IN NORWAY

THE weather changed to a cloudless sunshine, which hatched all the mosquitoes, as we entered Norway in the second week in July, and the heat was so intense that, in the long railway journey from Stockholm, we were very thankful for the little tank of iced water with which each railway carriage is provided. We were disappointed in Kristiania, which is a very dull place. The town was built by Christian IV. of Denmark, and has a good central church of his time, but it is utterly unpicturesque. In the picture gallery are several noble works of Tidemann, the special painter of expression and pathos. As a companion for life is the memory of a picture which represents the administration of the last sacrament to an old peasant, whose wife's grief is turned to resignation, which ceases even to have a wish for his retention, as she beholds the heaven-born comfort with which he is looking into an unknown future. Another of the finest works of the artist represents the reception of the sacrament by a convict, young and deeply repentant, before his execution.

There is no striking scenery in the environs of Kristiania, but they are wonderfully pretty. From the avenues upon the ramparts you look down over the broad expanse of the fyord, with low blue mountain distances. Little steamers dart backwards and forwards, and convey visitors in a few minutes across the bay to Oscars Halle, a tower and small country villa of the king on a wooded knoll.

We went by the railway which winds high amongst the hills to Kongsberg, a mining village in a lofty situation. Here, in a garden of white roses, there is a most comfortable small hotel kept by a Dane, which is a capital starting-point for all expeditions in Telemarken. There is a pretty waterfall near the village, and the church should be visited, for the sake of its curious pulpit hour-glass - indeed, four glasses - quarter, half-hour, three-quarters, hour - and the top of a stool let into the wall with an inscription saying that Mr. Jacobus Stuart, King of Scotland (James I. of England), sate upon it, Nov. 25, 1589, to hear a sermon preached by Mr. David Lentz, 'between 11 and 12,' on 'The Lord is my Shepherd.'

We engaged a carriage at Kongsberg for the excursion to Tinoset, whence we arranged to go on to the Ryukan Foss, said to be the highest waterfall in Europe. We do not advise future travellers without unlimited time to follow us in the latter part of the expedition by the lake, but the carriage excursion is quite enchanting. What an exquisite drive it is through the forest - the deep ever-varying woods of noble pines and firs springing from luxuriant thickets of junipers, bilberries, and cranberries! The loveliest mountain flowers grow in these woods - huge lark-spurs of rank luxuriant foliage and flowers of faint dead blue; pinks and blue lungworts and orchids; stagmoss wreathing itself round the grey rocks, and delicate, lovely soldanella drooping in the still recesses.

