I

Antecedents

"Time doth consecrate;

And what is grey with age becomes religion."- Schiller.

"I hope I may be able to tell the truth

always, and to see it aright, according to the eyes which God

Almighty gives me."-Thackeray.

In 1727, the year of George the First's death, Miss Grace

Naylor of Hurstmonceaux, though she was beloved, charming, and

beautiful, died very mysteriously in her twenty-first year, in

the immense and weird old castle of which she had been the

heiress. She was affirmed to have been starved by her former

governess, who lived alone with her, but the fact was never

proved. Her property passed to her first cousin Francis Hare (son

of her aunt Bethaia), who forthwith assumed the name of Naylor.

The new owner of Hurstmonceaux was the only child of the first

marriage of that Francis Hare, who, through the influence first

of the Duke of Marlborough (by whose side, then a chaplain, he

had ridden on the battle-fields of Blenheim and Ramilies), and

afterwards of his family connections the Pelhams and Walpoles,

rose to become one of the richest and most popular pluralists of

his age. Yet he had to be contented at last with the bishoprics

of St. Asaph and Chichester, with each of which he held the

Deanery of St. Paul's, the Archbishopric of Canterbury having

twice just escaped him.

The Bishop's eldest son Francis was "un facheux détail

de notre famille," as the grandfather of Madame de Maintenon

said of his son. He died after a life of the wildest dissipation,

without leaving any children by his wife Carlotta Alston, who was

his stepmother's sister. So the property of Hurstmonceaux went to

his half-brother Robert, son of the Bishop's second marriage with

Mary-Margaret Alston, heiress of the Vatche in Buckinghamshire,

and of several other places besides. Sir Robert Walpole had been

the godfather of Robert Hare-Naylor, and presented him with a

valuable sinecure office as a christening present, and he further

made the Bishop urge the Church as the profession in which father

and godfather could best aid the boy's advancement. Accordingly

Robert took orders, obtained a living, and was made a Canon of

Winchester. While he was still very young, his father had further

secured his fortunes by marrying him to the heiress who lived

nearest to his mother's property of the Vatche, and, by the

beautiful Sarah Selman (daughter of the owner of Chalfont St.

Peter's, and sister of Mrs. Lefevre), he had two sons - Francis

and Robert, and an only daughter Anna Maria, afterwards Mrs.

Bulkeley. In the zenith of her youth and loveliness, however,

Sarah Hare died very suddenly from eating ices when overheated at

a ball, and soon afterwards Robert married a second wife –

the rich Henrietta Henckel, who pulled down Hurstmonceaux Castle.

She did this because she was jealous of the sons of the

predecessor, and wished to build a large new house, which she

persuaded her husband to settle upon her own children, who were

numerous, though only two daughters lived to any great age. But

she was justly punished, for when Robert Hare died, it was

discovered that the great house which Wyatt had built for Mrs.

Hare, and which is now known as Hurstmonceaux Place, was erected

upon entailed land, so that the house stripped of furniture, and

the property shorn of its most valuable farms, passed to Frances

Hare-Naylor, son of Miss Selman. Mrs. Henckel Hare lived on to a

great age, and when "the burden of her years came on her"

she repented of her avarice and injustice, and coming back to

Hurstmonceaux in childish senility, would wander round and round

the castle ruins in the early morning and late evening, wringing

her hands and saying – "Who could have done such a

wicked thing: oh! Who could have done such a wicked thing, as to

pull down this beautiful old place?" Then her daughters,

Caroline and Marianne, walking beside her, would say –"

Oh dear mamma, it was you who did it, it was you yourself who did

it, you know"- and she would despairingly resume –"

Oh no, that is impossible: it could not have been me. I could not

have done such a wicked thing: it could not have been me that did

it." My cousin Marcus Hare had at Abbots Kerswell a picture

of Mrs. Henckel Hare, which was always surrounded with crape bows.

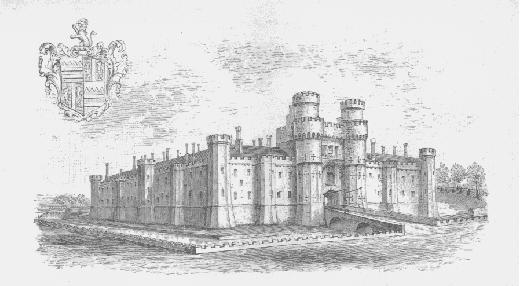

HURSTMONCEAUX CASTLE

The second Francis Hare-Naylor and his brother Robert had a

most unhappy home in their boyhood. Their stepmother ruled their

weak-minded father with a rod of iron. She ostentatiously burnt

the portrait of their beautiful mother. Every year she sold a

farm from his paternal inheritance and spent the money in

extravagance. In 1784 she parted with the ancient property of Hos

Tendis, at Sculthorpe in Norfolk, though its sale was a deathblow

to the Bishop's aged widow, Mary-Margaret Alston. Yet, while

accumulating riches for herself, she prevented her husband from

allowing his unfortunate elder sons more than £100 a year apiece.

With this income, Robert, the younger of the two, was sent to

Oriel College at Oxford, and when he unavoidably incurred debts

there, the money for their repayment was stopped even from his

humble pittance.

Goaded to fury by his stepmother, the eldest son, Francis,

became reckless and recklessly extravagant. He raised money at an

enormous rate of interest upon his prospects from the

Hurstmonceaux estates, and he would have been utterly ruined,

morally as well as outwardly, if he had not fallen in with

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, who was captivated by his good

looks, charmed by his boldness and wit, and who made him the hero

of a living romance. By the Duchess he was introduced to her

cousin, another even more beautiful Georgiana, daughter of

Jonathan Shipley, Bishop of St. Asaph, and his wife Anna Maria

Mordaunt, niece of the famous Earl of Peterborough; and though

Bishop Shipley did everything he could to separate them, meetings

were perpetually connived at by the Duchess, till eventually the

pair eloped in 1785. The families on both sides renounced them

with fury. The Canon of Winchester never saw his son again, and I

believe that Bishop Shipley never saw his daughter. Our

grandparents went to Carlsruhe, and then to Italy, where in those

days it was quite possible to live upon the £200 a year which

was allowed them by the Duchess of Devonshire, and where their

four sons - Francis, Augustus, Julius, and Marcus - were born.

