III

BOYHOOD

1843-1848

"The more we live, more brief appear Our

life's returning stages:

A day to childhood seems an year, And years like passing ages."

- THOMAS CAMPBELL.

"Oh if in time of sacred youth,

We learned at home to love and pray,

Pray Heaven that early Love and Truth

May never wholly pass away."

-THACKERAY.

MY mother took me to Harnish Rectory on July 28, 1843. The

aspect of Mr. Kilvert, his tall figure, and red hair encircling a

high bald forehead, was not reassuring, nor were any temptations

offered by my companions (who were almost entirely of a rich

middle class), or by the playground, which was a little gravelled

courtyard - the stable-yard, in fact - at the back of the house.

The Rectory itself was a small house, pleasantly situated on a

hill, near an odd little Wrenian church which stood in a well-kept

churchyard. We were met at Harnish by Mrs. Pile, who, as daughter

of an Alton farmer, was connected with the happiest period of my

mother's life, and while I was a prey to the utmost anguish,

talking to her prevented my mother from thinking much about

parting with me.

One miserable morning Mr. Kilvert, Mrs. Pile, and I went with

my mother and Lea to the station at Chippenham. Terrible indeed

was the moment when the train came up and I flung myself first

into Lea's arms and then into my mother's. Mrs. Pile did her best

to comfort me - but . . . there was no comfort.

Several boys slept in a room together at Harnish. In mine

there was at first only one other, who was one of the greatest

boy-blackguards I ever came across-wicked, malicious, and

hypocritical. He made my life indescribably miserable. One day,

however, whilst we were wearily plodding through our morning

lessons, I saw a pleasant gentleman - like boy come through the

gate, who was introduced to us as Alick MacSween. He was thirteen,

so much older than any of the others, and he was very good-looking,

at least we thought so then, and we used to apply to him the line

in our Syntax -

"Ingenui vultus puer ingenuique pudoris."

It was a great joy to find myself transferred to his room, and

he soon became a hero in my eyes. Imagination endowed him with

every grace, and I am sure, on looking back, that he really was a

very nice boy. Gradually I had the delight of feeling assured

that Alick liked me as much as I liked him. We became everything

to each other, and shared our lockers in school, and our little

gardens in play-hours. Our affection made sunshine in the

dreariness:

My one dread was that Alick would some day like another boy

better than he liked me. It happened. Then, at ten years old,

life was a blank. Soon afterwards Alick left the school, and a

little later, before he was fifteen, I heard that he was dead. It

was a dumb sorrow, which I could speak to no one, for no one

would have understood it, not even my mother. It is all in the

dim distance of the long ago. I could not realise what Alick

would be if he was alive, but my mind's eye sees him now as he

was then, as if it were yesterday: I mourn him still.

Mr. Kilvert, as I have said, was deeply "religious,"

but he was very hot-tempered, and slashed our hands with a ruler

and our bodies with a cane most unmercifully for exceedingly

slight offences. So intense, so abject was our terror of him,

that we used to look forward as to an oasis to the one afternoon

when he went td his parish duties, and Mrs. Kilvert or her sister

Miss Sarah Coleman attended to the school, for, as the eldest boy

was not thirteen, we were well within their capacities. The

greater part of each day was spent in lessons, and oh! what trash

we were wearisomely taught; but from twelve to one we were taken

out for a walk, when we employed the time in collecting all kinds

of rubbish-bits of old tobacco-pipe, &c. - to make "museums."

To My MOTHER.

"DARLING MAMA, - I like it rather

better than I expected. They have killed a large snake by

stoning it, and Gumbleton has skinned it, such nasty work,

and peged it on a board covered with butter and pepper, and

layed it out in the sun to dry. It is going to be stuffed. Do

you know I have been in the vault under the church. It is so

dark. There are great big coffins there. The boy's chief game

is robbers. Give love and 8 thousand kisses to Lea and love

to the Grannies. Good-bye darling Mama."

"Frederick Lewis has been very ill of

crop. Do you know what that is? I have been to the school-feast

at Mr. Clutterbuck's. It was so beautifull. All the girls

were seated round little round tables amongst beds of

geraniums, heliotrope, verbenas, and balm of Gilead We

carried the tea and were called in to grapes and gooseberries,

and we played at thread-the-needle and went in a swing and in

a flying boat. Good-bye Mamma."

"MY DEAR MAMMA,-The boys have got two

dear little rabbits. They had two wood-pigeons, but they died

a shocking death, being eaten of worms, and there was a large

vault made in which was interred their bodies, and that of a

dear little mouse who died too. All went into mourning for it."

"MY DEAR MAMMA,-We have been a

picknick at a beautiful place called Castlecomb. When we got

there we went to see the dungeon. Then we saw a high tower

half covered with ivy. You must know that Castlecomb is on

the top of an emense hilt so that you have to climb hands and

knees. When we sate down to tea, our things rolled down the

hill. We rambled about and gathered nuts, for the trees were

loaded. In the town there is a most beautiful old carved

cross and a church. Good-bye darling Mamma."

"Nov.1. - I will tell you a day

at Mr. Kilvert's. I get up at half-past six and do lessons

for the morning. Then at eight breakfast. Then go out till

half-past nine. Then lessons till eleven. Then go out till a

quarter-past eleven. Then lessons till 12, go a walk

till 2 dinner. Lessons from half-past three, writing, sums,

or dictation. From 5 till 6 play. Tea. Lessons from 7 to 8.

Bed. I have collected two thousand stamps since I was here.

Do you ever take your pudding to the poor women on Fridays

now? Goodbye darling Mamma."

As the holidays approached, I became ill with excitement and

joy, but all through the half years at Harnish I always kept a

sort of map on which every day was represented as a square to be

filled up when lived through. Oh, the dreary sight of these

spaces on the first days: the ecstasy when only one or two

squares remained white!

From, MY MOTHER'S JOURNAL.

"When I arrived at Harnish, Augustus

was looking sadly ill. As the Rectory door was opened, the

dear boy stood there, and when he saw us, he could not speak,

but the tears flowed down his cheeks. After a while he began

to show his joy at seeing us.

The Marcus Hares were at Hurstmonceaux all the winter, and a

terrible trial it was to me, as my Aunt Lucy was more jealous

than ever of any kind word being spoken to me. But I had some

little pleasures when I was at Hurstmonceaux Place with the large

merry family of the Bunsens, who had a beautiful Christmas-tree.

There is nothing to tell of my school-life during the next

year, though my mind dwells drearily on the long days of

uninstructive lessons in the close hot schoolroom when so

hopelessly "nous suyons à grosses gouttes," as Mme. de

Sévigné says; or on the monotonous confinement in

the narrow court which was our usual playground; and my

recollection shrinks from the reign of terror under which we

lived. In the summer I was delivered from Hurstmonceaux, going

first with my mother to our dear Stoke home, which I had never

seen before in all its wealth of summer flowers, and proceeding

thence to the English lakes, where the delight of the flowers and

the sketching was intense. But our pleasure was not unalloyed,

for, though Uncle Julius accompanied us, my mother took Esther

Maurice with her, wishing to give her a holiday after her hard

work in school-teaching at Reading, and never foreseeing, what

every one else foresaw, that Uncle Julius, who had always a

passion for governesses, would certainly propose to her. Bitter

were the tears which my mother shed when this result - to her

alone unexpected - actually took place. It was the most dismal of

betrothals: Esther sobbed and cried, my mother sobbed and cried,

Uncle Julius sobbed and cried daily. I used to see them sitting

holding each other's hands and crying on the banks of the Rotha.