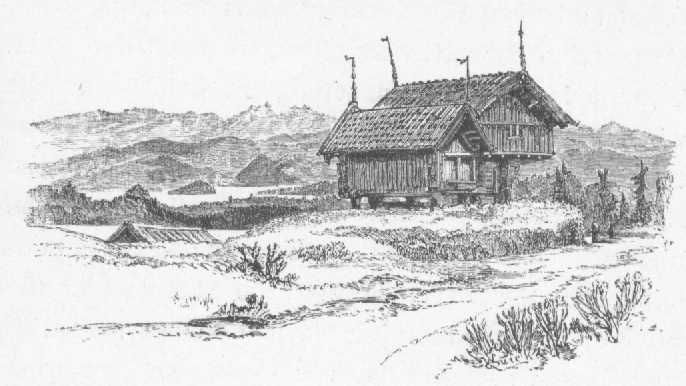

Our midday halt was at Bolkesjö, where the forest opens to green lawns, hill-set, with a charming view down the smooth declivities to a many-bayed lake, with mountain distances. Here, amid a group of old brown farm-buildings covered with rude paintings and sculpture, is a farmhouse, inhabited by the same family through many generations. It is one of the 'stations' where it is part of the duty of the farmer or 'bonder' who is owner of the soil to find horses for the use of travellers. These horses are supplied at a very trifling charge, and are brought back by a boy who sits behind the carriole or carriage upon the portmanteau: but as the horses, when not called for, are turned loose or used by the bonder in his own farm or field work, travellers generally have to wait a long time while they are caught or sent for They order their horses 'strax' – directly - one of the first words an Englishman learns to use on entering Norway, yet they scarcely ever appear before half an hour, so that Norwegians repeat with amusement the story of an Englishman who, when he wished to spend an hour at a station, ordered his horses 'after two strax's.' These halts are not always congenial to English impatience, yet they give opportunities of becoming acquainted with Norwegian life and people which can be obtained in no other way, and recollection will oftener go back to the quiet time spent in waiting for horses amid the grey rocks above some foaming streamlet, in the green oases surrounded by forest, or in clean-boarded rooms strewn with fresh fir foliage, than to the more established sights of Norway. Most delicious indeed were the two hours which we passed at Bolkesjö, in the high pastures where the peasants were mowing the tall grass ablaze with flowers, and the mountains were throwing long purple shadows over the forest, and the wind blowing freshly from the gleaming lake - and then, most delicious was the well-earned meal of eggs and bacon, strawberries and cream, and other homely dainties in the farmhouse where the beams and furniture were all painted and carved with mottoes and texts, and the primitive box-beds had crimson satin quilts. Portraits sent by well-pleased royal visitors hung on the walls side by side with common-coloured scripture prints, like those which are found in English cottages. The cellar is under a bed, beneath which it was funny to see the old farmeress disappear as she went down to fetch up for us her home-brewed ale.

BOLKESJÖ.

With the cordial 'likkelie reise' of our old hostess in our ears we left Bolkesjö full of pleasant thoughts. But what roads, or rather what want of roads, lead to Tinoset! - there were banks of glassy rock, up which our horses scrambled like cats; there were awful moments when everything seemed to come to an end, and when they gathered up their legs, and seemed to fling themselves down headlong with the carriage on the top of them, and yet we reached the bottom of the abyss buried in dust, to rise gasping and gulping and wondering we were alive, to begin the same pantomime over again.

Late in the evening, long after the sunlight had faded, and when the forests seemed to have gone to sleep and all sounds were silent we reached Tinoset. The inn is a wooden chalet on the banks of a lake with a single great pine-tree close to the door. It was terribly crowded, and the little wooden cells were the smallest apology for bedrooms, where all through the night we heard the winds howling among the mountains, and the waves lashing the shore under the windows. In the morning the lake was covered with huge blue waves crested with foam, and we were almost sorry when the steamer came and we felt obliged to embark, because, as it was not the regular day for its passage, we had summoned it at some expense from the other end of the lake. We were thoroughly wet with the spray before we reached the little inn at Strand, with a pier where we disembarked, and occupied the rest of the afternoon in drawing the purple hills, and the road winding towards them through the old birch-trees. An excursion to the Ryukan Foss occupied the next day; a dull drive through the plain, and then an exciting skirting of horrible precipices, followed by a clamber up a mountain pathlet to a châlet, where we were thankful for our well-earned dinner of trout and ale before proceeding to the Foss, the 560-feet-high fall of a mountain torrent into a black rift in the hills - a boiling, roaring abyss of water, with drifts of spray which are visible for miles before it can be seen itself.

OLD CHURCH OF HITTERDAL.

In returning frorn Tinoset, we took the way by Hitterdal, the date-forgotten old wooden church so familiar from picture-books. It had been our principal object in coming to Norway, yet the long drive had made us so ravenous in search of food that we could only endure to stay there half an hour. The church, however, is most intensely picturesque, rising with an infinity of quaintest domes and spires, all built of timber, out of a rude cloister painted red, the whole having the appearance of a very tall Chinese pagoda, yet only measuring altogether 84 feet by 57. The belfry, Norwegian-wise, stands alone on the other side of the churchyard, which is overgrown with pink willow-herb. When we reached the inn, as famished as wolves in winter, we were told by our landlady that she could not give us any dinnen 'Nei, nei,' nothing would induce her - she had too much work on her hands already - perhaps, however, the woman at the house with the flag would give us some. So, hungry and faint, we walked forth again to a house which had a flag flying in front of it, where all was silent and deserted, except for a dog who received us furiously. Having pacified him, and finding the front door locked, we made good our entrance at the back, examined the kitchen, peeped into all the cupboards, lifted up the lids of all the saucepans, and not till we had searched every corner for food ineffectually, were met by the pretty, pleasant-looking young lady of the house, who informed us in excellent English, and with no small surprise at our conduct, that we had been commiting a raid upon her private residence. Afterwards we discovered a lonely farmhouse, where there had once been a flag, and where they gave us a very good dinner, ending in a great bowl of cloudberries - in which we were joined by two pleasant young ladies and their father, an old gentleman smoking an enormous long pipe, who turned out to be the Bishop of Christiansand. The house of the landamann of Hitterdal contains a relic connected with a picturesque story quaintly illustrative of ancient Scandinavian life. It is an axe, with a handle projecting beyond the blade, and curved, so that it can be used as a walking-stick. Formerly it belonged to an ancient descendant of the Kongen, or chieftains of the district, who insisted upon carrying it to church with him in accordance with an old privilege. The priest forbade the bearing of the warlike weapon into church, which so much affected the old man that he died. His son, who thought it necessary to avenge his father's death, went to the priest with the axe in his hands, and demanded the most precious thing he possessed – when the priest brought his Bible and gave it to him, open upon a passage exhorting to forgiveness of injuries.

