|

|  |

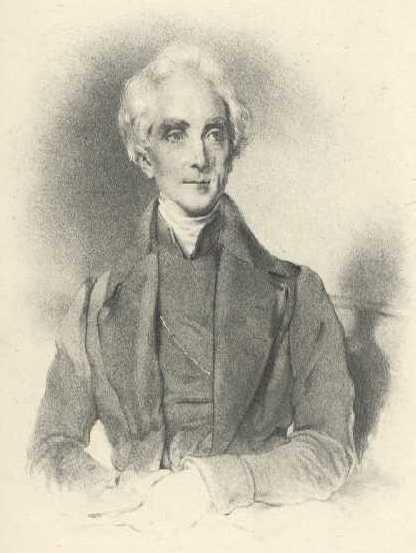

ARTHUR PENRHYN STANLEY

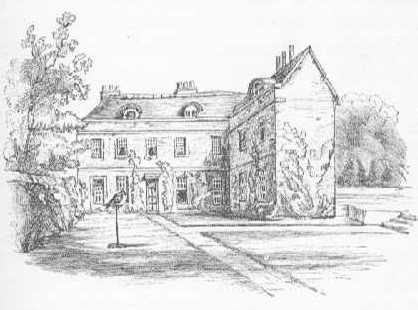

THERE are few country places in England which possess such a singular charm as Alderley. All who have lived in it have loved it, and to the Stanley family it has ever presented the ideal of that which is most interesting and beautiful. There the usually flat pasture-lands of Cheshire rise suddenly into the rocky ridge of Alderley Edge, with its Holy Well under an overhanging cliff, its gnarled pine-trees, and its storm-beaten beacon-tower ready to give notice of an invasion, looking far over the green plain to the smoke of Stockport and Macclesfield, which indicates the presence of great towns on the horizon. Beautiful are the beech-woods which clothe the western side of the Edge, and feather over mossy lawns to the mere, which receives a reflection of their gorgeous autumnal tints, softened by a blue haze on its still waters.

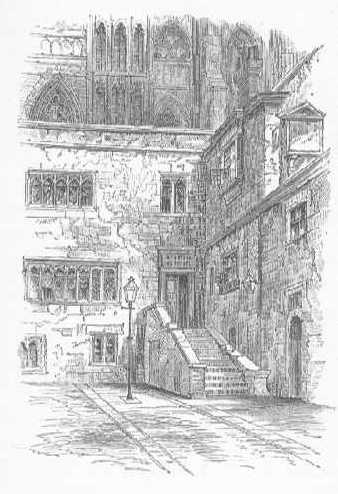

Beyond the mere and Lord Stanley's park, on the edge of the pasture-lands, are the church and its surroundings - a wonderfully harmonious group, encircled by trees, with the old timbered inn of the "Eagle and Child" at the corner of the lane which turns up to them. In later times the church itself has undergone a certain amount of "restoration," but sixty years ago it was marvellously picturesque, its chancel mantled in ivy of massy folds, which, while they concealed the rather indifferent architecture, had a glory of their own very different from that of the clipped, ill-used ivy which we generally see on such buildings; but the old clock-tower, the outside stone staircase leading to the Park pew, the crowded groups of large square, lichen-stained gravestones, the disused font in the churchyard overhung by a yew-tree, and the gable-ended schoolhouse at the gate, built of red sandstone, with grey copings and mullioned windows, were the same.

Close by was the rectory, with its garden - the "Dutch Garden," of many labyrinthine flower-beds - joining the churchyard. A low house, with a verandah, forming a wide balcony for the upper story, where bird-cages hung amongst the roses; its rooms and passages filled with pictures, books, and the old carved oak furniture, usually little sought after or valued in those days, but which the Rector delighted to pick up amongst his cottages.

This Rector, Edward Stanley, younger brother of the Sir John who was living at the Park, was a little man, active in figure and in movement, with dark, piercing eyes, rendered more remarkable by the snow-white hair which was characteristic of him even when very young. With the liveliest interest on all subjects-political, philosophical, scientific, theological with inexhaustible plans for the good of the human race in general, but especially for the benefit of his parishioners and the amusement of his seven nieces at the Park, he was the most popular character in the countryside. To children he was indescribably delightful. There was nothing that he was not supposed to know - and indeed who was there who knew more than he of insect life, of the ways and habits of birds, of fossils and where to find them, of drawing, of etching on wood and lithographing on stone, of plants and gardens, of the construction of ships and boats, and of the thousand home manufactures of which he was a complete master?

In his thirty-first year Edward Stanley had married Catherine, eldest daughter of Oswald Leycester, afterwards Rector of Stoke-upon-Terne, of an old Cheshire family, which, through many generations, had been linked with that of the Stanleys in the intimacy of friendship and neighbourhood; for Toft, the old seat of the Leycesters and the pleasantest of family homes, was only a few miles from Alderley.

At the time of her engagement, Catherine Leycester was only sixteen, and at the time of her marriage only eighteen, but from childhood she had been accustomed to form her own character by thinking, reading, and digesting what she read. Owing to her mother's ill-health, she had very early in life had the responsibility of educating and training her sister, who was much younger than herself. She was the best of listeners, fixing her eyes upon the speaker, but saying little herself, so that her old uncle, Hugh Leycester, used to assert of her, "Kitty has much sterling gold, but gives no ready change." To the frivolity of an ordinary acquaintance, her mental superiority and absolute self-possession of manner must always have made her somewhat alarming; but those who had the opportunity of penetrating beneath the surface were no less astonished at her originality and freshness of ideas, and her keen, though quiet, enjoyment of life, its pursuits and friendships, than by the calm wisdom of her advice, and her power of penetration into the characters, and consequently the temptations and difficulties, of others.

ALDERLEY RECTORY AND CHURCH.

In the happy home of Alderley Rectory her five children were brought up. Her eldest son, Owen, had from the first shown that interest in all things relating to ships and naval affairs which had been his father's natural inclination in early life; and the youngest, Charles, from an early age had turned his hopes to the profession of a Royal Engineer, in which he afterwards became distinguished. Arthur, the second boy, born December 13, 1815, and named after the Duke of Wellington, was always delicate, so delicate that it was scarcely hoped at first he would live to grow up. From his earliest childhood, his passion for poetry, and historical studies of every kind, gave promise of a literary career, and engaged his mother's unwearied interest in the formation of his mind and character. A pleasant glimpse of the home life at Alderley in May, 1818, is given in a letter from Mrs. Stanley to her sister, Maria Leycester: -

"How I have enjoyed these fine days, - and one's pleasure is doubled, or rather I should say trebled, in the enjoyment of the three little children basking in the sunshine on the lawns and picking up daisies and finding new flowers every day, - and in seeing Arthur expand like one of the flowers in the fine weather. Owen trots away to school at nine o'clock every morning, with his Latin grammar under his arm, leaving Mary with a strict charge to unfurl his flag, which he leaves carefully furled, through the little gothic gate, as soon as the clock strikes twelve. So Mary unfurls the flag and then watches till Owen comes in sight, and as soon as he spies her signal he sets off full gallop towards it, and Mary creeps through the gate to meet him, and then comes with as much joy to announce Owen's being come back, as if he was returned from the North Pole. Meanwhile I am sitting with the doors open into the trellis, so that I can see and hear all that passes."

In the same year, after an absence, Mrs. Stanley wrote: -

"Alderley, Sept. 14, 1818. - What happy work it was getting home! The little things were as happy to see us as we could desire. They all came dancing out, and clung round me, and kissed me by turns, and were certainly more delighted than they had ever been before to see us again. They had not only not forgot us, but not forgot a bit about us. Everything that we had done and said and written was quite fresh and present to their minds; and I should be assured in vain that all my trouble in writing to them was thrown away. Arthur is grown so interesting, and so entertaining too, - he talks incessantly, runs about and amuses himself and is full of pretty speeches, repartees, and intelligence: the dear little creature would not leave me, or stir without holding my hand, and he knew all that had been going on quite as much as the others. He is more like Owen than ever, only softer, more affectionate, and not what you call 'so fine a boy.'"

When he was four years old, we find his mother writing to her sister: -

"January 30, 1820. - As for the children, my Arthur is sweeter than ever. His drawing fever goes on, and his passion for pictures and birds, and he will talk sentiment to Mademoiselle about le printemps, les oiseaux, and les fleurs, when he walks out. When he went to Highlake, he asked - quite gravely - whether it would not be good for his little wooden horse to have some sea-bathing!"