These scenes for the most part took place Foxhow, where we.

paid a long visit to Mrs. Arnold, whose children were delightful

companions to me. Afterwards we rented a small damp house near

Ambleside - Rotha Cottage - for some weeks, but I was very ill

from its unhealthiness, and terribly ill afterwards at Patterdale

from the damp of the place. Matthew Arnold, then a very handsome

young man, was always excessively kind to me, and I often had

great fun with him and his brothers: but he was not considered

then to give any proof the intellectual powers he showed

afterwards. From Foxhow and Rotha Cottage we constantly visited

Wordsworth and his dear old wife at Rydal Mount, and we walked

with him to the Rydal Falls. He always talked a good deal about

himself and his own poems, and I have a sense of his being not

vain, but conceited. I have been told since, in confirmation of

this, that when Milton's watch - preserved somewhere - was shown

to him, he instantly and involuntarily drew out his own watch,

and compared, not the watches, but the poets. The "severe

creator of immortal things," as Landor called him, read us

some of his verses admirably,1 but I was too young at this time to be

interested in much of his conversation, unless it was about the

wild-flowers, to which he was devoted, as I was. I think that at

Keswick we also saw Southey, but I do not remember him, though I

remember his (very ugly) house very well. In returning south we

saw Chester, and paid a visit to an old cousin of my mother's -

" Dosey (Theodosia) Leigh," who had many quaint sayings.

In allusion to her own maiden state, she would often complacently

quote the old Cheshire proverb "Bout's bare but it's yezzy."2

While at Chester, though I forget how, I

first became conscious how difficult the having Esther Maurice

for an aunt would make everything in life to me. I was, however,

at her wedding in November at Reading.

The winter of 1844-45 was the first of

many which were made unutterably wretched by "Aunt Esther."

Aunt Lucy had chastised me with rods, Aunt Esther did indeed

chastise me with scorpions. Aunt Lucy was a very refined person,

and a very charming and delightful companion to those she loved,

and, had she loved me, I should have been devoted to her. Aunt

Esther was, from her own personal characteristics, a person I

never could have loved. Yet my uncle was now entirely ruled by

her, and my gentle mother considered her interference in

everything as a cross which was "sent to her" to be

meekly endured. The society at the Rectory was now entirely

changed: all the relations of the Hare family, except the Marcus

Hares, were given to understand that their visits were unwelcome,

and the house was entirely filled with the relations of Aunt

Esther old Mr. and Mrs. Maurice; their married daughter Lucilla

Powell, with her husband and children; their unmarried daughters

- Mary, Priscilla, and Harriet.3 - Priscilla, who now never left her bed, and

who was violently sick after everything she ate (yet with the

most enormous appetite), often for many months together.

With the inmates of the

house, the whole "tone" of the Rectory society was

changed. It was impossible entirely to silence Uncle Julius, yet

at times even he was subdued by his new surroundings, the circle

around him being incessantly occupied with the trivialities of

domestic or parochial detail, varied by the gossip of such a

tenth-rate provincial town as Reading, or reminiscences of the

boarding-school which had been their occupation and pride for so

many years. Frequently also the spare rooms were filled by former

pupils – "young ladies" of a kind who would

announce their engagement by "The infinite grace of God has

put it into the heart of his servant Edmund to propose to me,"

or "I have been led by the mysterious workings of God's

providence to accept the hand of Edgar,"4 - expressions which

Aunt Esther, who wrote good and simple English herself, would

describe as touching evidences of a Christian spirit in her

younger friends.

But what was far more

trying to me was, that in order to prove that her marriage had

made no difference in the sisterly and brotherly relations which

existed between my mother and Uncle Julius, Aunt Esther insisted

that my mother should dine at the Rectory every night, and

as, in winter, the late return in an open carriage was impossible,

this involved our sleeping at the Rectory and returning home

every morning in the bitter cold before breakfast. The hours

after five o'clock in every day of the much-longed-for, eagerly

counted holidays, were now absolute purgatory. Once landed at the

Rectory, I was generally left in a dark room till dinner at seven

o'clock, for candles were never allowed in winter in the room

where I was left alone. After dinner I was never permitted to

amuse myself, or to do anything, except occasionally to

net. If I spoke, Aunt Esther would say with a satirical smile,

"As if you ever could say anything worth hearing, as

if it was ever possible that any one could want to hear

what you have to say. If I took up a book, I was told instantly

to put it down again, it was "disrespect to my Uncle."

If I murmured, Aunt Esther, whose temper was absolutely

unexcitable, quelled it by her icy rigidity. Thus gradually I got

into the habit of absolute silence at the Rectory-a habit which

it took me years to break through: and I often still suffer from

the want of self-confidence engendered by reproaches and taunts

which never ceased: for a day-for a week-for a year they would

have been nothing: but for always, with no escape but my

own death or that of my tormentor! Water dripping for ever on a

stone wears through the stone at last.

the cruelty which I

received from my new aunt was repeated in various forms by her

sisters, one or other of whom was always at the Rectory. Only

Priscilla, touched by the recollection of many long visits during

my childhood at Lime, occasionally sent a kindly message or spoke

a kindly word to me from her sick-bed, which I repaid by constant

offerings of flowers. Most of all, however, did I feel the

conduct of Mary Maurice, who, by pretended sympathy and affection,

wormed from me all my little secrets - how miserable my uncle's

marriage had made my home-life, how I never was alone with my

mother now, &c.-and repeated the whole to Aunt Esther.

From this time Aunt Esther

resolutely set herself to subdue me thoroughly-to make me feel

that any remission of misery at home, any comparative comfort,

was as a gift from her. But to make me feel this thoroughly, it

was necessary that all pleasure and comfort in my home should

first be annihilated. I was a very delicate child, and suffered

absolute agonies from chilblains, which were often large open

wounds on my feet. Therefore I was put to sleep in "the

Barracks" - two dismal unfurnished, uncarpeted north rooms,

without fireplaces, looking into a damp courtyard, with a well

and a howling dog. My only bed was a rough deal trestle, my only

bedding a straw palliasse, with a single coarse blanket. The only

other furniture in the room was a deal chair, and a washing-basin

on a tripod. No one was allowed to bring me any hot water; and as

the water in my room always froze with the intense cold, I had to

break the ice with a brass candlestick, or, if that were taken

away, with my wounded hands. If, when I came down in the morning,

as was often the case, I was almost speechless from sickness and

misery, it was always declared to be "temper." I was

given "saur-kraut" to eat because the very smell of it

made me sick.

When Aunt Esther

discovered the comfort that I found in getting away to my dear

old Lea, she persuaded my mother that Lea's influence over me was

a very bad one, and obliged her to keep me away from her.

A favourite torment was

reviling all my own relations before me - my sister, &c. -

and there was no end to the insulting things Aunt Esther said of

them.

People may wonder, and oh!

how often have I wondered that my mother did not put an end to it

all. But, inexplicable as it may seem, it was her extraordinary

religious opinions which prevented her doing so. She literally

believed and taught that when a person struck you on the right

cheek you were to invite them to strike you on the left also, and

therefore if Aunt Esther injured or insulted me in one way, it

was right that I should give her the opportunity of injuring or

insulting me in another! I do not think that my misery cost her

nothing, she felt it acutely; but because she felt it thus,

she welcomed it, as a fiery trial to be endured. Lea, however,

was less patient, and openly expressed her abhorrence of her own

trial in having to come up to the Rectory daily to dress my

mother for dinner, and walk back to Lime through the dark night,

coming again, shine or shower, in the early morning, before my

mother was up.

I would not have any one

suppose that, on looking back through the elucidation of years, I

can see no merits in my Aunt Esther Hare. The austerities which

she enforced upon my mother with regard to me she fully carried

out as regarded herself. "Elle vivait avec elle même comme

sa victime," as Mme. de Staël would describe it. She was

the Inquisition in person. She probed and analysed herself and

the motive of her every action quite as bitterly and mercilessly

as she probed and analysed others. If any pleasure, any even

which resulted from affection for others, had drawn her for an

instant from what she believed to be the path -and it was always

the thorniest path - of self-sacrifice, she would remorselessly

denounce that pleasure, and even tear out that affection from her

heart. She fasted and denied herself in everything; indeed, I

remember that when she was once very ill, and it was necessary

for her to see a doctor, she never could be. persuaded to consent

to it, till the happy idea occurred of inducing her to do so on a

Friday, by way of a penance! To such of the poor as accepted her

absolute authority, Aunt Esther was unboundedly kind, generous,

and considerate. To the wife of the curate, who leant confidingly

upon her, she was an unselfish and heroic nurse, equally

judicious and tender, in every crisis of a perplexing and

dangerous illness. To her own sisters and other members of her

family her heart and home were ever open, with unvarying

affection. To her husband, to whom her severe creed taught her to

show the same inflexible obedience she exacted from others, she

was utterly devoted. H is requirement that she should receive his

old friend, Mrs. Alexander, as a permanent inmate, almost on an

equality with herself in the family home, and surround her with

loving attentions, she bowed to without a murmur. But to a little

boy who was, to a certain degree, independent of her, and who had

from the first somewhat resented her interference, she knew how

to be - oh! she was - most cruel.