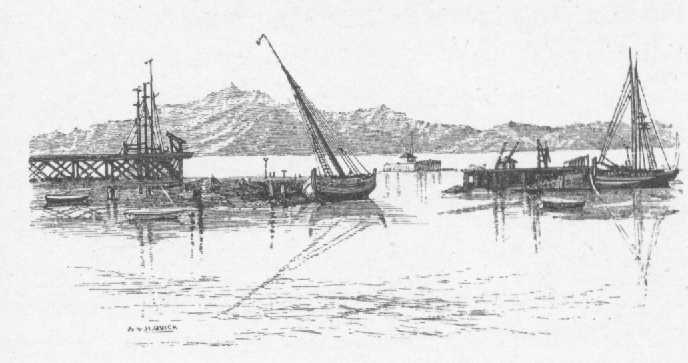

THRONDTJEM FYORD.

On July 25 we left Kristiania for Throndtjem - the whole journey of three hundred and sixty miles being very comfortable, and only costing 30 francs. The route has no great beauty, but endless pleasant variety - rail to Eidswold, with bilberries and strawberries in pretty birch-bark baskets for sale at all the railway stations; a vibrating steamer for several hours on the long, dull Miosen lake; railway again, with some of the carriages open at the sides; then an obligatory night at Koppang, a large station, where accommodation is provided for every one, but where, if there are many passengers, several people, strangers to each other, are expected to share the same room. On the second day the scenery improves, the railway sometimes running along and sometimes over the river Glommen, on a wooden causeway, till the gorge of mountains opens beyond Stören, into a rich country with turfy mounds constantly reminding us of the graves of the hero-gods of Upsala. Towards sunset, beyond the deep cleft in which the river Nid runs between lines of old painted wooden warehouses, rises the burial-place of S. Olaf, the shrine of Scandinavian Christianity, the stumpy-towered cathedral of Throndtjem. The most northern railway station and the most northern cathedral in Europe!

THRONDTJEM CATHEDRAL.

Surely the cradle of Scandinavian Christianity is one of the most beautiful places in the world! No one had ever told us about it, and we went there only because it is the old Throndtjem of sagas and ballads, and expecting a wonderful and beautiful cathedral. But the whole place is a dream of loveliness, so exquisite in the soft silvery morning light on the fyord and delicate mountain ranges, the rich nearer hills covered with bilberries and breaking into steep cliffs - that one remains in a state of transport, which is at a climax while all is engraven upon an opal sunset sky, when an amethystine glow spreads over the mountains, and when ships and buildings meet their double in the still, transparent water Each wide street of curious low wooden houses displays a new vista of sea, of rocky promontories, of woods dipping into the water; and at the end of the principal street is the grey massive cathedral where S. Olaf is buried, and where northern art and poetry have exhausted their loveliest and most pathetic fancies around the grave of the national hero.

The 'Cathedral Garden,' for so the graveyard is called, is most touching. Acres upon acres of graves are all kept - not by officials, but by the families they belong to - like gardens. The tombs are embowered in roses and honeysuckle, and each little green mound has its own vase for cut flowers daily replenished, and a seat for the survivors, which is daily occupied, so that the link between the dead and the living is never broken.