The story of Mrs. Hare-Naylor's struggling life in Italy is

told in " Memorials of a Quiet Life," and how, when the

Canon of Winchester died, and she hurried home with her husband

to take possession of Hurstmonceaux Place, she bought only her

little Augustus with her, placing him under the care of her

eldest sister Anna Maria, widow of the celebrated Sir William

Jones, whom he ever afterwards regarded as a second mother.

The choice of guardians which Mrs. Hare-Naylor made for the

children whom she left at Bologna would be deemed a very strange

one by many: but gifted, beautiful, and accomplished, our

grandmother was never accustomed either to seek or to take advice:

she always acted upon her own impulses, guided by her own

observation. An aged Spanish Jesuit was living in Bologna, who,

when his order was suppressed in Spain, had come to reside in

Italy upon his little pension, and, being skilled in languages,

particularly in Greek, had taken great pains to revive the love

of it in Bologna. Amongst his pupils were two brothers named

Tambroni, one of whom, discouraged by the difficulties he met

with, complained to his sister Clotilda, who, by way of assisting

him, volunteered to learn the same lessons. The old Jesuit was

delighted with the girl, and spared no pains to make her a

proficient. Female professors were not unknown in Bologna, and in

the process of time Clotilda Tambroni succeeded to the chair of

the Professor of Greek, once occupied by the famous Laura Bassi,

whom she was rendered worthy to succeed by her beauty as well as

by her acquirements. The compositions of Clotilda Tambroni both

in Greek and Italian were published, and universally admired; her

poems surprised every one by their fire and genius, and her

public orations were considered unrivalled in her age. Adored by

all, her reputation was always unblemished. When the French

became masters of Bologna, the University was suppressed, and to

avoid insult and danger, Clotilda Tambroni retired into private

life and lived in great seclusion. Some time after, she received

an appointment in Spain, but, just as she arrived there,

accompanied by her monk-preceptor Dom. Emmanuele Aponte, the

French had overturned everything. The pair returned to Bologna,

where Aponte would have been in the greatest distress, if his

grateful pupil had not insisted upon receiving him into her own

house, and not only maintained him, but devoted herself as a

daughter to his wants. After the Austrians had re-established the

University on the old system, Clotilde Tambroni was invited to

resume her chair, but as her health and spirits were then quite

broken, she declined accepting it, upon which the Government very

handsomely settled a small pension upon her, sufficient to ensure

her the comforts of life.

With Clotilde Tambroni and her aged friend, our grandmother

Mrs. Hare-Naylor, who wrote and spoke Greek as perfectly as her

native language, and who taught her children to converse in it at

the family repasts, naturally found more congenial companionship

than with any other members of the Bolognese society; and, when

she was recalled with her husband to England, she had no

hesitation in intrusting three of her sons to their care. Julius

and Marcus were then only very beautiful and engaging little

children, but Francis, my father, was already eleven years old,

and a boy of extraordinary acquirements, in whom an almost

unnatural amount of learning had been implanted and fostered by

his gifted mother. The strange life which he then led at Bologna

with the old monk and the beautiful sibyl (for such she is

represented in her portrait) who attended him, only served to

ripen the seed which had been sown already, and the great

Mezzofanti, who was charmed at seeing a repetition of his own

marvellous powers in one so young, voluntarily took him as a

pupil and devoted much of his time to him. To the year which

Francis Hare passed with Clotilde Tambroni at Bologna, in her

humble rooms with their tiled floors and scanty furniture, he

always felt that he owed that intense love of learning for

learning's sake which was the leading characteristic of his after

life, and he always looked back upon the Tambroni as the person

to whom, next to his mother, he was most deeply indebted. When he

rejoined his parents at Hurstmonceaux, he continued, under his

new tutor, Dr. Lehmann, to make such amazing progress as

astonished all who knew him and was an intense delight to his

mother.

Hurstmonceaux Place was then, and is still, a large but ugly

house. It forms a massy square, with projecting circular bows at

the corners, the appearance of which (due to Wyatt) produces a

frightful effect outside, but is exceedingly comfortable within.

The staircase, the floors, and the handsome doors, were brought

from the castle. The west side of the house, decorated with some

Ionic columns, is part of an older manor-house, which existed

before the castle was dismantled. In this part of the building is

a small old panelled hall, hung round with stags' horns from the

ancient deer-park. The house is surrounded by spacious pleasure-grounds.

Facing the east front were, till a few years ago, three very fine

trees, a cedar, a tulip-tree, and a huge silver fir. In my

childhood it often used to be a question which of these trees

should be removed, as they were crowding and spoiling each other,

and it ended in their all being left, as no one could decide

which was the least valuable of the three. The wind has since

that time carried away the cedar. The tulip-tree was planted by

our great-aunt Marianne, daughter of Mrs. Henckel Hare, and I

remember that my uncle Julius used to say that its gay flowers

were typical of her and her dress.

For several years our grandparents carried on a most laborious

contest of dignity with poverty on their ruined estate of

Hurstmonceaux, where their only daughter Anna Maria Clementina

was born in 1799. Finding no congenial associates in the

neighbourhood, Mrs. Hare-Naylor consoled herself by keeping up an

animated correspondence with all the learned men of Europe, while

her husband wrote dull plays and duller histories, which have all

been published, but which few people read then and nobody reads

now. The long-confirmed habits of Italian life, with its peculiar

hours and utter disregard of appearances, were continued in

Sussex; and it is still remembered at Hurstmonceaux how our

grandmother rode on an ass to drink at the mineral springs which

abound in the park, how she always wore white, and how a

beautiful white doe always accompanied her in her walks, and even

to church, standing, during the service, at her pew door.