Open war was declared at

length between Aunt Esther and myself. I had a favourite cat

called Selma, which I adored, and which followed me about at Lime

wherever I went. Aunt Esther saw this, and at once insisted that

the cat must be given up to her. I wept over it in agonies of

grief: but Aunt Esther insisted. My mother was relentless in

saying that I must be taught to give up my own way and pleasure

to others; and forced to give it up if I would not do so

willingly, and with many tears, I took Selma in a basket to the

Rectory. For some days it almost comforted me for going to the

Rectory, because then I possibly saw my idolised Selma. But soon

there came a day when Selma was missing: Aunt Esther had ordered

her to be . . . hung!

From this time I never

attempted to conceal that I loathed Aunt Esther. I constantly

gave her the presents which my mother made me save up all my

money to buy for her-for her birthday, Christmas, New Year, &c.

- but I never spoke to her unnecessarily. On these occasions I

always received a present from her in return – "The

Rudiments of Architecture," price nine-pence, in a red cover.

It was always the same, which not only saved expense, but also

the trouble of thinking. I have a number of copies of "The

Rudiments of Architecture" now, of which I thus became the

possessor.

Only from Saturday till

Monday we had a reprieve. The nearness of Lime to the school

which my mother undertook to teach on Sundays was the excuse, but,

as I see from her journal, only the excuse, which she made to

give me one happy day in the week. How well I remember still the

ecstasy of these Saturday evenings, when I was once more alone

with the mother of my childhood, who was all the world to me, and

she was almost as happy as I was in playing with my kittens or my

little black spaniel "Lewes," and when she would sing

to me all her old songs – "Hohenlinden," "Lord

Ullin's Daughter," &c. &c. - and dear Lea was able

to come in and out undisturbed, in the old familiar way.

Even the pleasures of this

home-Sunday, however, were marred in the summer, when my mother

gave in to a suggestion of Aunt Esther that I should be locked

into the vestry of the church between the services. Miserable

indeed were the three hours which - provided with a sandwich for

dinner - I had weekly to spend there; and though I did not expect

to see ghosts, the utter isolation of Hurstmonceaux Church, far

away from all haunts of men, gave my imprisonment an unusual

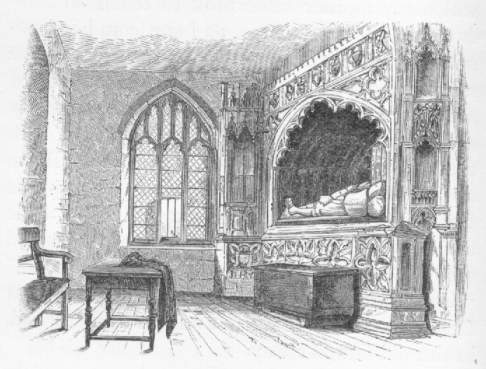

eeriness. Sometimes I used to clamber over the tomb of the Lords

Dacre, which rises like a screen against one side of the vestry,

and be stricken with vague terrors by the two grim white figures

lying upon it in the silent desolation, in which the scamper of a

rat across the floor seemed to make a noise like a whirlwind. At

that time two grinning skulls (of the founder and foundress of

the church, it was believed) lay on the ledge of the tomb; but

soon after this Uncle Julius and Aunt Esther made a weird

excursion to the churchyard with a spade, and buried them in the

dusk with their own hands. In the winter holidays, the intense

cold of the unwarmed church made me so ill, that it led to my

miserable penance being remitted. James II. used to say that

"Our Saviour flogged people to make them go out of the

temple, but that he never punished them to make them go in."5 But in my childhood no similar

abstinence was observed.

It was a sort of comfort

to me, in the real church-time, to repeat vigorously all the

worst curses in the Psalms, those in which David showed his most

appalling degree of malice (Psalm xxxv. 7-16, Psalm lix., Psalm

lxix. 22-29, Psalm cxl. 9, 10, for instance), and apply them to

Aunt Esther & Co. As all the Psalms were extolled as beatific,

and the Church of England used them constantly for edification,

their sentiments were all right, I supposed.

A great delight to me at

this time was a cabinet with many drawers which my mother

THE VESTRY,

HURSTMONCEAUX.

gave me to keep my

minerals and shells in, and above which was a little bookcase

filled with all my own books. The aunts in vain tried to persuade

her to take away "some of the drawers," so that I might

"never have the feeling that the cabinet was wholly mine."

When I returned to school, it was some amusement in my walks to

collect for this cabinet the small fossils which abound in the

Wiltshire limestone about Harnish, especially at Kellaway's

quarry, a point which it was always our especial ambition to

reach on holidays. At eleven years old I was quite learned about

Pentacrinites, Bellemnites, Ammonites, &c.

It was often a sort of

vague comfort to me at home that there was always one person at

Hurstmonceaux Rectory whom Aunt Esther was thoroughly afraid of.

It was the faithful old servant Collins, who had kept his master

in order for many years. I remember that my Uncle Marcus, when he

came to the Rectory, complained dreadfully of the tea, that the

water with which it was made was never "on the boil,"

&c. – "they really must speak to Collins about it."

But neither Uncle Julius nor Aunt Esther would venture to do it;

they really couldn't: he must do it himself. And he did it, and

very ill it was received.

The summer holidays were

less miserable than those in the winter, because then, at least

for a time, we got away from Hurstmonceaux. In the summer of 1845,

I went with my mother to her old home of Alton for the first time.

How well I remember her burst of tears as we came in sight of the

White Horse, and the church-bells ringing, and the many simple

cordial poor people coming out to meet her, and blessing her. She

visited every cottage and every person in them, and gave feasts

in a barn to all the people. One day the school-children all sang

a sort of ode which a farmer's daughter had composed to her.

Never was my sweet mother more charming than in her intercourse

with her humble friends at Alton, and I delighted in threading

with her the narrow muddy foot-lanes of the village to the

different cottages, of old and young Mary Doust, of Lizzie Hams,

Avis Wootton, Betty Perry, &c.

Alton was, and is, quite

the most primitive place I have ever seen, isolated - an oasis of

verdure - in the midst of the great Wiltshire corn-plain, which

is bare ploughed land for so many months of the year; its two

tiny churches within a stone-throw of each other, and its

thatched mud cottages peeping out of the elms which surround its

few grass pastures. A muddy chalky lane leads from the village up

to "Old Adam," the nearest point on the chain of downs,

and close by is a White Horse, not the famous beast of Danish

celebrity, but something much more like the real animal. I was

never tired during this visit of hearing from his loving people

what "Uncle Augustus" had said to them, and truly his

words and his image seemed indelibly impressed upon their hearts.

Mrs. Pile, with whose father or sister we stayed when at Alton,

and who always came to meet us there, was one of those rare

characters in middle life who are really ennobled by the

ceaseless action of a true, practical, humble Christianity. I

have known many of those persons whom the world calls "great

ladies" in later times, but I have never known any one who

was more truly "a lady" in every best and highest sense,

than Mrs. Pile.