Christianity was first established in Norway at the end of the tenth century by King Olaf Trygveson, son of Trygve and of the lady Astrida, whose romantic adventures, when sold as a slave after her husband's death, are the subject of a thousand stories. When Olaf succeeded to the throne of Norway after the death of Hako, son of Sigurd, in 996, he proclaimed Christianity throughout his dominions, heard matins daily himself, and sent out missionaries through his dominions. But the duty of the so-called missionaries had little to do with teaching, they were only required to baptize. All who refused baptism were tortured and put to death. When, at one time, the estates of the province of Throndtjem tried to force Olaf back to the old religion, he outwardly assented, but made the condition that the offended pagan deities should in that case be appeased by human sacrifice - the sacrifice of the twelve nobles who were most urgent in compelling him; and upon this the ardour of the chieftains for paganism was cooled, and they allowed Olaf unhindered to demolish the great statue of Thor, covered with gold and jewels, in the centre of the province of Throndtjem, where he founded the city then called Nidares, upon the river Nid.

No end of stories are narrated of the cruelties of Olaf Trygveson. When Egwind, a northern chieftain, refused to abandon his idols, he first attempted to bribe him, but, when gentler means failed, a chafing-dish of hot coals was placed upon his belly till he died. Raude the magician had a more horrible fate: an adder was forced down a horn into his stomach, and left to eat its way out again!

The first Christian king of Norway was an habitual drunkard, and, by twofold adultery, he, the husband of Godruna, married Thyra of Denmark, the wife of Duke Borislaf of Pomerania. This led to a war with Denmark and Sweden, whose united fleets surrounded him near Stralsund. As much mystery enshrouds the story of his death as is connected with that of Arthur, Barbarossa, or Harold: as his royal vessel, the Long Serpent, was boarded by the enemy, he plunged into the sea and was no more seen, though some chroniclers say that he swam to the shore in safety and died aftenvards at Rome, whither he went on pilgrimage.

Olaf Trygveson had a godson Olaf, son of Harald Grenske and Asta, who had the nominal title of king given to all sea captains of royal descent. From his twelfth year, Olaf Haraldsen was a pirate, and he headed the band of Danes who destroyed Canterbury and murdered S. Elphege - a strange feature in the life of one who has been himself regarded as a saint since his death. By one of the strange freaks of fortune common in those times, this Olaf Haraldsen gained a great victory over the chieftain Sweyn, who then ruled at Nidaros, and, chiefly through the influence of Sigurd Syr, a great northern landowner who had become the second husband of his mother, he became seated in 1016 upon the throne of Norway. His first care was for the restoration of Christianity, which had fallen into decadence in the sixteen years which had elapsed since the defeat of Olaf Trygveson. The second Olaf imitated the violence and cruelty of his predecessor. Whenever the new religion was rejected, he beheaded or hung the delinquents. In his most merciful moments he mutilated and blinded them: 'he did not spare one who refused to serve God.' After fourteen years of unparalleled cruelties in the name of religion, he fell in battle with Canute the Great at Sticklestadt. He had abducted and married Astrida, daughter of the King of Sweden, but by her he had no children. Bv his concubine Alfhilda he left an only son, who lived to become Magnus the Good, King of Norway. There is a very fine story of the way in which Magnus obtained his name. Olaf had said, 'I very seldom sleep, and if I ever do it will be the worse for any one who awakens me.' Whilst he was asleep Alfhilda's child was born. Then the King's scald or poet and Siegfried the mass priest debated together as to whether they should awaken him. At first they thought they would then the poet said, 'No; I know him better than that: he must not be awakened.' 'That is all very well,' said the priest, 'but the child must be baptised at once. What shall we call him?' 'Oh,' said the scald, I know that the King said that the child should be named after the greatest monarch that ever lived, and his name was Magnus,' for he only remembered one part of the name. So they called him Magnus.

When the King woke up he was furious. 'Who can have dared to do this thing - to christen the child without consulting me, and to give him this outlandish name, which is no name at all - who can have dared to do it?' Then the mass priest was terrified and shrank into his shoes, but the scald answered boldly, 'I did it, and I did it because it was better to send two souls to God than one soul to the devil; for if the child had died unbaptised it would have been lost, but if you kill Siegfried and me we shall go straight to heaven.'

And then King Olaf thought he would say no more about it.