Upon the return of Lehmann to Germany in 1802, Francis Hare

was sent to the tutorship of Dr. Brown, and eminent professor in

Marischal College at Aberdeen, where he remained for two years,

working with the utmost enthusiasm. He seems to have shrunk at

this time from any friendships with boys of his own age, except

with Harry Temple (afterwards celebrated as Lord Palmerston), who

had been his earliest acquaintance in England, and with whom he

long continued to be intimate. Meanwhile his mother formed the

design of leaving to her children a perfect series of large

finished water-colour drawings, representing all the different

parts of Hurstmonceaux Castle, interior as well as exterior,

before its destruction. She never relaxed her labour and care

till the whole were finished, but the minute application, for so

long a period, seriously affected her health and produced disease

of the optic nerve, which ended in total blindness. She removed

to Weimar, where the friendship of the Grand Duchess and the

society of Goethe, Schiller, and the other learned men who formed

the brilliantly intellectual circle of the little court did all

that was possible to mitigate her affliction. But her health

continued to fail, and her favourite son Francis was summoned to

her side, arriving in time to accompany her to Lausanne, where

she expired, full of faith, hope, and resignation, on Easter

Sunday, 1806.

After his wife's death, Mr. Hare-Naylor could never bear to

return to Hurstmonceaux, and sold the remnant of his ancestral

estate for £60,000, to the great sorrow of his children. They

were almost more distressed, however, by his second marriage to a

Mrs. Mealey, a left-handed connection of the Shipley family

– the Mrs. Hare-Naylor of my own childhood, who was less and

less liked by her stepsons as years went on. She became the

mother of three children, Georgiana, Gustavus, and Reginald

– my half aunt and uncles. In 1815, Mr. Hare-Naylor died at

Tours, and was buried at Hurstmonceaux.

The breaking up of their home, the loss of their beloved

mother, and still more their father's second marriage, made the

four Hare brothers turn henceforward for all that they sought of

sympathy or affection to their Shipley relations. The house of

their mother's eldest sister, Lady Jones, was henceforward the

only home they knew. Little Anna Hare was adopted by Lady Jones,

and lived entirely with her till her early death in 1813:

Augustus was educated at her expense and passed his holidays at

her house of Worting, her care and anxiety for his welfare

proving that she considered him scarcely less her child than Anna;

and Francis and Julius looked up to her in everything, and

consulted her on all points, finding in her "a second mother,

a monitress wise and loving, both in encouragement and reproof."1

While Augustus was pursuing his education at Winchester and New

College, and Marcus was acting as midshipman and lieutenant in

various ships on foreign service; and while Julius (who already,

during his residence with his mother at Weimar, had imbibed that

passion for Germany and German literature which characterised his

after life) was carrying off prizes at Tunbridge, the Charter

House, and Trinity College, Cambridge; Francis, after his mother's

death, was singularly left to his own devices. Mr. Hare-Naylor

was too apathetic, and his stepmother did not dare to interfere

with him: Lady Jones was bewildered by him. After leaving

Aberdeen he studied vigorously, even furiously, with a Mr.

Michell at Buckland. From time to time he went abroad, travelling

where he pleased and seeing whom he pleased. At the Universities

of Leipsic and Göttingen the report which Lehmann gave of his

extraordinary abilities procured him an enthusiastic reception,

and he soon formed intimacies with the most distinguished

professors of both seats of learning. At the little court of

Weimar he was adored. Yet the vagaries of his character led him

with equal ardour to seek the friendship and share the follies of

Count Calotkin, of whom he wrote as "the Lord Chesterfield

of the time, who had had more princesses in love with him and

perhaps more children on the throne than there are weeks in the

year." At twenty, he had not only all the knowledge, but

more than all the experiences, of most men of forty. Such

training was not a good preparation for his late entrance at an

English University. The pupil of Mezzofanti and Lehmann also went

to Christ Church at Oxford knowing far too much. He was so far

ahead of his companions, and felt such a profound contempt for

the learning of Oxford compared with that to which he had been

accustomed at the Italian and German universities, that he

neglected the Oxford course of study altogether, and did little

except hunt whilst he was at college. In spite of this, he was so

naturally talented, that he could not help adding, in spite of

himself, to his vast store of information. Jackson, Dean of

Christ Church in his time, used to say that "Francis Hare

was the only rolling stone he knew that ever gathered any moss."

That which he did gather was always made the most of for his

favourite brother Julius, for whose instruction he was never

weary of writing essays, and in whose progress he took the

greatest interest and delight. But through all the changes of

life the tie between each of the four brothers continued

undiminished – "the most brotherly of brothers,"

their common friend Landor always used to call them.

After leaving Oxford, my father lived

principally at his rooms in the Albany. Old Dr. Wellesley2

used often to tell me stories of these pleasant chambers (the end

house in the court), and of the parties which used to meet in

them, including all that was most refined and intellectual in the

young life of London. For, in his conversational powers, Francis

Hare had the reputation of being perfectly unrivalled, and it was

thus, not in writing, that his vast amount of information on all

possible subjects became known to his contemporaries. In 1811,

Lady Jones writes of him "at Stowe" as "keeping

all the talk to himself, which does not please the old Marquis

much."

Francis Hare sold his father's fine

library at Christie's soon after his death, yet almost

immediately began to form a new collection of books, which soon

surrounded all the walls of his Albany chambers. But his half-sister

Mrs. Maurice remembered going to visit him at the Albany, and her

surprise at not seeing his books. "Oh, Francis, what have

you done with your library?" she exclaimed. "Look under

the sofa and you will see it," he replied. She looked, and

saw a pile of Sir William Jones's works: he had again sold all

the rest. And through life it was always the same. He never could

resist collecting valuable books, and then either sold them, or

had them packed up, left them behind, and forgot all about them.