And again, in the following summer: -

"Alderley, July 6, 1820. - I have been taking a domestic walk with the three children and the pony to Owen's favourite cavern, Mary and Arthur taking it in turns to ride. Arthur was sorely puzzled between his fear and his curiosity. Owen and Mary, full of adventurous spirit, went with Mademoiselle to explore. Arthur stayed with me and the pony, but when I said I would go, he said, colouring, he would go, he thought: 'But, Mamma, do you think there are any wild dogs in the cavern?' Then we picked up various specimens of cobalt, &c., and we carried them in a basket, and we called at Mrs. Barber's, and we got some string, and we tied the basket to the pony with some trouble, and we got home very safe, and I finished the delights of the evening by reading 'Paul and Virginia' to Owen and Mary, with which they were much delighted, and so was I.

"You would have given a good deal for a peep at Arthur this evening, making hay with all his little strength - such a beautiful colour, and such soft animation in his blue eyes."

It was often remarked that Mrs. Stanley's children were different from those of any one else; but this was not to be wondered at. Their mother not only taught them their lessons, she learnt all their lessons with them. Whilst other children were plodding through dull histories of disconnected countries and ages, of which they were unutterably weary at the time, and of which they remembered nothing afterwards, Mrs. Stanley's system was to take a particular era, and, upon the basis of its general history, to pick out for her children from different books, whether memoirs, chronicles, or poetry, all that bore upon it, making it at once an interesting study to herself and them, and talking it over with them in a way which encouraged them to form their own opinion upon it, to have theories as to how such-and-such evils might have been forestalled or amended, and so to fix it in their recollection.

To an imaginative child, Alderley was the most delightful place possible, and whilst Owen Stanley delighted in the clear brook which dashes through the Rectory garden for the ships of his own manufacture - then as engrossing as the fitting out of the Ariel upon the mere in later boyhood - little Arthur revelled in the legends of the neighbourhood - of its wizard of Alderley Edge, with a hundred horses sleeping in an enchanted cavern, and of the church-bell which fell down a steep hill into Rostherne Mere, and which is tolled by a mermaid when any member of a great neighbouring family is going to die.

Being the poet of the little family, Arthur Stanley generally put his ideas into verse, and there are lines of his written at eleven years old, on seeing the sunrise from the top of Alderley church-tower, and at twelve years old, on witnessing the departure of the Ganges, bearing his brother Owen from Spithead, which give evidence of poetical power, more fully evinced two years later in his longer poems on "The Druids" and on "The Maniac of Betharam." When he was old enough to go to school, his mother wrote an amusing account of the turn-out of his pockets and desk before leaving home, and the extraordinary collection of crumpled scraps of poetry which were found there. In March 1821 Mrs. Stanley wrote: -

"Arthur is in great spirits, and looks well prepared to do honour to the jacket and trousers preparing for him. He is just now opposite to me, lying on the sofa (his lesson being concluded) reading Miss Edgeworth's 'Frank' to himself most eagerly. I must tell you his moral deductions from 'Frank.' The other day, as I was dressing, Arthur, Charlie, and Elizabeth were playing in the passage. I heard a great crash, which turned out to be Arthur running very fast, not stopping himself in time, and coming against the window at the end of the passage, so as to break three panes. He was not hurt, but I heard Elizabeth remonstrating with him on the crime of breaking windows, to which he answered with great sang-froid, 'Yes, but you know Frank's mother said she would rather have all the windows in the house broke than that Frank should tell a lie: so now I can go and tell Mamma, and then I shall be like Frank.' I did not make my appearance, so when the door opened for the entrée after dinner, Arthur came in first in something of a bustle, with cheeks as red as fire, and eyes looking - as his eyes do look - saying the instant the door opened, 'Mamma! I have broke three panes of glass in the passage window: - and I tell you now 'cause I was afraid to forget.' I am not sure whether there is not a very inadequate idea left on his mind as to the sin of glass-breaking, and that he rather thought it a fine thing having the opportunity of coming to tell Mamma something like Frank; however, there was some little effort, vide the agitation and red cheeks, so we must not be hypercritical."

After he was eight years old, Mrs. Stanley, who knew the interest and capacity of her little Arthur about everything, was much troubled by his becoming so increasingly shy, that he never would speak if he could help it, even when he was alone with her, and she dreaded that the companionship of other boys at school, instead of drawing him out, would only make him shut himself up more within himself. Still, in the frequent visits which his parents paid to the seaside at Highlake, he always recovered his lost liveliness of manner and movement, climbed merrily up the sandhills, and was never tired in mind or body. It was therefore a special source of rejoicing when it was found that Mr. Rawson the Vicar of Seaforth (a place five miles from Liverpool, and only half a mile from the sea), had a school for nine little boys, and thither in 1824 it was decided that Arthur should be sent. In August his young aunt wrote: -

"Arthur liked the idea of going to school, as making him approach nearer to Owen. We took him last Sunday evening from Crosby, and he kept up very well till we were to part, but when he was to separate from us to join his new companions, he clung to us in a piteous manner and burst into tears. Mr. Rawson very good-naturedly offered to walk with us a little way, and walk back with Arthur, which he liked better, and he returned with Mr. R. very manfully. On Monday evening we went to have a look at him before leaving the neighbourhood, and found the little fellow as happy as possible, much amused with the novelty of the situation, and talking of the boys' proceedings with as much importance as if he had been there for months He wished us good-bye in a very firm tone, and we have heard since from his Uncle Penrhyn that he had been spending some hours with him, in which he laughed and talked incessantly of all that he did at school. He is very proud of being called 'Stanley,' and seems to like it altogether very much. The satisfaction to Mamma and Auntie is not to be told of having disposed of this little sylph in so excellent a manner. Every medical man has always said that a few years of constant sea-air would make him quite strong, and to find this united to so desirable a master as Mr. R., and so careful and kind a protectress as Mrs. R., is being very fortunate.”

In the following summer the same pen writes from Alderley to one of the family: -

"July 1825. - You know how dearly I love all these children and it has been such a pleasure to see them all so happy together - Owen, the hero upon whom all their little eyes were fixed, and the delicate Arthur able to take his own share of boyish amusements with them, and telling out his little store of literary wonders to Charlie and Catherine. School has not transformed him into a rough boy yet He is a little less shy but not much. He brought back from school a beautiful prize-book for history, of which he is not a little proud; and Mr Rawson has told several people, unconnected with the Stanleys that he never had a more amiable, attentive, or clever boy than Arthur Stanley, and that he never has had to find fault with him since he came. My sister finds, in examining him, that he not only knows what he has learnt himself; but that he picks up all the knowledge gained by the other boys in their lessons, and can tell what each boy in the school has read, &c. His delight in reading 'Madoc' and 'Thalaba' is excessive."

In the following year Miss Leycester writes: -

"Stoke, August 26, 1826. - My Alderley children are more interesting than ever. Arthur is giving Mary quite a literary taste, and is of the greatest advantage to her possible, for they are now quite inseparable companions, reading, drawing, and writing together. Arthur has written a poem on the life of a peacock-butterfly in the Spenserian stanza, with all the old words, with references to Chaucer, &c., at the bottom of the page! To be sure, it would be singular if they were not different from other children, with the advantages they have where education is made so interesting and amusing as it is to them. . . . I never saw anything equal to Arthur's memory and quickness in picking up knowledge; seeming to have just the sort of intuitive sense of everything relating to books that Owen had in ships, - and then there is such affection and sweetness of disposition in him. . . . You will not be tired of all this detail of those so near my heart. It is always such a pleasure to me to write of the Rectory, and I can always do it better when I am away from it and it rises before my mental vision."

ALDERLEY MERE.

The summer of 1826 was marked for the Stanleys by the news of the death of their beloved friend Reginald Heber, and by the marriage of Isabella Stanley to Captain Parry, the Arctic voyager, an event at which his mother "could not resist sending for her little Arthur to be present." Meantime he was happy at school, and wrote long histories home of all that took place there, especially amused with his drilling sergeant, who told him to "put on a bold, swaggering air, and not to look sheepish.” But each time of his return to Alderley he seemed shier than ever, and his mother became increasingly concerned at his want of boyishness. His cousin Emma Tatton, afterwards Lady Mainwaring, recollected how, when a large party of children were playing together, she said, "Now, Arthur, you must come and play at trap and ball." - "But I can't, Cousin Emma," the boy answered, hanging down his hands and head. " But you must." - "No, Cousin Emma, I really can't." - "Well then, Arthur, I'll tell you what, I'll let you off, if you'll go at once and write me an ode to a Snowdrop and give it to me to-morrow morning at breakfast;" and the next morning it was ready. Here is a paraphase of Psalm cxxxix. which he wrote at twelve years old (1827): -

“If up to heav'n I wing my flight,

And seek the realms of endless light,

There Thy eternal glories shine,

And all is holy, all divine,

All free from sin, and pain, and care,

For, full of mercy, Thou art there!