However terrible the cruelties of Olaf Haraldsen were in his lifetime, they were soon dazzled out of sight amid the halo of miracles with which his memory was encircled by the Roman Catholic Church. It was only recollected that when, according to the legend, he raced for the kingdom with his half-brother Harald,in his good ship the Ox,

Saint Olaf, who on God relied,

Three days the first his house descried;

after which

Harald so fierce with anger burned

He to a lothely dragon turned;

but because

A pious zeal Saint Olaf bore,

He long the crown of Norway wore.

His admirers narrated that when he was absently cutting chips from a stick with his knife on a Sunday, a servant passed him with the reproof, 'Sir, it is Monday to-morrow,' when he placed the sinful chips in his hand, and, setting them on fire, bore the pain till they were all consumed. It was remembered that as he walked to the church which Olaf Trygveson had founded at Nidaros, he 'wore a glory in his yellow hair.' And gradually he became the most popular saint of Scandinavia. His shirt was an object of pilgrimage in the Church of S. Victor at Paris, and many churches were dedicated to him in England, and especially in London, where Tooley Street still records his familiar appellation of S. Tooley.

It was when the devotion to S. Olaf was just beginning that Earl Godwin and his sons were banished from England for a time. Two of these, Harold and Tosti, became vikings, and, in a great battle, they vowed that, if they were victorious, they would give half the spoil to the shrine of S. Olaf and a huge silver statue, which they actually gave, existed at Throndtjem till 1500, and if it existed still would be one of the most important relics in archæology. The old Kings of Norway used to dig up the saint from time to time and cut his nails. When Harold Hardrada was going to England, he declared that he must see S. Olaf once again. 'I must see my brother once more,' he said, and he also cut the saint's nails. But he also thought that from that time it would be better that no one should see his brother any more - it would not be for the good of the Church - so he took the keys of the shrine and threw them into the fyord; at the same time, however, he said it would be good for men in after-ages to know what a great king was like, so he caused S. Olaf's measure to be engraved upon the wall in the church at Throndtjem - his measure of seven feet - and there it is still.

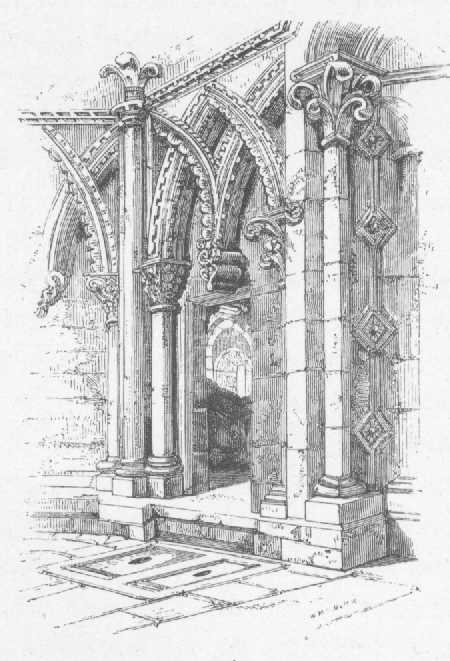

S. OLAF'S WELL.

Around the shrine of Olaf in Throndtjem, in which, in spite of Harold Hardrada, his 'incorrupt body' was seen more than five hundred years after his death, has arisen the most beautiful of northern cathedrals, originating in a small chapel built over his grave within ten years after his death. The exquisite colour of its green-grey stone adds greatly to the general effect of the interior, and to the delicate sculpture of its interlacing arches. From the ambulatory behind the choir opens a tiny chamber containing the Well of S. Olaf, of rugged yellow stone, with the holes remaining in the pavement through which the dripping water ran away when the buckets were set down. Amongst the many famous Bishops of Throndtjem, perhaps the most celebrated has been Anders Arrebo, 'the father of Danish poetry' (1587-1637), who wrote the 'Hexameron,' an extraordinarily long poem on the Creation, which nobody reads now. The cathedral is given up to Lutheran worship, but its ancient relics are kindly tended and cared for, and the building is being beautifully restored. Its beautiful Chapter House is lent for English service on Sunday's.