Three of his collections of books have been sold within my

remembrance, one at Newbury in July 1858; one at Florence in the

spring of 1859; and one at Sotheby & Wilkinson's rooms in the

following November.

Careful as to his personal appearance,

Francis Hare was always dressed in the height of the fashion. It

is remembered how he would retire and change his dress three

times in the course of a single ball! In everything he followed

the foibles of the day. "Francis leads a rambling life of

pleasure and idleness," wrote his cousin Anna Maria Dashwood;

"he must have read, but who can tell at what time?

– for wherever there is dissipation, there is Francis in its

wake and its most ardent pursuer. Yet, in spite of this, let any

subject be named in society, and Francis will know more of it

than nineteen out of twenty."

In 1816-17, Francis Hare kept horses and

resided much at Melton Mowbray, losing an immense amount of money

there. After this time he lived almost entirely upon the

Continent. Lord Desart, Lord Bristol and Count d'Orsay were his

constant companions and friends, so that it is not to be wondered

at that attractions of the less reputable kind enchained him to

Florence and Rome. He had, however, a really good friend in John

Nicholas Fazakerley, with whom his intimacy was never broken, and

in 1814, whilst watching his dying father at Tours, he began a

friendship with Walter Savage Landor, with whom he ever

afterwards kept up an affectionate correspondence. Other friends

of whom he saw much in the next few years were Lady Oxford (then

separated from her husband, and living entirely abroad) and her

four daughters. In the romantic interference of Lady Oxford in

behalf of Caroline Murat, queen of Naples, and in the

extraordinary adventures of her daughters, my father took the

deepest interest, and he was always ready to help or advise them.

On one occasion, when they arrived suddenly in Florence, he gave

a ball in their honour, the brilliancy of which I have heard

described by the older Florentine residents of my own time. Twice

every week, even in his bachelor days, he was accustomed to give

large dinner-parties, and he then first acquired that character

of hospitality for which he was afterwards famous at Rome and

Pisa. Spa was one of the places which attracted him most at this

period of his life, and he frequently passed part of the summer

there. It was on one of these occasions (1816) that he proceeded

to Holland and visited Amsterdam. " I am delighted and

disgusted with this mercantile capital," he wrote to his

brother Augustus. " Magnificent establishments and penurious

economy - ostentatious generosity and niggardly suspicion -

constitute the centrifugal and centripetal focus of Holland's

mechanism. The rage for roots still continues. The gardener at

the Hortus Medicus showed me an Amaryllis (alas! it does not

flower till October), for which King Lewis paid one thousand

guelders (a guelder is about 2 francs and 2 sous). Here, in the

sanctuary of Calvinism, organs are everywhere introduced –

though the more orthodox, or puerile, discipline of Scotland has

rejected their intrusion. But, in return, the sternness of

republican demeanour refuses the outward token of submission -

even to Almighty power: A Dutchman always remains in church with

his hat unmoved from his head."

The year 1818 was chiefly passed by

Francis Hare in Bavaria, where he became very intimate with the

King and Prince Eugene. The latter gave him the miniature of

himself which I still have at Holmhurst. For the next seven years

he was almost entirely in Italy – chiefly at Florence or

Pisa. Sometimes Lord Dudley was with him, often he lived for

months in the constant society of Count d'Orsay and Lady

Blessington. He was fêted and invited everywhere. "On

disait de M. Hare," said one who knew him intimately, "non

seulement qu'il était original, mais qu'il était original sans

copie." "In these years at Florence," said the

same person, "there were many ladies who were aspirants for

his hand, he was si aimable, pas dans le sens vulgaire, mais

il avait tant d'empressement pour tout la sexe feminin."

His aunts Lady Jones and her sister Louisa Shipley constantly

implored him to return to England and settle thee, but in vain:

he was too much accustomed to a roving life. Occasionally he

wrote for Reviews, but I have never been able to trace the

articles. He had an immense correspondence, and his letters were

very amusing, when their recipients could read his almost

impossible hand. We find Count d'Orsay writing, apropos of a debt

which he was paying – "Employez cette somme à prendre

un maître d'écriture: si vous saviez quel service vous

renderiez à vos amis!"

The English family of which Francis Hare

saw most at Florence was that of Lady Paul, who had brought her

four daughters to spend several years in Italy, partly for the

sake of completing their education, partly to escape with dignity

from the discords of a most uncongenial home. To the close of her

life Frances Eleanor, first wife of Sir John Dean Paul of

Rodborough, was one of those rare individuals who are never seen

without being loved, and who never fail to have a good influence

over those with whom they are thrown in contact. That she was as

attractive as she was good is still shown in a lovely portrait by

Sir Thomas Lawrence. Landor adored her, and rejoiced to bring his

friend Francis Hare into her society. The daughters were clever,

lively and animated; but the mother was the great attraction to

the house.