If I descend to deepest hell,

Where evil souls for ever dwell

And bitterly lament their woe,

While torturing fires for ever glow,

Thy dreadful vengeance there I fear,

For Thou, O mighty Lord, art there!

If through the ocean's path I stray,

And o'er its surface urge my way,

If blows the wind, if mounts the wave,

Thy strong right hand can always save,

Though many storms obscure the air,

For, wrapt in tempests, Thou art there!

If, wand'ring from my native home,

To earth's remotest verge I come,

Where everlasting winter reigns

And binds the seas in icy chains,

Or where the sun-scorched deserts glare,

In heat or cold, Thou, Lord, art there!

Whether the rosy morning rise

With radiance on the gladdened skies,

Or noon shed forth his burning ray,

Or evening bring the close of day,

Thy glories through the world appear,

For Thou, O gracious Lord, art there!

In vain amid the darkest night

I would escape Thy piercing sight:

Thou through the deepest shade can'st see,

And darkness is as light to Thee,

E'en as the brightest noontide glare,

For Thou, omniscient God, art there!

Where from Thy presence shall I fly?

Where hide from Thy all-searching eye?

My deeds are still before Thy face,

Thy goodness is in every place:

Thy bounteous grace is ever near,

For Thou, O Lord, art everywhere!"

We find Mrs. Stanley writing: -

"January 27, 1828. - Oh, it is so difficult to know how to manage Arthur. He takes having to learn dancing so terribly to heart, and enacts Prince Pitiful; and will, I am afraid, do no good at it. Then he thinks I do not like his reading because I try to draw him also to other things, and so he reads by stealth, and lays down his book when he hears people coming; and having no other pursuits or anything he cares for but reading, has a listless look, and I am sure he is very often unhappy. I suspect, however, that this is Arthur's worst time, and that he will be a happier man than boy."

In January 1828 Mrs. Stanley wrote to Augustus W. Hare, long an intimate friend of the family, and soon about to marry her sister: -

"I have Arthur at home, and I have rather a puzzling card to play with him - how not to encourage too much his poetical tastes, and to spoil him, in short - and yet how not to discourage what in reality one wishes to grow, and what he, being timid and shy to a degree, would easily be led to shut up entirely to himself; and then he suffers so much from a laudable desire to be with other boys, and yet, when with them, finds his incapacity to enter into their pleasures of shooting, hunting, horses, and take theirs for his. He will be happier as a man, as literary men are more within reach than literary boys."

In the following month she wrote: -

"Alderley, February 8, 1828. - Now I am going to ask your opinion and advice, and perhaps your assistance, on my own account. We are beginning to consider what is to be done with Arthur, and it will be time for him to be moved from his small school in another year, when he will be thirteen. We have given up all thoughts of Eton for him from the many objections, combined with the great expense. Now I want to ask your opinion about Shrewsbury, Rugby, and Winchester; do you think, from what you know of Arthur's character and capabilities, that Winchester would suit him, and vice versâ?"

In answer to this Augustus Hare wrote to her from Naples: -

"March 26, 1828. - Are you aware that the person of all others fitted to get on with boys is just elected master of Rugby? His name is Arnold. He is a Wykehamist and Fellow of Oriel, and a particular friend of mine - a man calculated beyond all others to engraft modern scholarship and modern improvements on the old-fashioned stem of a public education. Winchester under him would be the best school in Europe; what Rugby may turn out I cannot say, for I know not the materials he has there to work on."

A few weeks later he added: -

"Florence, April 19, 1828. - I am so little satisfied with what I said about Arthur in my last letter, that I am determined to begin with him and do him more justice. What you describe him now to be, I once was; and I have myself suffered too much and too often from my inferiority in strength and activity to boys who were superior to me in nothing else, not to feel very deeply for any one in a similar state of school-forwardness and bodily weakness. Parents in general are too anxious to push their children on in school and other learning. If a boy happens not to be robust, it is laying up for him a great deal of pain and mortification. For a boy must naturally associate with others in the same class; and consequently, if he happens to be forward beyond his years, he is thrown at twelve (with perhaps the strength of only eleven or ten) into the company of boys two years older, and probably three or four years stronger (for boobies are always stout of limb). You may conceive what wretchedness this is likely to lead to, in a state of society like a school, where might almost necessarily makes right. But it is not only at school that such things lead to mortification. There are a certain number of manly exercises which every gentleman, at some time or other of his life, is likely to be called on to perform, and many a man who is deficient in these would gladly purchase dexterity in them, if he could, at the price of those mental accomplishments which have cost him in boyhood the most pains to acquire. Who would not rather ride well at twenty-five than write the prettiest Latin verses? I am perfectly impartial in this respect, being able to do neither, and therefore my judgment is likely enough to be correct. So pray during the holidays make Arthur ride hard and shoot often, and, in short, gymnasticise in every possible manner. I have said thus much to relieve my own mind, and convey to you how earnestly I feel on the subject. Otherwise I know Alderley and its inhabitants too well to suspect any one of them of being what Wordsworth calls 'an intellectual all-in-all.' About his school, were Rugby under any other master, I certainly should not advise your thinking of it for Arthur for an instant; as it is, the decision will be more difficult. When Arnold has been there ten years, he will have made it a good school, perhaps in some respects the very best in the island; but a transition state is always one of doubt and delicacy. Winchester is admirable for those it succeeds with, but it is not adapted for all sorts and conditions of boys, and sometimes fails. However, when I come to England, I will make a point of seeing Arthur, when I shall be a little better able perhaps to judge."

In the summer of 1828 Mr. and Mrs. Stanley, with her sister Maria and her niece Lucy Stanley from the Park, went by sea to Bordeaux and for a tour in the Pyrenees, taking little Arthur and his sister Mary with them. It was his first experience of foreign travel, and most intense was his enjoyment of it. All was new then, and Mr. Stanley wrote of the children as being almost as much intoxicated with delight on first landing at Bordeaux as their faithful maid, Sarah Burgess, who "thinks life's fitful dream is past, and that she has, by course of transmigration, passed into a higher sphere." It is recollected how, when he first saw the majestic summit of the Pic du Midi rising above a mass of cloud, Arthur Stanley in his great ecstasy flung himself on the ground exclaiming, "What shall I do! what shall I do!" He described his impressions afterwards in a poem on the Maladetta - one of the many poems he wrote as a child. His father's knowledge of geology had given it such a weird interest that nothing in after-life impressed him more. "It was so awful," he wrote in his journal, "thinking that this mighty Maladetta had burst up out of the earth, driving every other mountain before it; and, as one looked round, seeing them all leaning away from it, as if they shrank in terror from their king."

In the following October Mrs. Stanley described her boy's peculiarities to Dr. Arnold, and asked his candid advice as to how far Rugby was likely to suit him. After receiving his answer she wrote to her sister: -

“October 10, 1828. - Dr. Arnold's letter has decided us about Arthur. I should think there was not another schoolmaster in his Majesty's dominions who would write such a letter. It is so lively, agreeable, and promising in all ways. He is just the man to take a fancy to Arthur, and for Arthur to take a fancy to."

It was exactly as his mother had foreseen. Arthur Stanley went to Rugby in the following January, a bright and eager, but timid and delicate little boy, in a "many-buttoned" blue jacket, frills, and a pink watch-ribbon. He was immediately captivated by his new master. "I should never have taken him for a doctor; he was very pleasant, and does not look old," he wrote to his sister Mary after his first sight of Arnold, who was the man of all others suited to stimulate the best type of English boy. Soon Arthur wrote home that, though he had a great sense of desolation at school, he had "no miseries." Indeed, like many other nervous boys, he was astonished to find that school existence was not very unlike life everywhere else, for, as he wrote afterwards to a school companion, he had looked forward to a long farewell to all goodness and happiness, and wondered how he should ever come out safe."