In the wide street which leads from the sea to the cathedral is the 'Coronation House,' the wooden palace in which the Kings and Queens of Sweden and Norway stay when they come hither to be crowned. Hither the present beloved Queen, Sophie of Nassau, came in 1873, driving herself in her own carriage from the Romsdal, in graceful compliance with the popular mode of Norwegian travel. It is because even the finest buildings in Norway are generally built of wood that there are so few of any real antiquity. Near the shore of the fyord, the custom-house occupies the site of the Orething, where the elections of twenty kings have taken place. It is sacred ground to a King of Norway, who passes it bareheaded. The familiar affection with which the Norwegians regard their sovereigns can scarcely be comprehended in any other country. To their people they are 'the father and mother of the land.' The broken Norse is remembered at Throndtjem in which King Carl Johann begged people 'to make room for their old father' when they pressed too closely upon him. When the present so beloved Queen drove herself to her coronation, the people met her with flowers at all the 'stations' where the horses were changed. 'Are you the mother of the land?' they said. 'You look nice, but you must do more than look nice; that is not the essential.' One old woman begged the lady in waiting to beg her majesty to get upon the roof of the house. 'Then we should all see her.' At Throndtjem the peasants touchingly and affectionately always addressed her as 'Du.'

In returning from Throndtjem we left the railway at Stören, where we engaged a double carriole, and a carriage for four with a pleasant boy called Johann as its driver, for the return journey. It was difficult to obtain definite information about anything, English books being almost useless from their incorrectness. and we set off with a sort of sense of exploring an unknown country. At every 'station' we changed horses, which were sent back by the boy, who perched upon the luggage behind, and we marked our distances by calling our horses after the Kings of England. Thus, setting off from Stören with William the Conqueror, we drove into the Romsdal with Edward VI. After a drive with Lady Jane Grey, we set off again with Mary. But the Kings of England failed us long before our driving days were over, and we used up all the Kings of Rome also. As we were coming down a steep hill into Lillehammer with Tarquinius Superbus, something gave way and he quietly walked out of the harness, leaving us to run briskly down-hill and subside into the hedge. We captured Tarquinius but how to put him in again was a mystery, as we had never harnessed a horse before. However, by trying every strap in turn we got him in somehow, and escaped the fate of Red Riding Hood amid the lonely hills.

For a great distance after leaving Stören there is little especially striking in the scenery, except one gorge of old weird pine-trees in a rift of purple mountains. After you emerge upon the high Dovre-Fyeld, the huge ranges of Sneehatten rise snowy, gleaming, and glorious, above the wide yellow-grey expanse, hoary with reindeer moss, though, as the Dovre-Fyeld is itself three thousand feet high, and Sneehatten only seven thousand three hundred, it does not look so high as it really is. Next to Throndtjem itself, the old ballads and songs of Norway gather most thickly around the Dovre-Fyeld. It is here that the witches are supposed to hold their secret meetings at their Blokulla, or black hill. Across these yellow hills of the Jerkin-Fyeld the prose Edda describes Thor striding to his conflict with the dragon Jormangandur 'by Sneehatten's peak of snow,' where 'the tall pines cracked like a field of stubble under his feet;' and here, according to the ancient fragment called the ballad of 'The Twelve Wizards,' as given in Prior's 'Ancient Danish Ballads' –

At Dovrefeld, over on Norways reef,

Were heroes who never knew pain or grief.

There dwelt there many a warrior keen,

The twelve bold brothers of Ingeborg queen.

The first with his hand the storm could hush

The second could stop the torrent's rush.

The third could dive in the sea as a fish;

The fourth never wanted meat on dish.

The fifth he would strike the golden lyre,

And young and old to the dancing fire.

The sixth on the horn would blow a blast,

Who heard it would shudder and stand aghast.

The seventh go under the earth could he;

The eighth he could dance on the rolling sea .

The ninth tamed all that in greenwood crept;

The tenth not a nap had ever slept.

The eleventh the grisly lindworm bound,

And will what he would, the means he found.

The twelfth he could all things understand,

Though done in a nook of the farthest land.

Their equals were never seen there in the North,

Nor anyvhere else on the face of the earth.

In spite of great fatigue from the distances to be accomplished, each days journcy in carriage or carriole has its peculiar charms, the going on and on into an unknown land, meeting no one, sleeping in odd, primitive, but always clean rooms, setting off again at half-past five or six, and halting at comfortable stations, with their ever-moderate prices and their cheery farm-servants, who kissed our hands all round on receiving the very smallest gratuity - a coin meaning twopence-halfpenny being a source of ecstatic bliss.