On leaving Alton, we went

to join the Marcus Hares in the express train at Swindon. Uncle

Marcus, Aunt Lucy, her maid Griffiths, and my mother were in one

compartment of the carriage; my little cousin Lucebella, Lea, an

elderly peer (Lord Saye and Sele, I think), and I were in the

other, for carriages on the Great Western were then divided by a

door. As we neared Windsor, my little cousin begged to be held up

that she might see if the flag were flying on the castle. At that

moment there was a frightful crash, and the carriage dashed

violently from side to side. In an instant the dust was so

intense that all became pitch darkness. "For God's sake put

up your feet and press backwards; I've been in this before,"

cried Lord S., and we did so. In the other compartment all the

inmates were thrown violently on the floor, and jerked upwards

with every lurch of the train. If the darkness cleared for an

instant, I saw Lea's set teeth and livid lace opposite. I learned

then for the first time that to put hand-bags in the net along

the top of the carriage is most alarming in case of accident.

They are dashed hither and thither like so many cannon-balls. A

dressing-case must be fatal.

After what seemed an

endless time, the train suddenly stopped with a crash. We had

really, I believe, been three minutes off the line. Instantly a

number of men surrounded the carriage. "There is not an

instant to lose, another train is upon you, they may not be able

to stop it," - and we were all dragged out and up the steep

bank of the railway cutting. Most strange, I remember, was the

appearance of our ruined train beneath, lying quite across the

line. The wheels of the luggage van at the end had come off and

the rest of the train had been dragged off the line gradually,

the last carriages first. Soon two trains were waiting (stopped)

on the blocked line behind. We had to wait on the top of the bank

till a new train came to fetch us from Slough, and when we

arrived there, we found the platform full of anxious inquirers,

and much sympathy we excited, quite black and blue with bruises,

though none of us seriously hurt.

Soon after we reached

Hurstmonceaux, my Uncle Marcus became seriously ill at the

Rectory. I went with my mother, Aunt Esther, and Uncle Julius to

his "charge" at Lewes, and, as we came back in the hot

evening, we were met by a messenger desiring us not to drive up

to the house, as Uncle Marcus must not be disturbed by the sound

of wheels. Then his children were sent to Lime, and my mother was

almost constantly at the Rectory. I used to go secretly to see

her there, creeping in through the garden so as not to be

observed by the aunts, for Aunt Lucy could scarcely bear her to

be out of sight. At last one morning I was summoned to go up to

the Rectory with all the three children. Marcus went in first

alone to his father's room and was spoken to: then I went in with

the younger ones. Lucebella was lifted on to the pillow, I stood

at the side of the bed with Theodore; my mother, Uncle Julius,

and Aunt Esther

LEWES.

were at the foot. I

remember the scene as a picture, and Aunt Lucy sitting stonily at

the bed's head in a violet silk dress. My dying uncle had a most

terrible look and manner, which haunted me long afterwards, but

he spoke to us, and I think gave us his blessing. I was told that

after we left the room he became more tranquil. In the night my

mother and Uncle Julius said the "Te Deum" aloud, and,

as they reached the last verse, he died.

Aunt Lucy never saw him

again. She insisted upon being brought away immediately to Lime,

and shut herself up there. She was very peculiar at this time and

for a year afterwards, one of her odd fancies being that her maid

Griffiths was always to breakfast and have luncheon with the

family and be waited on as a lady. We children all went to the

funeral, driving in the family chariot. I had no real affection

for Uncle Marcus, but felt unusually solemnised by the tears

around me. When, however, a peacock butterfly, for which I had

always longed, actually perched upon my prayer-book as I was

standing by the open grave in the most solemn moment, I could not

resist closing the book upon it, and my prayer-book still has the

marks of the butterfly's death. I returned to school in August

under the care of Mr. Hull, a very old friend of the family, who

had come to the funeral.

To MY MOTHER

"Harnish,

August 8.-When we got to London we got a cab and went,

passing the Guildhall where Gog and Magog live, the great

Post-Office, the New Royal Exchange and the Lord Mayor's, to

Tavistock Square, where three young men rushed downstairs,

who Mr. Hull told me were his three sons - John, Henry, and

Frank. I had my tea when they had their dinner. After tea I

looked at Miss Hull's drawings. Mr. Hull gave me a book

called 'The Shadowless Man.' I stayed up to see a balloon,

for which we had to go upon the top of the house. The balloon

looked like a ball of fire. It scattered all kinds of lights,

but it did not stay up very long. We also saw a house on fire,

the flames burst out and the sky was all red.' Do give the

kitten and the kitten's kitten some nice bits from your tea

for my sake."

"August 30.

- We have been a picknick to Slaughter-ford. We all went in a

van till the woods of Slaughterford came in sight. Then we

walked up a hill, carrying baskets and cloaks between us till

we came to the place where we encamped. The dinner was

unpacked, and the cloth laid, and all sate round. When the

dishes were uncovered, there appeared cold beet bread, cheese,

and jam, which were quickly conveyed to the mouths of the

longing multitude. We then plunged into the woods and caught

the nuts by handfuls. Then I got flowers and did a sketch,

and when the van was ready we all went home. Goodbye darling

Mamma I have written a poem, which I send you-

"O

Chippenham station thy music is sweet

When the

up and down trains thy neighhourhood greet.

The up

train to London directeth our path

And the

down train will land us quite safely at Bath."

"October the

I don't know what. - O dearest Mamma, what do you think! Mr.

Dalby asked me to go to Compton Bassett with Mr. and Mrs.

Kilvert and Freddie Sheppard. . . . When we got to the gate

of a lovely rectory near Caine, Mrs. Sheppard flew to the

door to receive her son, as you would me, with two beautiful

little girls his sisters. After dinner I went with Freddie

into the garden, and to the church, and saw the peacocks and

silver pheasants, and made a sketch of the rectory. On Sunday

we had prayers with singing and went to church twice, and saw

a beautiful avenue where the ground was covered with beech-nuts.

On Monday the Dalbys' carriage brought us to Chippenham to

the Angel, where we got out and walked to Harnish. Mr. Dalby

told me to tell you that having known Uncle Augustus so well,

he had taken the liberty to invite me to Compton."

"Oct 6. -

It is now only ten weeks and six days to the holidays. Last

night I had a pan of hot water for my feet and a warm bed,

and, what was worse, two horrible pills! and this morning

when I came down I was presented with a large breakfast-cup

of senna-tea, and was very sick indeed and had a very bad

stomach-ache. But to comfort me I got your dear letter with a

sermon, but who is to preach it?"

"Nov. 6. -

Dearest Mamma, as soon as we came down yesterday all our

dresses for the fifth of November were laid out. After

breakfast the procession was dressed, and as soon as the

sentinel proclaimed that the dock struck ten, the grand

procession set out: first Gumbleton and Sheppard dressed up

with straps, cocked hats, and rosettes, carrying between them,

on a chair, Samuel dressed as Guy Fawkes in a large cocked

hat and short cloak and with a lanthorn in his hand. Then

came Proby carrying a Union Jack, and Walter (Arnold) with

him, with rosettes and bands. Then King Alick with a crown

turned up with ermine, and round his leg a blue garter.

Behind him walked the Queen (Deacon Coles) with a purple

crown and long yellow robe and train, and Princess Elizabeth

(me) in a robe and train of pink and green. After the

procession had moved round the garden, singing –

'Remember,

remember,

The

fifth of November, &c,'

the sentinel of the

guard announced that the cart of faggots was coming up the

hill . . . and in the evening was a beautiful bonfire and

fireworks.

"What a pity it

is that the new railway does not turn aside to save Lewes

Priory. I shall like very much to see the skeletons, but I

had much rather that Gundrada and her husband lay still in

their coffins, and that the Priory had not been disturbed. .

. . It is only five weeks now to the holidays."

"Nov. 28.