Two months after Arthur Stanley's entrance at Rugby, his parents visited him as they were returning from Cheshire to London. Mrs. Stanley wrote to her sister: -

"March 1829. - We arrived at Rugby exactly at twelve, waited to see the boys pass, and soon spied Arthur with his books on his shoulder. He coloured up and came in, looking very well, but cried a good deal on seeing us, chiefly I think from nervousness. The only complaint he had to make was that of having no friend, and the feeling of loneliness belonging to that want, and this, considering what he is and what boys of his age usually are, would and must be the case everywhere. We went to dine with Dr. and Mrs. Arnold, and they are of the same opinion, that he was as well off and as happy as he could be at a public school, and on the whole I am satisfied - quite satisfied considering all things, for Dr. and Mrs. Arnold are indeed delightful. She was ill, but still animated and lively. He has a very remarkable countenance, something in forehead, and again in manner, which puts me in mind of Reginald Heber, and there is a mixture of zeal, energy, and determination tempered with wisdom, candour, and benevolence, both in manner and in everything he says. He has examined Arthur's class, and said Arthur has done very well, and the class generally. He said he was gradually reforming, but that it was like pasting down a piece of paper - as fast as one corner was put down another started up. 'Yes,' said Mrs. A., 'but Dr. Arnold always thinks the corner will not start again.' And it is that happy sanguine temperament which is so particularly calculated to do well in this, or indeed any situation."

Soon Arthur Stanley became very happy at Rugby. From the first he had given evidence of his distinctive individuality. He was in his element when he was elected first President of a Debating Society, but it was in vain that once or twice he tried to think he liked playing at football. "Perhaps in time I may like cricket," he wrote to Alderley, where he thought it would give pleasure; but he never did, he always hated it. He hated mathematics and arithmetic too; only one boy, indeed, was ever remembered more utterly hopeless about arithmetic than Arthur Stanley: it was W. F. Gladstone, afterwards Chancellor of the Exchequer! Stanley's physical peculiarities alone made him different from other boys. Through life, the senses of smell and taste were utterly unknown to him; once only - in Switzerland he fancied he smelt the freshness of a pine-wood. "It made the world a paradise," he said.

But though he never understood school ways, Arthur Stanley's school-fellows respected the peculiarities of "the child of light," as Matthew Arnold called him, and left him alone - like a dog of another nature. His study became known as the "Poet's Corner," and from it he was able to announce prize after prize to the home circle, to whom his letters were rapidly becoming one of the most interesting things of life. Want of a friend was speedily supplied at Rugby, and many of the friends of his whole after-life dated from his early school days, especially Charles Vaughan, afterwards his intimate companion, eventually his brother-in-law. His rapid removal into the shell at Easter, and into the fifth form at Midsummer, brought him nearer to the head-master, at the same time freeing him from the terrors of preposters and fagging, and giving him entrance to the library. So he returned to Alderley in the summer holidays well and prosperous, speaking out and full of fun and happiness, ready to enjoy “striding about upon the lawn on stilts'' with his brother and sisters. On his return to school, his mother continued to hear of his progress in learning, but derived even more pleasure from his accounts of football, and of a hare-and-hounds hunt in which he "got left behind with a clumsy boy and a silly one" at a brook, which, after some deliberation, he leapt, and "nothing happened."

In September 1829 his mother writes: -

"I have had such a ridiculous account from Arthur of his sitting up, with three others, all night, to see what it was like! They heartily wished themselves in bed before morning. He also writes of an English copy of verses given to the fifth form - Brownsover, a village near Rugby, with the Avon flowing through it and the Swift flowing into the Avon, into which Wickliffe's ashes were thrown. So Arthur and some others instantly made a pilgrimage to Brownsover to make discoveries. They were allowed four days, and Arthur's was the best of the thirty in the fifth form, greatly to his astonishment, but, he says, 'Nothing happened except that I get called Poet now and then, and my study, Poet's Corner.' The master of the form gave another subject for them to write upon in an hour to see if they had each made their own, and Arthur was again head. What good sense there is in giving subjects of that kind to excite interest and inquiry, though few would be so supremely happy as Arthur in making the voyage of discovery. I ought to mention that Arthur was detected with the other boys in an unlawful letting off of squibs, and had a hundred lines of Horace to translate!"

The following gleanings from his mother's letters give, in the absence of other material, glimpses of Arthur Stanley's life during the next few years

"February 22, 1830. - Arthur writes me word he has begun mathematics, and does not wonder Archimedes never heard the soldiers come in if he was as much puzzled over a problem as he is."

"June 1, 1830. - We got to Rugby at eight, fetched Arthur, to his great delight and surprise, and had two most comfortable hours with him. There is just a shade more of confidence in his manners, which is very becoming. He talked freely and fluently, looked well and happy, and came the next morning at six o'clock with his Greek book and his notebook under his arm."

"June 22, 1830. - There was a letter from Arthur on Monday, saying that his verses on Malta had failed in getting the prize. There had been a hard contest between him and another. His poem was the longest and contained the best ideas, but he says 'that is matter of opinion;' the other was the most accurate. There were three masters on each side, and it was some time in being decided. The letter expresses his disappointment (for he had thought he should have it), his vexation (knowing that another hour would have enabled him to look over, and probably to correct the fatal faults), so naturally, and then the struggle of his amiable feeling that it would be unkind to the other boy, who had been very much disappointed not to get the Essay, to make any excuses. Altogether it is just as I should wish, and much better than if he had got it."

"July 20, 1830. - Arthur came yesterday. He begins to look like a young man."

"December 1830. - Arthur has brought home a letter from Mrs. Arnold to say that she could not resist sending me her congratulations on his having received the remarkable distinction of not being examined at all except in extra subjects. Dr. Arnold called him up before masters and school, and said he had done so perfectly well it was useless."

"December 30, 1830. - I was so amused the other day taking up the memorandum-books of my two boys. Owen's full of calculations, altitudes, astronomical axioms, &c. Arthur's of Greek idioms, Grecian history, parallels of different historical situations. Owen does Arthur a great deal of good by being so much more attentive and civil, it piques him to be more alert. Charlie profits by both brothers. Arthur examines him in his Latin, and Charlie sits with his arm round his neck, looking with the most profound deference in his face for exposition of Virgil."

"February 1831. - Charlie writes word from school: 'I am very miserable, not that I want anything, except to be at home.' Arthur does not mind going half so much. He says he does not know why, but all the boys seem fond of him, and he never gets plagued in any way like the others; his study is left untouched, his things unbroke, his books undisturbed. Charlie is so fond of him, and deservedly so. You would have been so pleased one night, when Charlie all of a sudden burst into violent distress at not having finished his French task for the holidays, by Arthur's judicious good-nature in showing him how to help himself, entirely leaving what he was about of his own employment."

"July 1831. - I am writing in the midst of an academy of art. Just now there are Arthur and Mary drawing and painting at one table; Charlie deep in the study of fishes and hooks, and drawing varieties of both at another; and Catherine with her slate full of houses with thousands of windows. Charlie is fishing mad, and knows how to catch every sort, and just now he informs me that to catch a bream you must go out before breakfast. He is just as fond as ever of Arthur. You would like to see Arthur examine him, which he does so mildly and yet so strictly, explaining everything so à l'Arnold."

"July 17, 1831. - I have been busy teaching Arthur to drive, row, and gymnasticise, and he finds himself making progress in the latter; that he can do more as he goes on - a great encouragement always. Imagine Dr. Arnold and one of the other masters gymnasticising in the garden, and sometimes going out leaping - as much a sign of the times as the Chancellor appearing without a wig, and the king with half a coronation."

"Alderley, November 11. - We slept at Rugby on Monday night, had a comfortable evening with Arthur, and next morning breakfasted with Dr. Arnold. What a man he is! He struck me more than before even with the impression of power - energy, and singleness of heart, aim, and purpose. He was very indignant at the Quarterly Review article on cholera - the surpassing selfishness of it, and spoke so nobly - was busy writing a paper to state what cholera is, and what it is not. . . . Arthur's veneration for him is beautiful; what good it must do to grow up under such a tree."

"December 22, 1831. - I brought Arthur home on Wednesday from Knutsford. He was classed first in everything but composition, in which he was second, and mathematics, in which he did not do well enough to be classed, nor ill enough to prevent his having the reward of the rest of his works. I can trace the improvement from his having been so much under Dr. Arnold's influence; so many inquiries and ideas are started in his mind which will be the groundwork of future study. . . . Charlie is very happy now in the thought of going to Rugby and being with Arthur, and Arthur has settled all the study and room concerns very well for him. I am going to have a sergeant from Macclesfield to drill them these holidays, to Charlie's great delight, and Arthur's patient endurance. The latter wants it much. It is very hard always to be obliged to urge that which is against the grain. I never feel I am doing my duty so well to Arthur as when I am teaching him to dance, and urging him to gymnasticise, when I would so much rather be talking to him of his notebooks, &c. He increasingly needs the free use of his powers of mind too as well as of his body. The embarrassments and difficulty of getting out what he knows seems so painful to him, while some people's pain is all in getting it in; but it is very useful for him to have drawbacks in everything."