Defoe says that "people who boast of

their ancestors are like potatoes, in that their best part is in

underground." Still I will explain that Lady Paul was the

daughter of John Simpson of Bradley in the county of Durham, and

his wife Lady Anne Lyon, second daughter of the 8th

Earl of Strathmore, who quartered the royal arms and claimed

royal descent from Robert II. king of Scotland, grandson of the

famous Robert Bruce: the king's youngest daughter Lady Jane

Stuart having married Sir John Lyon, first Baron Kinghorn, and

the king's grand-daughter Elizabeth Graham (through Euphemia

Stuart, Countess of Strathern) having married his son Sir John

Lyon of Glamis. Eight barons and eight earls of Kinghorn and

Strathmore (which title was added 1677) lived in Glamis Castle

before Lady Anne was born. The family history had been of the

most eventful kind. The widow of john, 6th Lord Glamis,

was burnt as a witch on the Castle Hill at Edinburgh, for

attempting to poison King James V., and her second husband,

Archibald Campbell, was dashed to pieces while trying to escape

down the rocks which form the foundation of the castle. Her son,

the 7th Lord Glamis, was spared, and restored to his

honours upon the confession of the accusers of the family that

the whole story was a forgery, after it had already cost the

lives of two innocent persons. John, 8th Lord of

Glamis, was killed in a border fray with the followers of the

Earl of Crawford: John, 5th Earl, fell in rebellion at

the battle of Sheriffmuir: Charles, 6th Earl, was

killed in a quarrel. The haunted castle of Glamis itself, the

most picturesque building in Scotland, girdled with quaint pepper-box

turrets, is full of the most romantic interest. A winding stair

in the thickness of the wall leads to the principal apartments.

The weird chamber is still shown in which, as Shakespeare

narrates, Duncan, king of Scotland, was murdered by Macbeth, the

"thane of Glamis." In the depth of the walls is another

chamber more ghastly still, with a secret, transmitted from the

fourteenth century, which is always known to three persons. When

one of the triumvirate dies, the survivors are compelled by a

terrible oath to elect a successor. Every succeeding Lady

Strathmore, Fatima-like, has spent her time in tapping at the

walls, taking up the boards, and otherwise attempting to discover

the secret chamber, but all have failed. One tradition of the

place says that "Old Beardie"3 sits for ever in that chamber playing with

dice and drinking punch at a stone table, and that at midnight a

second and more terrible person joins him.

GLAMIS CASTLE

More fearful than these traditions were

the scenes through which Lady Anne had lived and in which she

herself bore a share. Nothing is more extraordinary than the

history of her eldest brother's widow, Mary-Eleanor Bowes, 9th

Countess of Strathmore, who, in her second marriage with Mr.

Stoney, underwent sufferings which have scarcely ever been

surpassed, and whose marvellous escapes and adventures are still

the subject of a hundred story-books.

The vicissitudes of her eventful life,

and her own charm and cleverness, combined to make Lady Anne

Simpson one of the most interesting women of her age, and her

society was eagerly sought and appreciated. Both her daughters

had married young, and in her solitude, she took the eldest

daughter of Lady Paul to live with her and brought her up as her

own child. In her house, Anne Paul saw all the most remarkable

Englishmen of the time. She was provided with the best masters,

and in her home life she had generally the companionship of the

daughters of her mother's sister Lady Liddell, afterwards Lady

Ravensworth, infinitely preferring their companionship to that of

her own brothers and sisters. Lady Anne Simpson resided chiefly

at a house belonging to Colonel Jolliffe at Merstham in Surrey,

where the persons she wished to see could frequently come down to

her from London. The royal dukes, sons of George III., constantly

visited her in this way, and delighted in the society of the

pretty old lady, who had so much to tell, and who always told it

in the most interesting way.

It was a severe trial for Anne Paul, when,

in her twentieth year (1821), she lost her grandmother, and had

to return to her father's house. Not only did the blank left by

the affection she had received cause her constant suffering, but

the change from being mistress of a considerable house and

establishment to becoming an insignificant unit in a large party

of brothers and sisters was most disagreeable, and she felt it

bitterly.

Very welcome therefore was the change

when Lady Paul determined to go abroad with her daughters, and

the society of Florence, in which Anne Paul's great musical

talents made her a general favourite, Was the more delightful

from being contrasted with the confinement of Sir John Paul's

house over his bank in the Strand. During her Italian travels

also, Anne Paul made three friends whose intimacy influenced all

her after life. These were our cousin, the clever widowed Anna

Maria Dashwood, daughter of Dean Shipley; Walter Savage Landor;

and Francis Hare; and the two first united in desiring the same

thing - her marriage with the last.

Meantime, two other marriages occupied

the attention of the Paul family. One of Lady Paul's objects in

coming abroad had been the hope of breaking through an attachment

which her third daughter Maria had formed for Charles Bankhead,

an exceedingly handsome and fascinating, but penniless young

attaché, with whom she had

fallen in love at first sight, declaring that nothing should ever

induce her to marry anyone else. Unfortunately, the first place

to which Lady Paul took her daughters was Geneva, and Mr.

Bankhead, finding out where they were, came thither (from

Frankfort, where he was attaché)

dressed in a long cloak and with false hair and beard. In this

disguise, he climbed up and looked into a room where Maria Paul

was writing, with her face towards the window. She recognised him

at once, but thought it was his double and fainted away. On her

recovery, finding her family still inexorable, she one day, when

her mother and sisters were out, tried to make away with herself.

Her room faced the stairs, and as Prince Lardoria, an old friend

of the family, was coming up, she threw open the door and

exclaimed - "Je meurs, Prince, je meurs, je me suis

empoisonné." - "Oh Miladi,

Miladi," screamed the Prince, but Miladi was not there, so

he rushed into the kitchen, and seizing a large bottle of oil,

dashed upstairs with it, and, throwing Maria Paul on the

ground, poured the contents of it down her throat. After this,

Lady Paul looked upon the marriage as inevitable, and sent Maria

to England to her aunt Lady Ravensworth, from whose house she was

married to Charles Bankhead, neither her mother or sisters being

present. Shortly afterwards that Mr. Bankhead was appointed

minister in Mexico and his wife accompanying him thither,

remained there for many years, and had many extraordinary

adventures, especially during a great earthquake, in which she

was saved by her presence of mind in swinging up on the door,

while "the cathedral dropped like a wave on the sea"

and the town was laid in ruins.