- Counting to the 19th, and not counting the day of breaking

up, it is now only three weeks to the holidays. I will give

you a history of getting home. From Lewes I shall look out

for the castle and the Visitation church. Then I shall pass

Ringmer, the Green Man Inn, Laugh ton, the Bat and Ball; then

the Dicker, Horsebridge, the Workhouse, the turnpike, the

turn to Carter's Corner, the turn to Magham Down, Woodham's

Farm, the Deaf and Dumb House, the Rectory on the hill, the

Mile Post – '15 miles to Lewes,' Lime Wood, the gate (oh!

when shall I be there!) - then turn in, the Flower Field, the

Beaney Field, the gate - oh! the garden - two figures

- John and Lea, - perhaps you - perhaps even the kittens will

come to welcome their master. Oh my Lime! in little more than

three weeks I shall be there!"

"Hurrah for

Dec. 1. - On Wednesday it will be, not counting breaking-up

day, two weeks, and oh! the Wednesday after we shall say 'one

week.' This month we break up! I dream of nothing, think of

nothing, but coming home. To-day we went with Mr. Walker (the

usher) to Chippenham, and saw where Lea and I used to go to

sit on the wooden bridge. . . . Not many more letters! not

many more sums!"

How vividly, how acutely,

I recollect that - in thy passionate devotion to my mother - I

used, as the holidays approached, to conjure up the most vivid

mental pictures of my return to her, and appease my longing with

the thought, of how she would rush out to meet me, of her

ecstatic delight, &c.; and then how terrible was the bathos

of the reality, when I drove up to the silent door of Lime, and

nobody but Lea took any notice of my coming; and of the awful

chill of going into the drawing-room and seeing my longed-for and

pined-for mother sit still in her chair by the fire till I went

up and kissed her. To her, who had been taught always to curtsey

not only to her father, but even to her father's chair, it was

only natural; but I often sobbed myself to sleep in a little-understood

agony of anguish - an anguish that she could not really care for

me.

"Oh, the

little more, and how much it is I

And the

little less, and what worlds away!"6

In the winter of 1845-46,

"Aunt Lucy" let Rockend to Lord Beverley, and came to

live at Lime for six months with her three children, a governess,

and two, sometimes three, servants. As she fancied herself poor,

and this plan was economical, it was frequently repeated

afterwards. On the whole, the arrangement was satisfactory to me,

as though Aunt Lucy was excessively unkind to me, and often did

not speak a single word to me for many weeks together, and though

the children were most tormenting, Aunt Esther - a far greater

enemy - was at least kept at bay, for Aunt Lucy detested her

influence and going to the Rectory quite as cordially as I did.

How often I remember my

ever-impatient rebellion against the doctrine I was always taught

as fundamental - that my uncles and aunts must be always right,

and that to question the absolute wisdom and justice of their

every act - to me so utterly selfish - was typical of the meanest

and vilest nature. How odd it is that parents, and still more

uncles and aunts, never will understand, that whilst they are

criticising and scrutinising their children or nephews, the

latter are also scrutinising and criticising them. Yet so it is

investigation and judgment of character is usually mutual. During

this winter, however, I imagine that the aunts were especially

amiable, as in the child's play which I wrote, and which we all

acted – "The Hope of the Katzekoffs" - they, with

my mother, represented the three fairies "Brigida, Rigida,

and Frigida" Aunt Lucy, I need hardly say, being Frigida,

and Aunt Esther Rigida.

Being very ill with the

measles kept me at home till the middle of February. Aunt Lucy's

three children also had the measles, and were very ill; and it is

well remembered as characteristic of Aunt Esther, that she said

when they were at the worst - "I am very glad they

are so ill: it is a well-deserved punishment because their mother

would not let them go to church for fear they should catch it

there." Church and a love of church was the standard by

which Aunt Esther measured everything. In all things she had the

inflexible cruelty of a Dominican. She would willingly and

proudly undergo martyrdom herself for her own principles, but she

would torture without remorse those who differed from her.

When we were recovering,

Aunt Lucy read "Guy Mannering" aloud to us. It was

enchanting. I had always longed beyond words to read Scott's

novels, but had never been allowed to do so – "they

were too exciting for a boy!" But usually, as Aunt Lucy and

my mother sat together, their conversation was almost entirely

about the spiritual things in which their hearts, their mental

powers, their whole being were absorbed. The doctrine of Pascal

was always before their minds – "La vie humaine n'est

qu'une illusion perpetuelle," and their treasure was truly

set in heavenly places. They would talk of heaven in detail just

as worldly people would talk of the place where they were going

for change of air. At this time, I remember, they both wished no,

I suppose they only thought they wished - to die: they talked of

longing, pining for "the coming of the kingdom," but

when they grew really old, when the time which they had wished

for before was in all probability really near, and when they were,

I believe, far more really prepared for it, they ceased to wish

for it. "By-and-by" would do. I imagine it is always

thus.

Aunt Lucy loved her second

boy Theodore much the best of her three children, and made the

greatest possible difference between him and the others. I

remember this being very harshly criticised at the time; but now

it seems to me only natural that in any family there must be

favourites. It is with earthly parents as Dr. Foxe said in a

sermon about God, that "though he may love all his children,

he must have an especial feeling for his saints."

To MY MOTHER.

"March 13.

- My dearest, dearest Mamma, to-day is my 12th birthday. How

well I remember many happy birthdays at Stoke, when before

breakfast I had a wreath of snowdrops, and at dinner a little

pudding with my name in plums. . . . I will try this new year

to throw away self and think less how to please it. Good-bye

dear Mamma."

In March the news that my

dear (Mary) Lea was going to marry our man-servant John Gidman

was an awful shock to me. My mother might easily have prevented

this (most unequal) marriage, which, as far as Mrs. Leycester was

concerned, was an elopement. It was productive of great trouble

to us afterwards, and obliged me to endure John Gidman, to wear

him like a hair-shirt, for forty years. Certainly no ascetic

torments can be so severe as those which Providence occasionally

ordains for us. As for our dear Lea herself, her marriage brought

her misery enough, but her troubles always stayed in her heart

and never filtered through. As I once read in an American novel,

"There ain't so much difference in the troubles on this

earth, as there is in the folks that have to bear them."

To My MOTHER.

"March 20.

- O my very dearest Mamma. What news! what news! I cannot

believe it! and yet sometimes I have thought it might happen,

for one night a long time ago when I was sitting on Lea's lap-O

what shall I call her now? may I still call her Lea? Welt one

night a long time ago, I said that Lea would never marry, and

she asked why she shouldn't, and said something about –

'Suppose I marry John.' . . . I was sure she could never

leave us. I put your letter away for some time till Mrs.

Kilvert sent me upstairs for my gloves. Then I opened it, and

the first words I saw were 'Lea - married.' I was so

surprised I could not speak or move. . . . How very odd it

will be for Lea to be a bride. Why, John is not half so old

as Lea, is he? . . . Tell me all about the wedding-every

smallest weeest thing - What news! what news!"

MARY (LEA) GIDMAN to

A. J. C. H.

"Stoke, March 29,

1846. - My darling child, a thousand thanks for your dear

little letter I hope the step I have taken will not displease

you. If there is anything in it you don't like, I must humbly

beg your pardon. I will give you what account I can of the

wedding. Your dear Mamma has told you that she took me to

Goldstone. Then on Saturday morning a little after nine my

mother's carriage and a saddle-horse were brought to the gate

to take us to Cheswardine. My sister Hannah and her husband

and George Bentley went with me to church. I wished you had

been with me so very much, but I think it was better that

your dear Mamma was not there, for very likely it would have

given her a bad headache and have made me more nervous than I

was, but I got through all of it better than I expected I

should. As soon as it was over the bells began to ring. We

came back to Goldstone, stayed about ten minutes, then went

to Drayton, took the coach for Whitmore, went by rail to

Chelford, and then we got a one-horse fly which took us to

Thornycroft to John's grandfather's, where we were received

with much joy. We stayed there till Wednesday, then went for

one night to Macclesfield, and came back to Goldstone on

Thursday and stayed there till Friday evening. Then we came

back to Stoke. The servants received us very joyfully, and

your dear Mamma showed me such tender feelings and kindness,

it is more than I can tell you now. My dear child, I hope you

will always call me Lea. I cannot bear the thought of your

changing my name, for the love I have for you nothing can

ever change. My mother and Hannah wish you had been in the

garden with me gathering their flowers, there is such a

quantity of them. . . . We leave Stoke to-morrow, and on

Friday reach your and our dear Lime. I shall write to you as

soon as we get back, and now goodbye, my darling child, from

your old affectionate nurse Lea."

