to . Oxford was hearing Thackeray deliver his lectures on

the Georges. That which spoke of the blindness of George III.,

with his glorious intonation, was indescribably pathetic. It was

a great delight to have George Sheffield back and to resume our

excursions, one of which was to see the May Cross of

Charlton-on-Ottmoor, on which I published a very feeble story in

a magazine; and another to Abingdon, where we had luncheon with

the Head-master of the Grammar School, who, as soon as it was

over, apologised for leaving us because he had got "to

wallop so many boys." All our visits to Abingdon ended in

visits to the extraordinary old brothers Smith, cobblers, who

always sat cross-legged on a counter, and always lived upon raw

meat. We had heard of their possession of an extraordinary old

house which no one had entered, and we used to try to persuade

them to take us there; but when we asked one he said, "I

would, but my brother Tom is so eccentric, it would be as much as

my life is worth - I really couldn't;" and when we asked the

other he said, "I would, but you've no idea what an

extraordinary man my brother John is; he would never

consent." However, one day we captured both the old men

together and over-persuaded them (no one ever could resist

George), and we went to the old house, a dismal tumble-down

building, with shuttered windows, outside the town. Inside it was

a place of past ages - old chairs and cupboards of the sixteenth

century, old tapestries, and old china, but all deep, deep in

dust and dirt, which was never cleaned away. It was like the

palace of the Sleeping Beauty after the hundred years' sleep. I

have several pieces of china out of that old house now -

"Gris de Flandres ware."

In June I made a little tour, partly of

visits, and from Mrs. Vaughan's house at Leicester had an

enchanting expedition to Bradgate, the ruined home of Lady Jane

Grey, in a glen full of oaks and beeches of immense age.

In my final (History and Law) Schools I

had passed with great ease, and had for some time been residing

at Oxford as a Bachelor, having taken my degree. But as one

friend after another departed, the interest of Oxford had faded.

I left it on the 13th of June 1857, and without regret.