While Maria Paul's marriage was pending,

her youngest sister Jane had also become engaged, without the

will of her parents, to Edward, only son of the attainted Lord

Edward Fitz Gerald, son of the first Duke of Leinster. His mother

was that famous Pamela,4 once the beautiful and fascinating little

fairy produced at eight years old by the Chevalier de Grave as

the companion of Mademoiselle d'Orleans; over whose birth a

mystery has always prevailed; whose name Madame de Genlis

declared to be Sims, but whom her royal companions called Seymour.

To her daughter Jane's engagement Lady Paul rather withheld than

refused her consent, and it was hoped that during their travels

abroad the intimacy might be broken off. It had begun by Jane

Paul, in a ball-room, hearing a peculiarly hearty and ringing

laugh from a man she could not see, and in her high spirits

imprudently saying - "I will marry the man who can laugh in

that way and no one else," - a remark which was repeated to

Edward Fitz Gerald, who insisted upon being immediately

introduced. Jane Paul was covered with confusion, but as she was

exceedingly pretty, this only added to her attractions, and the

adventure led to a proposal, and eventually, through the

friendship and intercession of Francis Hare, to a marriage.5

Already, in 1826, we find Count d'Orsay

writing to Francis Hare in August - "Quel diable vous

possede de rester à Florence, sans

Pauls, sans rien enfin, excepté un rhume imaginaire pour

excuse?" But it was not till the following year that Miss

Paul began to believe he was seriously paying court to her. They

had long corresponded, and his clever letters are most

indescribably eccentric. They became more eccentric still in 1828,

when, before making a formal proposal, he expended two sheets in

proving to her how hateful the word must always had been

and always would be to his nature. She evidently accepted this

exordium very amiably, for on receiving her answer, he sent his

banker's book to Sir John Paul, begging him to examine and see if,

after all his extravagancies, he still possessed at least "fifteen

hundred a year, clear of every possible deduction and charge, to

spend withal, that is, four pounds a day," and to

consider, if the examination proved satisfactory, that he begged

to propose for the hand of his eldest daughter! Equally strange

was his announcement of his engagement to his brother Augustus at

Rome, casually observing, in the midst of antiquarian queries

about the temples - "Apropos of columns, I am going to rest

my old age on a column. Anne Paul and I are to be married on the

28th of April," - and proceeding at once, as if he had said

nothing unusual - "Have you made acquaintance yet with my

excellent friend Luigi Vescovali," &c. At the same time

Mrs. Dashwood wrote to Miss Paul that Francis had "too much

feeling in principle to marry without feeling that he could make

the woman who was sincerely attached to him happy," and that

"though he has a great many faults, still, when one

considers the sort of wild education he had, that he has been a

sort of pet pupil of the famous or infamous Lord Bristol, one

feels very certain that he must have a more than uncommonly large

amount of original goodness (not sin, though it is the fashion to

say so much on that head) to save him from having many more."

It was just before the marriage that

"Victoire" (often afterwards mentioned in these volumes)

came to live with Miss Paul. She had lost her parents in

childhood, and had been brought up by her grandmother, who, while

she was still very young, "pour assurer son avenir,"

sent her to England to be with Madame Girardôt, who kept a famous shop for ladies'

dress in Albemarle Street. Three days after her arrival, Lady

Paul came there to ask Madame Girardôt to recommend a maid for

her daughter, who was going to be married, and Victoire was

suggested, but she begged to remain where she was for some weeks,

as she felt so lonely in a strange country, and did not like to

leave the young Frenchwomen with whom she was at work. During

this time Miss Paul often came to see her, and they became great

friends. At last a day was fixed on which Victoire was summoned

to the house "seulement pour voir," and then she first

saw Lady Paul. Miss Paul insisted that when her mother asked

Victoire her age, she should say twenty-two at least, as Lady

Paul objected to her having any maid under twenty-eight. "Therefore,"

said Victoire, "when Miladi asked 'Quelle age avez vous?' j'ai

répondu 'Vingt-deux ans, mais je suis devenu toute rouge, oh

comme je suis devenu rouge' - et Miladi a répondu avec son doux

sourire - 'Ah vous n'avez pas l'habitude des mensonges?' - Oh

comme cà m'a tellement frappé."6

My father

was married to Anne Frances Paul at the church in the Strand on

the 28th of April 1828. "Oh comme il y avait du monde!"

Said Victoire, when she described the ceremony to me. A few days

afterwards a breakfast was given at the Star and Garter at

Richmond, at which all the relations on both sides were present,

Maria Leycester, the future bride of Augustus Hare, being also

amongst the guests.

Soon after,

the newly-married pair left for Holland, where they began the

fine collection of old glass for which Mrs. Hare was afterwards

almost famous, and then to Dresden and Carlsbad. In the autumn

they returned to England, and took a London house - 5 Gloucester

Place, where my sister Caroline was born in 1829. The house was

chiefly furnished by the contents of my father's old rooms at the

Albany.

"Victoire"

has given many notes of my father's character at this time.

"M. Hare était sevère, mais il était juste. Il ne

pardonnait une fois - deux fois, et puis il ne pardonnait plus,

il faudrait s'en aller; il ne voudrait plus de celui qui l'avait

offensé. C'était ainsi avec François, son valet à Gloucester

Place, qui l'accompagnait partout et qui avait tout sous la main.

Un jour M. Hare me priait, avec cette intonation de courtoisie qu'il

avait, que je mettrais son linge dans les tiroirs. 'Mais, très

volontiers, monsieur,' j'ai dit. Il avait beaucoup des choses -

des chemises, des foulards, de tout. Eh bien! quelques jours après

il me dit - 'Il me manque quelques foulards - deux foulards de

cette espèce' - en tirant une de sa poche, parcequ'il faisait

attention à tout. 'Ah, monsiuer,' j'ai dit, 'c'est très

probable, en sortant peut-être dans la ville.' 'Non,' il me dit,

'ce n'est pas ça - je suis volé, et c'est François qui les a

pris, et ça n'est pas la première fois,' ainsi enfin il faut

que je le renvoie." It was not till long after that Victoire

found out that my father had known for years that François had

been robbing him, and yet had retained him in his service. He

said that it was always his plan to weigh the good qualities of

any of his dependants against their defects. If the defects

outweighed the virtues, "il faudrait les renvoyer de suite -

si non, il faudrait les laisser aller." When he was in his

"colère" he never allowed his wife to come near him -

"il avait peur de lui faire aucun mal."