The great age of my dear

Grandfather Leycester, ninety-five, had always made his life seem

to us to hang upon a thread, and very soon after I returned home

for my summer holidays, we were summoned to Stoke by the news of

his death. This was a great grief to me, not only because I was

truly attached to the kind old man, but because it involved the

parting with the happiest scenes of my childhood, the only home

in which I had ever been really happy. The dear Grandfather's

funeral was very different from that which I had attended last

year, and I shed many tears by his grave in the churchyard

looking out upon the willows and the shining Terne. Afterwards

came many sad partings, last visits to Hawkestone, Buntingsdale,

Goldstone; last rambles to Heishore, Jackson's Pool, and the

Islands; and then we all came away-my Uncle Penrhyn first, then

Aunt Kitty, then my mother and Lea and I, and lastly Grannie, who

drove in her own carriage all the way to her house in New Street,

Spring Gardens, the posting journey, so often talked of actually

taking place at last. Henceforward Stoke seemed to be transferred

to New Street, which was filled with relics of the old Shropshire

Rectory, and where Mrs. Cowbourne, Margaret Beeston, Anne Tudor,

and Richard the footman, with Rose the little red and white

spaniel, were household inmates as before.

I thought the house in New

Street charming - the cool, old-fashioned, bow-windowed rooms,

which we should now think very scantily furnished, and like those

of many a country inn the dining-room opening upon wide leads,

which Grannie soon turned into a garden; the drawing-room, which

had a view through the trees of the Admiralty Garden to the

Tilting Yard, with the Horse Guards and the towers of Westminster

Abbey.

The grief of leaving Stoke

made me miserably unwell, and a doctor was sent for as soon as I

arrived at the Stanleys' house, 38 Lower Brook Street, who came

to me straight from a patient ill with the scarlatina, and gave

me the disorder. For three weeks I was very seriously ill in hot

summer weather, in stifling rooms,

REV. O.

LEYCESTER'S GRAVE, STOKE CHURCHYARD.

looking on the little

black garden and chimney-pots at the back of the house. Mary and

Kate Stanley were sent away from the infection, and no one came

near me except my faithful friend Miss Clinton, who brought me

eau-de-Cologne and flowers. It was long foolishly concealed from

me that I had the scarlatina, and therefore, as I felt day after

day of the precious holidays ebbing away, while I was pining for

coolness and fresh country air, my mental fever added much to my

bodily ailments, whereas, when once told that I was seriously ill,

I was quite contented to lie still. Before I quite recovered, my

dear nurse Lea became worn-out with attending to me, and we had

scarcely reached Lime before she became most dangerously ill with

a brain-fever For many days and nights she lay on the brink of

the grave, and great was my agony while this precious life was in

danger. Aunt Esther, who on great occasions generally

behaved kindly, was very good at this time, ceased to persecute

me, and took a very active part in the nursing.

At length our dear Lea was

better, and as I was still very fragile, I went with my mother

and Anne Brooke, our cook, to Eastbourne-then a single row of

little old-fashioned houses by the sea-where we inhabited, I

should think, the very smallest and humblest lodging that ever

was seen. I have often been reminded of it since in reading the

account of Peggotty's cottage in "David Copperfield."

It was a tiny house built of flints, amongst the boats, at the

then primitive end of Eastbourne, towards the marshes, and its

miniature rooms were filled with Indian curiosities, brought to

the poor widow to whom it belonged by a sailor son. The Misses

Thomas of Wratton came to see us here, and could hardly suppress

their astonishment at finding us in such a place - and when the

three tall smart ladies had once got into our room, no one was

able to move, and all had to go out in the order in which they

were nearest the door. But my mother always enjoyed exceedingly

these primitive places, and would sit for hours on the beach with

her Taylor's "Holy Living" or her "Christian Year,"

and had soon made many friends amongst the neighbouring cottagers,

whose houses were quite as fine as her own, and who were

certainly more cordial to the lady who had not minded settling

down as one of themselves, than they would have been to a smart

visitor in a carriage. The most remarkable of these people was an

excellent old woman called Deborah Pattenden, who lived in the

half of a boat. turned upside down, and had had the most

extraordinary adventures. My first literary work was her

biography, which told how she had suffered the pains of drowning,

burning (having been enveloped in flames while struck by

lightning), and how she had lain for twenty-one days in a rigid

trance (from "the plague," she described it) without

food or sign of life, and was near being buried alive. We found a

transition from our cottage life in frequent visits to Compton

Place, where Mrs. Cavendish, mother of the 7th Duke of Devonshire,

lived then, with her son Mr. Cavendish, afterwards Lord Richard.

She was a charming old lady, who always wore white, and had very

simple and very timid manners. But she was fond of my mother, who

was quite adored by Lord Richard, by whom we were kept supplied

with the most beautiful fruits and flowers of the Compton Gardens.

He was very kind to me also, and would sometimes take me to his

bookcases and tell me to choose any book I liked for my own. We

seldom afterwards passed a summer without going for a few days to

Compton Place as long as Mrs. Cavendish lived there. It was there

that I made my first acquaintance with the existence of many

simple luxuries to which, in our primitive life, we were quite

unaccustomed, but which in great houses are considered almost as

necessaries. The Cavendishes treated us as distant relations, in

consequence of the marriage of my Grandmother's cousin, Georgiana

Spencer, with the 5th Duke of Devonshire.

When I returned to Harnish

I was still wretchedly ill, and the constant sickness under which

I suffered, with the extreme and often unjust severity of Mr.

Kilvert, made the next half year a very miserable one. In the

three years and a half which I had spent at Harnish, I had been

taught next to nothing - all our time having been frittered in

learning Psalms by heart, and the Articles of the Church of

England (I could say the whole thirty-nine straight off when

eleven years old), &c. Our history was what Arrowsmith's

Atlas used to describe Central Africa to be " a barren

country only productive of dates." I could scarcely construe

even the easiest passages of Caesar. Still less had I learned to

play at any ordinary boys' games; for, as we had no playground,

we had naturally never had a chance of any. I was glad of any

change. It was delightful to leave Harnish for good at Christmas,

1846, and the prospect of Harrow was that of a voyage of

adventure.

In January 1847 my mother

took me to Harrow. Dr. Vaughan was then headmaster, and Mr.

Simpkinson, who had been long a curate of Hurstmonceaux, and who

had been consequently one of the most familiar figures of my

childhood, was a master under him, and, with his handsome, good-humoured

sister Louisa, kept the large house for boys beyond the church,

which is still called "The Grove." It was a wonderfully

new life upon which I entered; but though a public school was a

very much rougher thing then than it is now, and though the

fagging for little boys was almost ceaseless, it would not have

been an unpleasant life if I had not been so dreadfully weak and

sickly, which sometimes unfitted me for enduring the roughness to

which I was subjected. As a general rule, however, I looked upon

what was intended for bullying as an additional "adventure,"

which several of the big boys thought so comic, that they were

usually friendly to me and ready to help me: one who especially

stood my friend was a young giant - Twisleton, son of Lord Saye

and Sele. One who went to Harrow at the same time with me was my

connection Harry Adeane,7 whose mother was Aunt Lucy's sister, Maude

Stanley of Alderley. I liked Harry very much, but though he was

in the same house, his room was so distant that we saw little of

each other; besides, my intense ignorance gave me a very low

place in the school, in the Lower Fourth Form. It was a great

amusement to write to my mother all that occurred. In reading it,

people might imagine my narration was intended for complaint, but

it was nothing of the kind: indeed, had I wished to complain, I

should have known my mother far too well to complain to her.

To MY MOTHER.