"May 22, 1832. - We got such a treat on Friday evening in Arthur's parcel of prizes. One copy he had illustrated in answer to my questions, with all his authorities, to show how he came by the various bits of information. In this parcel he sent 'An Ancient Ballad, showing how Harold the King died at Chester,' the result of a diligent collation of old chronicles he and Mary had made together in the winter. Arthur put all the facts together from memory."

"Dec.26, 1832. - Arthur and Charlie came home on Wednesday. Arthur has not shaken off his first fit of shyness yet. I think he colours more than ever, and hesitates more in bringing out what he has to say. I am at my usual work of teaching him to use his body, and Charlie his mind."

"April 13, 1833. - I never found Arthur more blooming than when we saw him at Rugby on Monday. Mrs. Arnold said she always felt that Arthur had more sympathy with her than any one else, that he understood and appreciated Dr. Arnold's character, and the union of strength and tenderness in it; that Dr. A. said he always felt that Arthur took in his ideas, received all he wished to put into him more in the true spirit and meaning than any boy he had ever met with, and that she always delighted in watching his countenance when Dr. Arnold was preaching."

"July 1833. - At eight o'clock last night the Arnolds arrived. Dr. Arnold and Arthur behind the carriage, Mrs. Arnold and two children inside, two more with the servant in front, having left the other chaiseful at Congleton. Arthur was ddighted with his journey - said Dr. Arnold was just like a boy - jumped up, delighted to be set free - had talked all the way of the geology of the country, knowing every step of it by heart - so pleased to see a common, thinking it might do for the people to expatiate on. We talked of the Cambridge philosophers - why he did not go there - he dared not trust himself with its excitement or with society in London. Edward said something of the humility of finding yourself with people so much your superior, and at the same time the elevation of feeling yourself of the same species. He shook his head - 'I should feel that in the company of legislators, but not of abstract philosophers.' Then Mrs. Arnold went on to say how Deville had pronounced on his head that he was fond of facts, but not of abstractions, and he allowed it was most true; he liked geology, botany, philosophy only as they are connected with the history and well-being of the human race. . . . The other chaise came after breakfast. He ordered all into their places with such a gentle decision, and they were all off by ten, having ascertained, I hope, that it was quite worth while to halt here even for so short a time."

It was in November 1833 that Arthur Stanley went to Oxford to try for the Balliol Scholarship, and gained the first scholarship against thirty competitors. The examination was one especially calculated to show the wide range of Arnold's education. Stanley wrote from Oxford to his family: -

"November 26, 1833. - On Monday our examination began at 10 A.M. and lasted to 4 P.M. - a Latin theme, which, as far as four or five revisals could make sure, was without mistakes, and satisfied me pretty well. In the evening we went in from 7 P.M. till 10, and had a Greek chorus to be translated with notes, and also turned into Latin verses, which I did not do well. On Tuesday from 10 to 1 we had an English theme and a criticism on Virgil, which I did pretty well, and Greek verses from 2 to 4 - middling, and we are to go in again tonight at 9. I cannot the least say if am likely to get it. There seem to he three formidable competitors, especially one from Eton."

"Friday, November 29, 7 1/4 P.M. - I will begin my letter in the midst of my agony of expectation and fear. I finished my examination to-day at two o'clock. At 8 to-night the decision takes place, so that my next three-quarters of an hour will be dreadful. As I do not know how the other schools have done, my hope of success can depend upon nothing, except that I think I have done pretty well, better perhaps from comparing notes than the rest of the Rugby men. Oh, the joy if I do get it! and the disappointment if I do not. And from two of us trying at once, I fear the blow to the school would be dreadful if none of us get it. We had to work the second day as hard as on the first, on the third and fourth not so hard, nor to-day - Horace to turn into English verse, which was good for me; a divinity and mathematical paper, in which I hope my copiousness in the first made up for my scantiness in the second. Last night I dined at Magdalen, which is enough of itself to turn one's head upside down, so very magnificent. . . . I will go on now. We all assembled in the hall and had to wait an hour, the room getting fuller and fuller with Rugby Oxonians crowding in to hear the result. Every time the door opened, my heart jumped, but many times it was nothing. At last the Dean appeared in his white robes and moved up to the head of the table. He began a long preamble - that they were well satisfied with all, and that those who were disappointed were many in comparison with those who were successful, &c. All this time every one was listening with the most intense eagerness, and I almost bit my lips off till - 'The successful candidates are - Mr. Stanley' - I gave a great jump, and there was a half shout amongst the Rugby men. The next was Lonsdale from Eton. The Dean then took me into the chapel, where the Master and all the Fellows were, and there I swore that I would not reveal the secrets, disobey the statutes, or dissipate the wealth of the college. I was then made to kneel on the steps and admitted to the rank of Scholar and Exhibitioner of Balliol College, 'nomine Patris, Fili, et Spiritus.' I then wrote my name, and it was finished. We start to-day in a chaise and four for the glory of it. You may think of my joy; the honour of Rugby is saved, and I am a scholar of Balliol!"

Dr. Arnold wrote to Mrs. Stanley: -

"I do heartily congratulate you, and heartily thank Arthur for the credit and real benefit he has conferred on us. There was a feeling abroad that we could not compete with Eton or the other great schools in the contest for University honours, and I think there was something of this even in the minds of my own pupils, however much they might value my instruction in other respects, and those who wish the school ill for my sake were ready to say that the boys were taught politics, and not taught to be scholars. Already has the effect of Arthur's success been felt here in the encouragement which it has given to others to work hard in the hope of treading in his steps, and in the confidence it has given them in my system. And yet, to say the truth, though I do think that, with God's blessing, I have been useful to your son, yet his success on this occasion is all his own, and a hundred times more gratifying than if it had been gained by my examining. For I have no doubt that he gained his scholarship chiefly by the talent and good sense of his compositions, which are, as you know, very remarkable."

Arthur Stanley remained at Rugby till the following summer, gaining more now, he considered, from Dr. Arnold than at any other time, though his uncle, Augustus Hare, who had been applied to, discouraged his being left at school so long, because, "though most boys learn most during their last year, it is when they are all shooting up together, but Arthur must be left a high tree among shrubs." Of this time are the following letters from Mrs. Stanley: -

"February 3, 1834. - I have just lost Arthur, and a great loss he is to me. The latter part of his time at home is always so much the most agreeable; he gets over his reserve so much more. He has been translating and retranslating Cicero for his improvement, and has been deep in Guizot's Essay on the Civilisation of Europe, besides being chiefly engaged in a grand work, at present a secret, but of which you may perhaps hear more in the course of the spring. I have generally sat with him or he with me, to be ready with criticisms when wanted, and it is delightful to be so immediately and entirely understood - the why and wherefore of an objection seen before it is said. And the mind is so logical, so clear, the taste so pure in all senses, and so accurate. He goes on so quietly and perseveringly as to get through all he intends to get through without the least appearance of bustle or business. He finished his studies at home, I think, with an analysis of the Peninsular battles, trying to understand thereby the pro and con of a battle."

“May 21, 1834. - I have taken the opportunity of spending Sunday at Rugby. Arthur met us two miles on the road, and almost his first words were how disappointed he was that Dr. Arnold had influenza and would not be able to preach! However, I had the compensation of more of his company than under any other circumstances. There were only he and Mrs. Arnold, so that I became more acquainted with both, and altogether it was most interesting. We had the Sunday evening chapter and hymn, and it was very beautiful to see his manner to the little ones, indeed to all. Arthur was quite as happy as I was to have such an uninterrupted bit of Dr. Arnold - he talks more freely to him a great deal than he does at home."