The

christening of Caroline was celebrated with great festivities,

but it was like a fairy story, in that the old aunt Louisa

Shipley, who was expected to make her nephew Francis her heir,

then took an offence - something about being godmother, which was

never quite got over. The poor little babe itself was very pretty

and terrible precocious, and before she was a year old she died

of water on the brain. Victoire, who doated upon her, held her in

her arms for the last four-and-twenty hours, and there she died.

Mrs. Hare was very much blamed for having neglected her child for

society, yet, when she was dead, says Victoire, "Madame Hare

avait tellement chagrin, que Lady paul qui venait tous les jours,

priait M. Hare de l'ammener tout de suite. Nous sommes allés à

Bruxelles, parceque là M. FitzGerald avait une maison, - mais de

là, nous sommes retournés bien vite en Angleterre à cause de

la grossesse de Madame Hare, parceque M. Hare ne voulut pas que

son fils soit né à l'étranger, parcequ'il disait, que, étant

le troisième, il perdrait ses droits de l'héritage.7 C'est selon la

loi anglaise - et c'était vraiment temps, car, de suite en

arrivant à Londres, François naquit."

The family

finally left Gloucester Place and went abroad in consequence of

Lady jones's death. After that they never had a settled home

again. When the household in London was broken up, Victoire was

to have left. She had long been engaged to be married to Félix

Ackermann, who had been a soldier, and was in receipt of a

pension for his services in the Moscow campaign. But, when it

came to the parting, "Monsieur et Madame" would not let

her go, saying that they could not let her travel, until they

could find a family to send her with. "It was an excuse,"

said Victoire, "for I waited two years, and the family was

never found. Then I had to consigner all the things, then

I could not leave Madame - and so it went on for two years more,

till, when the family were at Pisa, Félix insisted that I should

come to a decision. Then M. Hare sent for Félix, who had been

acting as a courier for some time, and begged him to come to

Florence to go with us as a courier to Baden. Félix arrived on

the Jeudi Saint. M. Hare came in soon after (it was in my

little room) and talked to him as if they were old friends. He

brought a bottle of champagne, and poured out glasses for us all,

and faisait clinquer les verres. On the Monday we all left

for Milan, and there I was married to Félix, and, after the

season at Baden, Félix and I were to return to Paris, but when

the time came M. Hare would not let us."

"Wherever,"

said Victoire, "M. Hare était en passage - soit à Florence,

soit à Rome, n'importe où, il faudrait toujours des diners, et

des fêtes, pour recevoir M. Hare, surtout dans les ambassade,

pas seulement dans l'ambassade d'Angleterre, mais dans celles de

France, d'Allemagne, etc. Et quand M. Hare ne voyageait plus, et

qu'il était établi dans quelque ville, il donnait à son tour

des diners à lui."

"Il s'occupait

toujours à lire, - pas des romans, mais des anciens livres, dans

lesquelles il fouillait toujours. Quand nous voyageons c'était

la première chose, et il emporta énormément des livres dans la

voiture avec lui. . . . Quand il y'avait une personne qui lui

avait été recommandée, il fallait toujours lui faire voir tout

ce qu'il avait, soit à Rome, soit à Bologne, - et comme il

savait un peu de tout, son avis était demandé pour la valeur

des tableaux, et n'importe de quoi."

On first

going abroad, my father had taken his wife to make acquaintance

with his old friends Lady Blessington and Count d'Orsay, with

whom they afterwards had frequent meetings. Lady Blessington thus

describes to landor her first impressions of Mrs. Hare :-

"Paris,

Feb. 1829. - Among the partial gleams of sunshine which

have illumined our winter, a fortnight's sojourn which

Francis Hare and his excellent wife made here, is remebered

with most pleasure. She is indeed a treasure - well-informed,

clever, sensible, well-mannered, kind, lady-like, and, above

all, truly feminine; the having chosen such a woman reflects

credit and distinction on our friend, and the community with

her has had a visible effect on him, as, without losing any

of his gaiety, it has become softened down to a more mellow

tone, and he appears not only a more happy man, but more

deserving of happiness than before."

My second

brother, William Robert, was born September 20, 1831, at the

Bagni di Lucca, where the family was spending the summer. Mrs.

Louisa Shipley meanwhile never ceased to urge their return to

England.

"Jan.

25, 1831. - I am glad to hear so good an account of my

two little great-nephews, but I should be still more glad to

see them. I do hope the next may be a girl. If Francis liked

England for the sake of being with old friends, he might live

here very comfortably, but if he will live as those

who can afford to make a show, for one year of parade in

England he must be a banished man for many years. I wish he

would be as 'domestic' at home as he is abroad!"

In the

summer of 1832 all the family went to Baden-Baden, to meet Lady

paul and her daughter Eleanor, Sir John, the FitzGeralds, and the

Bankheads. All the branches of Mrs. Hare's family lived in

different houses, but they met daily for dinner, and were very

merry. Before the autumn, my fahter returned to Italy, to the

Villa Cittadella near Lucca, which was taken for two months for

Mrs. Hare's confinement, and there, on the 9th of October, my

sister was born. She received the names of "Anne Frances

Maria Louisa." "Do you mean your poluvumoV daughter

to rival Venus in all her other qualities as well as in the

multitude of her names? or has your motive been rather to

recommend her to a greater number of patron saints?" wrote

my uncle Julius on hearing of her birth. Just before this, Mrs.