"Harrow, Jan.29,

1847. - When I left you, I went to school and came back

to pupil room, and in the afternoon had a solitary walk to

the skating pond covered with boys. . . . In the evening two

big boys rushed up, and seizing Buller (another new boy) and

me, dragged us into a room where a number of boys were

assembled. I was led into the midst. Bob Smith8 whispered to me to do as I

was bid and I should not be hurt. On the other side of the

room were cold chickens, cake, fruit, &c., and in a

corner were a number of boys holding open little Dirom's

mouth, and pouring something horrible stirred up with a

tallow-candle down his throat. A great boy came up to me and

told me to sing or to drink some of this dreadful mixture. I

did sing - at least I made a noise - and the boys were

pleased because I made no fuss, and loaded me with oranges

and cakes.

"This morning

being what is called a whole holiday, I have had to

stay in three hours more than many of the others because of

my slowness in making Latin verses. This evening Abel Smith

sent for me to his room, and asked me if I was comfortable,

and all sorts of things."

"Jan. 21.

- What do you think happened last night? Before prayers I was

desired to go into the fifth form room, as they were having

some game there. A boy met me at the door, ushered me in, and

told me to make my salaam to the Emperor of Morocco, who was

seated cross-legged in the middle of a large counterpane,

surrounded by twenty or more boys as his saving-men. I was

directed to sit down by the Emperor, and in the same way. He

made me sing, and then jumped off the counterpane, as he said,

to get me some cake. Instantly all the boys seized the

counterpane and tossed away. Up to the ceiling I went and

down again, but they had no mercy, and it was up and down,

head over heels, topsy-turvy, till some one called out 'Satus'

- and I was let out, very sick and giddy at first, but soon

all right again. . . . I am not much bullied except by

Davenport, who sleeps in my room."

"Jan. 22.

- To-day it has snowed so hard that there has been nothing

but snow-balling, and as I was coming out of school, hit by a

shower of snowballs, I tumbled the whole way down the two

flights of stairs headlong from the top to the bottom."

"Jan. 23.

- Yesterday I was in my room, delighted to be alone for once,

and very much interested in the book I was reading, when D.

came in and found the fire out, so I got a good licking. He

makes me his fag to go errands, and do all he bids me, and if

I don't do it, he beats me, but I don't mind much. However, I

have got some friends, for when I refused to do my week-day

lessons on a Sunday, and was being very much laughed at for

it, some one came in and said, 'No, Hare, you're quite right;

never mind being laughed at.' However I am rather lonely

still with no one to speak to or care about me. Sometimes I

take refuge in Burroughs' study, but I cannot do that often,

or he would soon get tired of me. I think I shall like

Waldegrave,9 a new boy who

has come, but all the others hate him. Blomfield10 is a nice boy,

but his room is very far away. Indeed, our room is so

secluded, that it would be a very delightful place if D. did

not live in it. In playtime I go here, there, and everywhere,

but with no one and doing nothing. Yet I like Harrow very

much, though I am much teased even in my form by one big boy,

who takes me for a drum, and hammers on my two sides all

lesson-time with doubled fists. However, Miss Simmy says, if

you could see my roses you would be satisfied."

"Jan. 30.

- There are certain fellows here who read my last letter to

you, and gave me a great lecture for mentioning boys' names;

but you must never repeat what I say: it could only get me

into trouble. The other night I did a desperate thing. I

appealed to the other boys in the house against D. Stapleton

was moved by my story, and Hankey and other boys listened.

Then a boy called Sturt was very much enraged at D., and

threatened him greatly, and finally D., after heaping all the

abuse he could think of upon me, got so frightened that he

begged me to be friends with him. I cannot tell you how I

have suffered and do suffer from my chilblains, which have

become so dreadfully bad from going out so early and in all

weathers."

"Feb. 2.

- To-day, after half-past one Bill I went down the town with

Buller and met two boys called Bocket and Lory. Lory and I,

having made acquaintance, went for a walk. This is only the

second walk I have had since I came to Harrow. I am

perpetually 'Boy in the House.'"

"Feb. 10.

- To-day at 5 minutes to 11, we were all told to go into the

Speech-room (do you remember it?), a large room with raised

benches all round and a platform in the middle and places for

the monitors. I sat nearly at the top of one of these long

ranges. Then Dr. Vaughan made a speech about snow-balling at

the Railway Station (a forbidden place), where the engine-drivers

and conductors had been snow-balled, and he said that the

next time, if he could not find out the names of the guilty

individuals, the whole school should be punished. To-day the

snow-balling, or rather ice-balling (for the balls are so

hard you can hardly cut them with a knife), has been terrific:

some fellows almost have their arms broken with them."

"Feb. 12.

- I am in the hospital with dreadful pains in my stomach. The

hospital is a large room, very quiet, with a window looking

out into the garden, and two beds in it. Burroughs is in the

other bed, laid up with a bad leg. . . . Yesterday, contrary

to rule, Dr. Vaughan called Bill, and then told all the

school to stay in their places, and said that he had found

the keyhole of the cupboard in which the rods were kept

stopped up, and that if he did not find out before one o'clock

who did it, he would daily give the whole school, from the

sixth form downwards, a new pun. of the severest kind. . . .

There never was anything like the waste of bread here, whole

bushels are thrown about every day, but the bits are given to

the poor people. . I like Valletort11 very much, and

I like Twisleton,12 who is one of

the biggest boys in this house."

"Feb. 20.-To-day

I went to the Harrisites' steeplechase. Nearly all the school

were there, pouring over hedges and ditches in a general rush.

The Harrisites were distinguished by their white or striped

pink and white jackets and Scotch caps, and all bore flags."

"Feb. 21.

- I have been out jumping and hare-and-hounds, but we have

hard work now to escape from the slave-drivers for racket-fagging.

Sometimes we do, by one fellow sacrificing himself and

shutting up the others head downwards in the turn-up

bedsteads, where they are quite hidden; and sometimes I get

the old woman at the church to hide me in the little room

over the porch till the slave-drivers have passed."

"March 1.

- I have just come back from Sheen, where I have had a very

happy Exeat. Uncle Norwich gave me five shillings, and Uncle

Penrhyn ten."

MRS STANLEY to HER

SISTER MRS. A. HARE.

"Sheen, March

1. - I never saw Augustus look anything like so well -

and it is the look of health, ruddy and firm, and his face

rounder. The only thing is that he stoops, as if there were

weakness in the back, but perhaps it is partly shyness, for I

observed he did it more at first. He did look very shy the

first day-hung his head like a snowdrop, crouched out of

sight, and was with difficulty drawn out; but I do not think

it is at all because he is cowed, and he talked more

yesterday. The Bishop was very much pleased with him, and

thought him much improved. . . . He came without either

greatcoat or handkerchief; but did not appear to want the one,

and had lost the other He said most decidedly that he was

happy, far happier than at Mr. Kilvert's, happier than he

expected to be; and, though I felt all the time what an

uncongenial element it must be, he could not be in it under

better circumstances."

To MY MOTHER.

"March 4.

- As you are ill, I will tell you my adventure of yesterday

to amuse you. I went out with a party of friends to play at

hare-and-hounds. I was hare, and ran away over hedges and

ditches. At last, just as I jumped over a hedge, Macphail

caught me, and we sat down to take breath. Just then Hoare

ran up breathless and panting, and threw himself into the

hedge crying out, 'We are pursued by navvies.' The next

minute, before I could climb back over the hedge, I found

myself clutched by the arm, and turning round, saw that a

great fellow had seized me, and that another had got Macphail

and another Hodgson Junior. They dragged us a good way, and

then stopped and demanded our money, or they would have us

down and one should suffer for all. Macphail and Hoare were

so frightened that they gave up all their money at once, but

I would not give up mine. At last they grew perfectly furious

and declared they would have our money to buy beer. I

then gave them a shilling, but hid the half-sovereign I had

in my pocket, and after we had declared we would not give

them any more, they went away.