The spring of 1834 had been saddened to the Stanleys by the death of Augustus Hare at Rome; and the decision of his widow - the beloved "Auntie" of Arthur Stanley's childhood - to make Hurstmonceaux her home, led to his being sent, for a few months before going to Oxford, as a pupil to Julius Hare, who was then Rector of Hurstmonceaux. Those who remember the enthusiastic character of Julius Hare, his energy in what he undertook, and his vigorous though lengthy elucidation of what he wished to explain, will imagine how he delighted in re-opening for Arthur Stanley the stores of classical learning which had seemed laid aside for ever in the solitude of his Sussex living. "I cannot speak of the blessing it has been to have Arthur so long with you," his mother wrote afterwards. "He says he feels his mind's horizon so enlarged, and that a foundation is laid of interest and affection for Hurstmonceaux, which he will always henceforward consider as 'one of his homes, one of the many places in the world he has to be happy in.' He writes happily from Oxford, but the lectures and sermons there do not go down after the food he has been living on at Hurstmonceaux and Rugby.”

HURSTMONCEAUX RECTORY.

It may truly be said of Arthur Stanley that he "applied his heart to know, and to search, and to seek out wisdom." During his college life, however, his happiest days were still those rare ones which he was able to spend with the Arnolds at Rugby - his "seventh heaven," whence he wrote of spending a time of the most luxurious happiness he ever had, so unbrokenly delightful.

In this brief sketch one cannot dwell upon his happy and successful career, upon his many prizes, his honours of every kind [1], even upon his Newdigate poem of "The Gipsies," which his father heard him deliver in the Sheldonian Theatre, and burst into tears during the tumult of applause which followed. Well remembered still is the impression produced upon the vast assembly by the beautiful lines in which the Gipsies narrate the cause of their curse: -

"They spake of lovely spots in Eastern lands,

An isle of palms, amid a waste of sands -

Of white tents pitched beside a crystal well,

Where in past days their fathers loved to dwell;

To that sweet islet came at day's decline

A Virgin Mother with her babe Divine;

She asked for shelter from the chill nightbreeze,

She prayed for rest beneath those stately trees;

She asked in vain - what though was blended there

A maiden's meekness with a mother's care;

What though the light of hidden Godhead smiled

In the bright features of that blessed Child?

She asked in vain - they heard, and heeded not,

And rudely drove her from the sheltering spot.

Then fell the voice of judgment from above,

'Who shuts Love out, shall he shut out from Love;

Who drive the houseless wanderer from their door,

Themselves shall wander houseless evermore;

Till He, whom now they spurn, again shall come,

Amid the clouds of heaven, to speak their final doom.'"

The suspicions which were already entertained at Oxford as to Stanley's orthodoxy led to his being warned not to stand for Balliol, but he was warmly welcomed to a fellowship at University.

At Christmas, 1839, he was ordained at St. Mary's, at Oxford, with, amongst others, Richard Church, afterwards Dean of St. Paul's. To the last he was full of mental difficulties as to subscription. "If men subscribed literally to the Articles," he said, "no man in orders, from the Archbishop to the poorest curate on the Cumberland fells, could stay in the Church." He was himself finally decided by a letter from Arnold, who urged that his own difficulties of the same kind had gradually decreased in importance; that he had long been persuaded that subscription to the letter to any amount of human propositions was impossible, and that the door of ordination was never meant to be closed against all but those whose "dull minds and dull consciences" could see no difficulty. Before his ordination he wrote to his friend Vaughan: -

"Alas that a Church with so divine a service should keep its long list of Articles! I am strengthened more and more in my opinion that there is only needed, and only should be, one - 'I believe that Christ is both God and man.'”

Many divines had already been shocked by a characteristic passage which he, then still an undergraduate, had been allowed to add to his father's installation sermon: -

"If the heart of man be full of love and peace, whatsoever be his outward act of division, he is not guilty of schism. Let no man then think himself free from schism because he is in outward conformity with this or any other Church. He is a schismatic, and he only, who creates feuds, scandals, and divisions in the Church of Christ."

It was the preaching part of his clerical duties which Arthur Stanley most dreaded. "He could see his way to twelve sermons, but no more.” His first sermon was preached in Mr. (afterwards Bishop) Pelham's church at Bergapton. Arnold was present. The sermon was for a church building society, and the Rector had felt the subject to be a very safe one. The delivery was terrible. Mr. Somerset Hay was there. As he came out, two old women were walking very wide apart, one on one side of the road, the other on the other, to get out of the way of the carriages, and this made them raise their voices. “Mrs. Maisey," called out one of them, "how be you feeling? I got nothing. I'm very hungry." Stanley's father often spoke to him about his bad delivery.

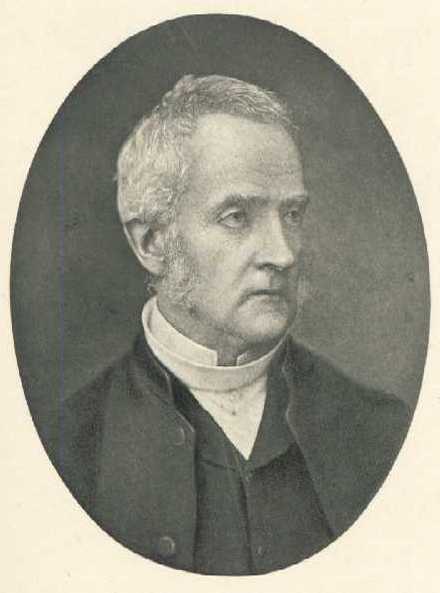

EDWARD STANLEY, BISHOP OF NORWICH.

In deciding to remain at Oxford as a tutor at University College, Stanley believed that his ordination vows might be as effectually carried out by making the most of his vocation at college, and endeavouring to influence all who came within his sphere, as by undertaking any parochial cure. To his aunt, who remonstrated, he wrote: -

"February 15, 1840. - I have never properly thanked you for your letters about my ordination, which I assure you, however, that I have not the less valued, and shall be no less anxious to try, as far as in me lies, to observe. It is perhaps an unfortunate thing for me, though, as far as I see, unavoidable, that the overwhelming considerations, immediately at the time of ordination, were not difliculties of practice, but of subscription, and the effect has been that I would always rather look back to what I felt to be my duty before that cloud came on, than to the time itself. Practically, however, I think it will in the end make no difference. The real thing which long ago moved me to wish to go into orders, and which, had I not gone into orders, I should have acted on as well as I could without orders, was the fact that God seemed to have given me gifts more fitting me for orders, and for that particular line of clerical duty which I have chosen, than for any other. It is perhaps as well to say that until I see a calling to other clerical work, as distinct as that by which I feel called to my present work, I should not think it right to engage in any other; but I hope I shall always feel, though I am afraid I cannot be too constantly reminded, that in whatever work I am engaged now or hereafter, my great end ought always to be the good of the souls of others, and my great support the good which God will give to my own soul.

RUIN IN THE PALACE GARDEN, NORWICH.

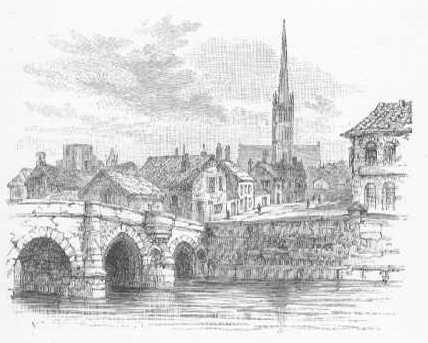

Two years before this, in 1837, the Rector of Alderley had been appointed to the Bishopric of Norwich, and had left Cheshire amidst an uncontrollable outburst of grief from the people amongst whom he had lived as a friend and a father for thirty-two years. Henceforward, the scientific pursuits, which had occupied his leisure hours at Alderley, were laid aside in the no-leisure of his devotion to the See, with whose interests he now identified his existence. His one object seemed to be to fit himself more completely for dealing with ecclesiastical subjects, by gaining a clearer insight into clerical duties and difficulties; and, though he long found his diocese a bed of thorns, his kindly spirit, his broad liberality, and all-embracing fatherly sympathy, never failed to leave peace behind them. His employments were changed, but his characteristics were the same; the geniality and simplicity shown in dealing with his clergy and his candidates for ordination, had the same power of winning hearts which was evinced in his relation to the cottagers at Alderley; and the same dauntless courage which would have been such an advantage in commanding the ship he longed for in his youth, enabled him to face Chartist mobs with Composure, and to read unmoved the many party censures which followed such acts as his public recognition in Norwich Cathedral of the worth of Joseph Gurney, the Quaker philanthropist; his appearance on a platform side by side with the Irish priest Father Mathew, advocating the same cause; and his enthusiastic friendship for Jenny Lind, who on his invitation made the palace her home during her stay in Norwich.

BISHOP'S BRIDGE, NORWICH.