Shelley (widow of the poet and one of her most intimate friends)

had written to Mrs. Hare :-

"Your

accounts of your child (Francis) give me very great pleasure.

Dear little fellow, what an amusement and delight he must be

to you. You do indeed understand a Paradisaical life. Well do

I remeber the dear Lucca baths, where we spent morning and

evening in riding about the country - the most prolific place

in the world for all manner of reptiles. Take care of

yourself, dearest friend. . . . Choose Naples for your winter

residence. Naples, with its climate, its scenery, its opera,

its galleries, its natural and ancient wonders, surpasses

every other place in the world. Go thither, and live on the

Chiaja. Happy one, how I envy you. Percy is in brilliant

health and promises better and better.

"Have

you plenty of storms at dear beautiful Lucca? Almost every

day when I was there, vast white clouds peeped out from above

the hills - rising higher and higher till they overshadowed

us, and spent themselves in rain and tempest: the thunder, re-echoed

again and again by the hills, is indescribably terrific. . .

. Love me, and return to us - Ah! return to us! for it is all

very stupid and unaimiable without you. For are not you -

'That cordial drop Heaven in our

cup had thrown,

To make the nauseous draught of

life go down.'"

After a

pleasant winter at Naples, my father and his family went to pass

the summer of 1833 at Castellamare. "C'était à

Castellamare" (says a note by Madame Victoire) "que

Madame Hare apprit la mort de Lady Paul. Elle était sur le

balcon, quand elle la lut dans le journal. J'étais dans une

partie de la maison très éloignée, mais j'ai entendu un cri si

fort, si aigu, que je suis arrivée de suite, et je trouvais

Madame Hare toute étendue sur la parquet. J'appellais - 'Au

secours, au secours,' et Félix, qui était très fort, prenait

Madame Hare dans ses bras, et l'apportait à mettre sur son lit,

et nous l'avons donné tant des choses, mais elle n'est pas

revenue, et elle restait pendant deux heures en cet état. Quand

M. Hare est entré, il pensait que c'était à cause de sa

grossesse. Il s'est agenouillé tout en pleurs à coté de son

lit. Il demandait si je lui avais donné des lettres. 'Mais, non,

monsieur; je ne l'ai pas donné qu'un journal.' On cherchait

longtemps ce journal, parcequ'elle l'avait laissé tomber du

balcon, mais quand il était trouvé, monsieur s'est aperçu tout

de suite de ce qu'elle avait." The death of Lady paul was

very sudden; her sister Lady Ravensworth forst heard of it when

calling to inquire at the door in the Strand in her carriage.

After expressing her sympathy in the loss of such a mother, Mrs.

Louisa Shipley at this time wrote to Mrs. Hare :-

"I

will now venture to call your attention to the blessings you

possess in your husband and children, and more particularly

to the occupation of your thoughts in the education of the

latter. They are now at an age when it depends on a mother to

lay the foundation of principles which they will carry with

them through life. The responsibility is great, and if you

feel it such, there cannot be a better means of withdrawing

your mind from unavailing sorrow, than the hope of seeing

them beloved and respected, and feeling that your own

watchfulness of their early years, has, by the blessing of

God, caused them to be so. Truth is the cornerstone of all

virtues: never let a child think it can deceive you; they are

cunning little creatures, and reason before they can speak;

secure this, and the chief part of your work is done, and so

ends my sermon."

It was in

the summer of 1833, following upon her mother's death, that a

plan was first arranged by which my aunt Eleanor Paul became an

inmate of my father's household - the kind and excellent aunt

whose devotion in all times of trouble was afterwards such a

blessing to her sister and her children. Neither at first or ever

afterwards was the residence of Eleanor Paul any expense in her

sister's household: quite the contrary, as she had a handsome

allowance fromher father, and afterwards inherited a considerable

fortune from an aunt.

In the

autumn of 1833 my father rented the beautiful Villa Strozzi at

Rome, then standing in large gardens of its own facing the

grounds of the noble old Villa Negroni, which occupied the slope

of the Viminal Hill looking towards the Esquiline. Here on the 13th

of March 1834 I was born - the youngest child of the family, and

a most unwelcome addition to the population of this troublesome

world, as both my father and Mrs. Hare were greatly annoyed at

the birth of another child, and beyond measure disgusted that it

was another son.

1 Epitaph at Hurstmonceaux.

2 Principal of New Inn Hall, and afterwards

Rector of Hurstmonceaux.

3 The 4th Earl of Crawford.

4 In her marriage contract (of 1792) with

Lord Edward Fitz Gerald, Pamela was described as the daughter of

Guillaume de Brixey and Mary Sims, aged nineteen, and born at

Fogo in Newfoundland. In Madame de Genlis's Memoirs, it is said

that one Parker Forth, acting for the Duke of Orleans, found, at

Christ Church in Hampshire, one Nancy Sims, a native of Fogo, and

took her to Paris to live with Madame de Genlis, and teach her

royal pupils English. An Englishman named Sims was certainly

living at Fogo at the end of the last century, and his daughter

Mary sailed for Bristol with an infant of a year old, in a ship

commanded by a Frenchman named Brixey and was never heard of

again.

5 Edward Fox Fitz Gerald died Jan. 25, 1863:

his widow lived afterwards at Heavitree near Exeter, where she

died Nov. 2, 1891.

6 I have dwelt upon the first connection of

Madame Victoire Ackermann with our family, not only because her

name frequently occurs again in these Memoirs, but because they

are indebted to notes left by her for much of their most striking

material. I have never known any person more intellectually

interesting, for the class to which she belonged, that Victoire.

Without the slightest exaggeration, and with unswerving rectitude

of intention, her conversation was always charming and original,

and she possessed the rare art of narration in the utmost

perfection.

7 Francis Hare and his father had both been

born abroad.