The 'bonders,' who keep the stations, generally themselves represent the gentry of the country, the real gentry filling the position of the English aristocracy. The bonders are generally very well off, having small tithes, good houses, boundless fuel, a great variety of food, and continual change of labour on their own small properties. Their wives, who never walk, have a sledge for winter, and a carriole and horse to take them to church in summer In the many months of snow, when the cows and horses are all stabled in the 'laave,' and when out-of-door occupations fail, they occupy the time with household pursuits - carpentering, tailoring, or brewing. When a bonder dies, his wife succeeds to his property until her second marriage; then it is divided amongst his children.

The 'stations' or farmhouses are almost entirely built of wood, but those of a superior class have a single room of stone, used only in bridals or births, a custom handed down from old times when a place of special safety was required at those seasons.

Nine-tenths of the country are covered with pine-forests, but the trees are always cut down before they grow old. We did not see a single old tree in Norway. The pines are of two kinds only - the Furu, our pine, Pinus silvestris; and the Gran, our fir, Pinus abies.

Wolves seldom appear except in winter, when those who travel in sledges are often pursued by them. Then hunger makes them so bold that they will often snatch a dog from between the knees of a driver.

From the station of Dombaas (where there is a telegraph station and a shop of old silver) we turned aside down the Romsdal, which soon became beautiful, as the road wound above the chrysoprase river Rauma, broken by many rocky islets and swirling into many waterfalls, but always equally radiant, equally transparent, till its colour is washed out by the melting snow in a ghastly narrow valley, which we called the Valley of Death.

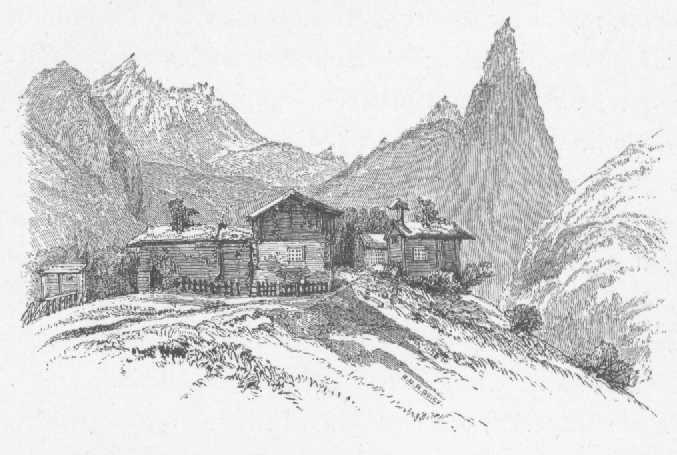

The little inn at Aak, in Romsdal, with a large garden stretching along the hillside, disappointed us at first, as the clouds hid the mountain tops, but morning revealed how glorious they are - purple pinnacles of rock or pathless fields of snow embossed upon a sky which is delicately blue above but melts into the clearest opal. Grander, we thought, than any single peak in Switzerland is the tremendous peak of the Romsdalhorn, and the walks in all directions are most exquisite - into deep glades filled with columbines and the giant larkspurs, which are such a feature of Norway: into tremendous mountain gorges: or to Waeblungsnaes, along the banks of the lovely fyord, with its marvellously quaint forms of mountain distance. Aak is a place whore a month may be spent most delightfully, as well as most comfortably and economically.

IN THE ROMSDAL, NORWAY.

We had heard a great deal before we went to Norway about the difficulty of getting proper food, but our own experience is that we were never fed more luxuriously. Perhaps very late in the season the provisions at the country 'stations' may be some what used up, but when we were there in July only those who could not live without a great deal of meat could have any cause for complaint, and once a week we generally had reindeer for a treat. When we arrived in the evenings, we always found an excellent meal prepared - the most delicious coffee, tea, and cream; baskets of bread, rusks, cakes and biscuits of various descriptions; fresh salmon and trout; cloudberries, bilberries, raspberries, mountain strawberries and cream; and for all this about a franc and a half is the payment required.

My companions lingered at Kristiania whilst I paid a visit, which is one of the most delightful recollections of my tour, to a native family near Moss at the mouth of the fyord; then we came back to Denmark, travelling in the same train with the beloved Prince Imperial, who was then in the height of health and happiness, and received at every station with the enthusiastic 'Hochs!' which in Scandinavia supply the place of the English hurrah.