In the early years of his father's episcopate, Arthur Stanley was his father's examining chaplain for ordination candidates. He was then a very juvenile, cherubic-looking youth. The Bishop, with characteristic hospitality, invited all the candidates to dinner. One of them, who was not well prepared, and excessively nervous as to the result of his examination, has often narrated since how he looked round to see his dreaded future examiner. "Can you tell me which is Arthur Stanley?" he said to the bright, ingenuous-looking boy at his side. "Is he here?" And he has never forgotten the shrill voice of the youth as he said, "I am Arthur Stanley." At first he could not believe it; then he was in a most dreadful fright.

THE CHAPEL DOOR, PALACE, NORWICH.

Most delightful, and very different from the modern building which has partially replaced it, was the old Palace at Norwich. Approached through a stately gateway, and surrounded by lawns and flowers, amid which stood a beautiful ruin - the old house with its broad old-fashioned staircase and vaulted kitchen, its beautiful library looking out to Mousehold and Kett's Castle, its great dining-room hung with pictures of the Christian Virtues, its picturesque and curious corners, and its quaint and intricate passages, was indescribably charming. In a little side-garden under the Cathedral, pet pee-wits and a raven were kept, which always came to the dining-room window at breakfast to be fed out of the Bishop's own hand - the only relic of his once beloved ornithological, as occasional happy excursions with a little nephew to Bramerton in search of fossils were the only trace left of his former geological pursuits.

NORWICH FROM MOUSEHOLD.

"I live for my children, and for them alone I wish to live, unless in God's providence I can live to His glory," were Bishop Stanley's own words not many months before his death. He followed with longing interest the voyages of his son Owen as Commander in the Britomart and Captain of the Rattlesnake, and rejoiced in the successful career of his youngest son Charles. These were perhaps the most naturally con'genial to their father, and more of companions to him when at home than any of his other children. But in the last years of his life he was even prouder of his second son Arthur, whose wonderful descriptive power and classical knowledge first became evident to his family in 1840 in his letters from Greece, which gave his intimate circle a foretaste of the interest which the outer world experienced twelve years later in the publication of "Sinai and Palestine." There were not so many travellers' letters then. "A letter from Arthur" caused the whole family to collect in the old-fashioned drawing-room at Stoke Rectory; his aged grandparents were established in their red arm-chairs, and maps were brought out and many books of former travellers consulted, and compared with the accounts in the closely-written sheets, in which a mother's eyes easily conquered all the difficulties of the strange handwriting so often illegible to others.

Arthur Stanley's Greek tour opened a new era in his life. It was a time of limitless enjoy-ment - "the visions of the library at Rugby and of the lecture-room at Balliol constantly blending themselves with the visions of battles, of temples, and oracles." His enchantment came to a climax at Athens - "even more beautiful than Corfu: the long, ivy-leaf shape of the blue mountain range, the silver sea of Salamis, the hills of Pentelicus and Hymettus glowing like hot furnaces in the sun, the columns of the Parthenon and the Olympieium, with their delicate red interwoven with the deep blue sky." In describing these and similar scenes on his return, his whole being glowed and quivered with excitement.

The year 1842 was clouded by Dr. Arnold's death - "the greatest calamity," wrote Arthur Stanley, "that ever has happened to me, almost the greatest that ever can befall me." He hastened to Rugby for the following week, where he preached the funeral sermon, and he left Rugby feeling "as if he had lived years of manifold experience." "I may be thought," he wrote, "to attach an exaggerated importance to what has passed . . . but, if he was not an apostle to others, he was an apostle to me. His sorrow, his reverence, his sympathy, found relief in devoting his best energies to that "Life of Arnold," which has translated his character to the world, and given Arnold a wider influence since his death than he ever attained in his life. Perhaps, of all Stanley's books, Arnold's Life is still the one by which he is best known, and this, in his reverent love for his master, to whom he owed the building up of his mind, is as he would have wished it to be.

For twelve years Arthur Stanley resided at University College as Fellow and Tutor, undertaking also, in the latter part of the time, the laborious duties of secretary to the University Commission, into which he threw himself with characteristic ardour. In 1845 he was appointed Select Preacher to the University, an office resulting in the publication of those "Sermons and Essays on the Apostolic Age," in which he especially endeavoured to exhibit the individual human character of the different apostles.

Very comic are the recollections which Arthur Stanley's pupils retain of his lectures, which, always interesting and original, were delivered in a small voice hardly audible in the lecture-room, while the lecturer's legs were twisted round those of the table in his nervousness. He had not an idea of the usual way of dealing with young men, or what to say to them, least of all how to reprove them. If one of them was hopelessly behind-hand with some exercise, he would meet him, and in his shyest way say, "Good morning, Mr. Smith. I have … not had that essay, you know." Sometimes he would rush out of his rooms to catch the undergraduates, who would emerge from all the corners and passages singing "For he's a jolly good fellow," and would seize some unfortunate Bible-clerk quietly going home to his room, instead of his real prey, and inform him, to his astonishment, that they were going to hold common-room upon him next morning. [2]

He was not discomfited, however, but greatly amused, when an undergraduate told him that the effect of his sermon in chapel the day before had been spoilt by his having a glove on his head the whole time.

Stanley's terribly illegible handwriting often brought him into comical difficulties at Oxford as elsewhere. "Stanley never could be made a bishop, he writes such an abominable hand," said Dean Wellesley. But in printing his books he never found this a disadvantage, as the best readers and compositors were always given to him, while the worst are bestowed on those who write best.

During this time, in which he refused the offer of Alderley Rectory, and (1849) of the Deanery of Carlisle, the recently half-empty college of University became once more crowded with students, drawn thither by his rising fame. His peculiarities did not in the least prevent his being popular. Men soon appreciated one who rejoiced in their triumphs or bewailed their disappointments as if they were his own, and who diffused into his lectures a life and geniality little known at Oxford. Meantime he had rushed, not only with ardour, but with supreme enjoyment, into the religious controversies which were exciting Oxford at the time. The publicity into which suspicions of his unorthodoxy brought his name was never without its attractions. A Church with arms wide enough to embrace almost every form and tenet of belief was already becoming his ideal of what a Christian Church should be.

The year 1849 was marked by the death of Bishop Stanley, which occurred during a visit to Brahan Castle in Scotland. Arthur was with him in his last hours, and brought his mother and sisters back to the desolate Norwich home, where a vast multitude attended the burial of the Bishop in the cathedral. “I can give you the facts," wrote one who was present, "but I can give you no notion of how impressive it was, nor how affecting. There were such sobs and tears from the school-children and from the clergy, who so loved their dear Bishop. A beautiful sunshine lit up everything, shining into the cathedral just at the time. Arthur was quite calm, and looked like an angel with a sister on each side."

From the time of his father's death, from the time when he first took his seat at family prayers in the purple chair where the venerable white head was accustomed to be seen, Arthur Stanley seemed utterly to throw off all the shyness and embarrassment which had formerly oppressed him, to rouse himself by a great effort, and henceforward to forget his own personality altogether in his position and his work. His social and conversational powers, afterwards so great, increased perceptibly from this time.

It was two days after Mrs. Stanley left Norwich that she received the news of the death of her youngest son, Charles, in Van Diemen's Land; and a very few months only elapsed before she learnt that her eldest son, Owen, had only lived to hear of the loss of his father. Henceforward his mother, saddened though not crushed by her triple grief was more than ever Arthur Stanley's care: he made her the sharer of all his thoughts, the confidante of all his difficulties, all that he wrote was read to her before its publication, and her advice was not only sought but taken. In her new home in London, he made her feel that she had still as much to interest her and give a zest to life as in the happiest days at Alderley and Norwich; most of all he pleased her by showing in the publication of the "Memoir of Bishop Stanley," in 1850, his thorough inward appreciation of the father with whom his outward intercourse had been of a less intimate kind than with herself.

CATHERINE STANLEY.