"To cut the

story short, I got Hodgson Junior (for the others were afraid)

to go with me to the farmer on whose land the men were

working, and told what had happened. He went straight to the

field where the navvies were and - made them give up all our

money, - turned one out of his service, and threatened the

other two, and we came back to Harrow quite safe, very glad

to have got off so well.

"What do YOU

think! the fever has broken out in Vaughan's, and if any

other house catches it, we are to go-home!"

"March 9.

- All the school is in an uproar, for all Vaughan's house

went down yesterday. Two boys have the fever, and if any one

else catches it, we shall all go home. What fun it will be.

The fever came straight from Eton with some velocipedes.

Everybody now thinks everybody else has the fever I am

shunned by all because I have a sore throat, and half-a-yard

is left on each side of me in form. Boys suck camphor in

school. Endless are the reports. 'Pember's got the fever.'

– 'No, he hasn't.' - 'Yes, he has, for it's broke out in

Harris's.' – 'Then we shall all go home. Hurrah !'

– 'No, it's all a gull!'"

"My 'adventure'

with the navvies has been a very good thing for me, as some

fellows say 'that little Hare has really got some pluck.'"

"March 10.

- Hurrah! Vaughan has caught the fever. The Vaughanites are

all gone. Valletort is gone. Waldegrave is gone. But the

great news is we all go home the day after to-morrow. Now if

you don't write the instant you get this you will delay my

return home. So pray, Mamma, do-do-do-do. I cannot write much,

for the school is so hurry-scurry. There will be no Trial-oh

hip! hip! Oh pray do write directly! I shall see you soon.

Hurrah !"

(After Easter

holidays), "April 14.-When I got here, I found

Davenport was gone and Dirom come into our room. The bells

rang all night for the return of the school. We are busy at

our Trial, which we do with our masters in form. We did Ovid

this morning, and I knew much more about it than many other

fellows."

"Saturday. -

To-day has been a whole holiday, as it always is at the

end of Trial. I have got off very well, and learnt eighty

lines more than I need have done, for we need only have

learnt fifty lines, and I knew more of other things than many

others.

"To-day was 'Election

Day' - commonly called Squash Day (oh, how glad I am it is

over), the day most dreaded of all others by the little boys,

when they get squashed black and blue, and almost turned

inside out. But you won't understand this, so I will tell you.

Platt, horrid Platt, stands at one side of Vaughan's desk in

school, and Hewlett at the other, and read the names. As they

are read, you go up and say who you vote for as cricket-keeper,

and as you come out, the party you vote against squash you,

while your party try to rescue you. Sometimes this lasts a

whole hour (without exaggeration it's no fun), but to-day at

breakfast the joyful news came that the fourth form was let

off squash. It was such a delight. The fifth form were

determined that we should have something though, for as we

came out of Bill they tried to knock our hats to pieces, and

ourselves to pieces too."

"April 24.

- The boys have all begun to wear straw-hats and to buy

insect-nets, for many are very fond of collecting insects,

and to my delight I found, when I came up, that they did not

at all despise picking primroses and violets."

"April 28.

- The other day, as Sturt was staying out, I had to fag in

his place. I had to go to that horrid Platt at Ben's. At the

door of Ben's was P__________. I asked him which was Platt's

room, and he took me upstairs and pushed me into a little

dark closet, and when I got out of that, into a room where a

number of fellows were at tea, and then to another. At last I

came to some stairs where two boys were sitting crosslegged

before a door. They were the tea-fags. I went in, and there

were Platt and his brother, very angry at my being late, but

at last they let me go, or rather I was kicked out of the

house.

"To-day we went

to hear a man read the 'Merchant of Venice' in Speech-room.

Such fun: I liked it so much."

"May 1. -

Yesterday I was in a predicament. Hewlett, the head of our

house, sent me with a note to Sporling, the head of the

school in Vaughan's new house. I asked a boy which was

Sporling's. He told me that I should find him upstairs, so I

went up stairs after stairs, and at the top were two monitors,

and as I looked bewildered by the long passages, they told me

which was Sporling's room. When I came out with an' answer to

the note, they called after me, and ordered me to give

Hewlett their compliments, and tell him not to be in too

great a hurry to get into Sporling's shoes. You must obey a

monitor's orders, and if you don't you get a wapping; but I

was pretty sure to get a wapping anyway-from the monitors if

I did not deliver the message, and from Hewlett for its

impertinence. I asked a great many boys, and they all said I

must tell Hewlett directly. At last I did he was in a great

rage, but said I might go.

"I have 7s. 6d.

owed me, for as soon as the boys have any money they are

almost obliged to lend it; at least you never have any peace

till it is all gone. Some of the boys keep rabbits in the

wells of their studies, but to-night Simmy has forbidden this."

"June. - On

Sunday in the middle of the Commandments it was so hot in

chapel that Kindersley fell down in a fit. He was seized head

and foot and carried out, struggling terribly, by Smith and

Vernon and others: and the boys say that in his fit he seized

hold of Mr. Middlemist's (the Mathematical Master's) nose and

gave it a very hard tweak; but how far this is true I cannot

tell. However, the whole chapel rose up in great

consternation, some thinking one thing and some another, and

some not knowing what to think, while others perhaps thought

as I did, that the roof was coming down. Dr. Vaughan went on

reading the prayers, and Kiridersley shrieking, but at last

all was quiet. Soon, however, there was another row, for

Miles fainted, and he was carried out, and then several

others followed his example. That night was so hot that many

of the boys slept on the bare floor, and had no bedclothes on,

but the next day it rained and got quite cold, and last night

we were glad of counterpanes and blankets again."

"The Bishop's

Holiday. - The cricket-fagging, the dreadful,

horrible cricket-fagging comes upon me today. I am Boy in the

House on the extra whole holiday, and shall have cricket-fagging

in the evening at the end of a hard day's other fagging."

"Saturday. -

I must write about the awful storm of last night. I

had been very ill all day) and was made to take a powder in

marmalade - Ah-h-bah! - and went to sleep about twelve with

the window wide open because of the heat. At half-past two I

awoke sick, when to my astonishment, it being quite dark,

flash after flash of lightning illuminated the room and

showed how the rain was pouring in floods through the open

window. The wind raged so that we thought it would blow the

house down. We heard the boys downstairs screaming out and

running about, and Simmy and Hewlett trying to keep order. I

never saw such a storm. All of a sudden, a long loud clap of

thunder shook the house, and hail like great stones mingled

with the rain came crashing in at the skylights. Another

flash of lightning illuminated the room, and continued there

(I suppose it must have struck something) in one broad flame

of light, bursting out like flames behind the window: I

called out 'Fire, fire, the window's on fire.' This woke

Buller, who had been sleeping soundly all this time, and he

rushed to the window and forced it down with the lightning

full in his eyes. Again all was darkness, and then another

flash showed what a state the room was in-the books literally

washed off the table, and Forster and Dirom armed with foot-pans

of water Then I threw myself on my bed in agonies of sickness:

not a drop of water was to be had to drink: at last Buller

found a little dirty rain-water, and in an instant I was

dreadfully sick. . . . You cannot think what the heat was, or

what agonies of sickness I was in."13

"June 13.

- I have cricket-fagged. Maude, my secret helper in

everything, came and told me what to do. But one ball came

and I missed it, then another, and I heard every one say, 'Now

did you see that fool; he let a ball pass. Look. Won't he get

wapped!' I had more than thirty balls and missed all but one-yet

the catapulta was not used. I had not to throw up to any

monitors; Platt did not come down for some time, and I had

the easiest place on the cricket-field, so it will be much

worse next time. Oh, how glad I was when half-past eight came!

and when I went to take my jacket up, though I found it

wringing wet with dew.

"The next day

was Speech-day, but, with my usual misfortune, I

was Boy in the House. However I got off after one o'clock.

All the boys were obliged to wear straw-coloured or lavender

kid-gloves and to be dressed very smart. . . . When the

people came out of Speeches, I looked in vain for Aunt Kitty,