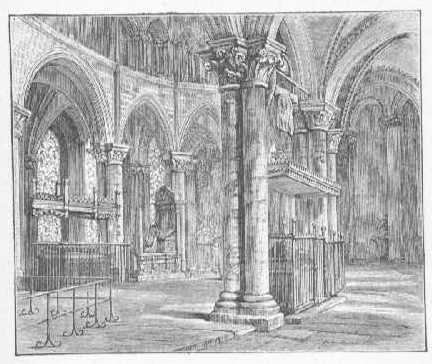

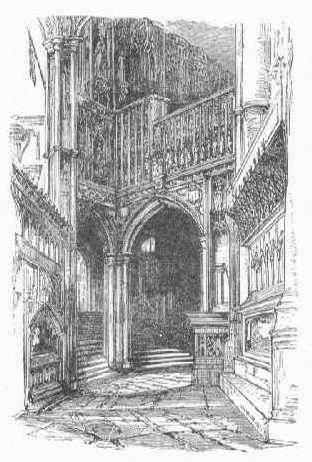

In 1851 Arthur Stanley was presented to a canonry at Canterbury, which, though he accepted it with reluctance, proved to be an appointment entirely after his own heart, giving him leisure to complete his "Commentary on the Corinthians,” a work which, from its deficiency in scholarship, has passed almost unnoticed; and leading naturally to the “Historical Memorials of Canterbury,” which, of all his books was perhaps the one which it gave him most pleasure to write. At Canterbury he not only lived amongst the illustrious dead, but he made them rise into new life by the way in which he spoke and wrote of them. That he endeavoured to teach the cockatoo on its perch by the side of the paved walk leadinmg through the canonry garden to call out “Thomas à Becket" to astonished visitors, was only typical of the way in which he interwove all the other historical recollections of the past with the daily life of the place. Often on the anniversary of Becket's murder, as the fatal hour - five o'clock on a winter's afternoon - drew near, Stanley would marshal his family and friends round the scenes of the event, stopping with thrilling effect at each spot connected with it "Here the knights came into the cloister - here the monks knocked furiously for refuge in the church" - till, when at length the chapel of the martyrdom was reached, as the last shades of twilight gathered amid the arches, the whole scene became so real, that, with almost more than a thrill of horror, one saw the last moments through one's ears - the struggle between Fitzurse and the Archbishop, the blow of Tracy, the solemn dignity of the actual death.

Stanley had a real pride in Canterbury. In his own words, he "rejoiced that he was the servant and minister, not of some obscure fugitive establishment, for which no one cares beyond his narrow circle, but of a cathedral whose name commands respect and interest even in the remotest parts of Europe." In his inaugural lectures as professor at Oxford, in speaking of the august trophies of Ecclesiastical History in England, he said, "I need name but one, the most striking and obvious instance, the cradle of English Christianity, the seat of the English Primacy, my own proud cathedral, the metropolitan church of Canterbury."

CANON STANLEY'S HOUSE, CANTERBURY.

The chief charm to Arthur Stanley of having a home of his own was that he could welcome his mother to it, and greatly did she enjoy her long visits to Canterbury, where she shook off at once all the influences of her London life, and threw herself with all her heart into the interests of the place and its associations. Never were the mother and son more wholly united than in these happy years, when every evening the literary work of the day was read to her, and received her deepest attention, often her severest criticism. It was a delightful time to both, and Mrs. Stanley was one who knew how to make the most of every delicate shade of good in the character of her son and daughters. "Are not one's children given to one," she wrote, "that we may live over again in them when we have done living for ourselves?"

SITE OF BECKET'S SHRINE, CANTERBURY.

Those who remember Stanley's happy intercourse with his mother at Canterbury; his friendships in the place, especially with Archdeacon and Mrs. Harrison, who lived next door, and with whom he had many daily meetings and communications on all subjects; his pleasure in the preparation and publication of his "Canterbury Sermons;" his delightful home under the shadow of the cathedral, connected by the Brick Walk with the cloisters; and his constant work of a most congenial kind, will hardly doubt that in many respects the years spent at Canterbury were the most prosperous of his life. Vividly does the recollection of those who were frequently his guests go back to the afternoons when, his cathedral duties and writing being over, he would rush out to Harbledown, to Patrixbourne, or along the dreary Dover Road (which he always insisted upon thinking most delightful) to visit his friend Mrs. Gregory, going faster and faster as he talked more enthusiastically, calling up fresh topics out of the wealthy past. Or there were longer excursions to Bozendeane Wood, with its memories of the strange story of the so-called Sir William Courtenay, its blood-stained dingle amid the hazels, its trees riddled with shot, and its wide view over the Forest of Blean to the sea, with the Isle of Sheppey breaking the blue waters.

Close behind Stanley's house was the Deanery and its garden, where the venerable Dean Lyall used daily at that time to be seen walking up and down in the sun. Here grew the marvellous old mulberry, to preserve the life of which, when failing, a bullock was actually killed that the tree might drink in new life from its blood. A huge bough which had been torn off from this tree had taken root, and had become far more flourishing than its parent. Arthur Stanley called them the Church of Rome and the Church of England, and gave a lecture about it in the town.

His power of calling up past scenes of history, painting them in words, and throwing his whole heart into them, often enacting them, in some respects made travelling with Arthur Stanley delightful. In the shorter excursions which he made in England, those who were with him vividly recall his intense delight in seeing the tombs of many of his intimate friends of the long ago in the cathedrals. His mother, his sister Mary, his cousin Miss Penrhyn, and his friend Hugh Pearson usually made up the summer party for longer journeys on the Continent. He was a better fellow traveller to this familiar circle, which adored him and only went his way, than to any others He was terribly impatient of being called upon to visit anything he had seen before. He hated all pictures and sculptures which were not historical. He found Dresden "the most uninteresting place he ever saw." He was quite determined never to travel with any one who "went after pictures," and he refused even to attempt acquiring any interest in art. “The difference between others and myself,” he said, "breaks out in the questions we respectively ask. They: - 'Who is the artist?' I: - 'What is the subject?'” The beauties of nature had also lost in his grown-up life all the charm they had for him as a child. The scenery of Switzerland he found utterly "unmeaning," its beauties "fictitious" and dependent on clouds and sunset. In France, Spain, and Germany, a place connected with even the very smallest historic event was attractive to him, but he had no patience with anything else. One thing he did enjoy everywhere. It was tracing an often impossible likeness between the place he was in and some other place. Thus his vivid fancy could imagine that Nüremberg recalled Venice; Rheims, Canterbury; Amalfi, Delphi! For several years the family tours were confined to France and Germany, Switzerland and Northern Italy; but in 1852 the Stanley group went for several months to Italy, seeing its northern and eastern provinces, in those happy days of vetturino travelling, as they will never be seen again studying the story of its old towns, and eventually reaching Rome, which Mrs. Stanley had never seen, and which her son had the greatest delight in showing her. It had been decided that when the rest of the party returned to England, he should go on to Egypt, but this plan was changed by circumstances which fortunately enabled him to witness the funeral of the Duke of Wellington. By travelling day and night, he arrived in London the night before the ceremony. Almost immediately afterwards he returned to take leave of his mother at Avignon, before starting with his friend Theodore Walrond and two others on that long and happy tour of which the results have appeared in "Sinai and Palestine" - rather a poetical and geographical work than a contribution to history, but a book which, without any compromise of its own freedom of thought, has turned all the knowledge of previous travellers to most admirable account. "Stanley was the most wonderful companion in the East," records one of his companions. "He got up his whole subject before, and he particularly liked to tell us everything: it fixed it in his mind. Then in the evenings he would retire to his tent, and write sheets upon sheets of those wonderful letters which only his sister could decipher and translate for other people. He had a whole mass of books with him; one set he took with him up the Nile, and, as he came down, another met him for the Holy Land." [3]

MARY STANLEY

The attention of the family was concentrated on the East in 1854, as Mary Stanley escorted a body of nurses to Constantinople, and took charge of the hospital of Koulalee during the war in the Crimea, gaining much experience at this time which was afterwards useful in her self-denying labours for the poor in London.

As his eight years at Canterbury were the happiest of Arthur Stanley's life, so for himself they were the most profitable. Under the shadow of the great cathedral he had leisure for the literature which was the best work of his life - not only for what he published then, but for the preparation for long distant labours. In "that green oasis,” as he called it, he was removed from, had no calling to, the controversies which marred his afterlife. And he lived in a peace and freedom from abuse which at that time had its value for him: no one cared then that he regarded the Athanasian Creed as only a "curious mediæval hymn."

It was in 1858 that the happy home at Canterbury was exchanged for a canonry at Christ Church, Oxford, attached to the Professorship of Ecclesiastical History, to which Arthur Stanley had been appointed two years before. His professorial appointment had not been welcomed at first, and he used to say that a letter from Jowett was the only letter of congratulation he received upon it. But his three "Introductory Lectures on the Study of Ecclesiastical History," delivered before his residence, had attracted such audiences as have seldom been seen in the University Theatre, and aroused an enthusiasm which was the greatest encouragement to him in entering upon a course of life so different from that he had left; for he saw how a set of lectures usually wearisome could be rendered interesting to all his hearers, how he could make the dry bones live.